My Friend Stops By

I’m expecting my friend to stop by. He’s just back from a long trip and says he has something to show me.

I’m expecting my friend to stop by. He’s just back from a long trip and says he has something to show me.

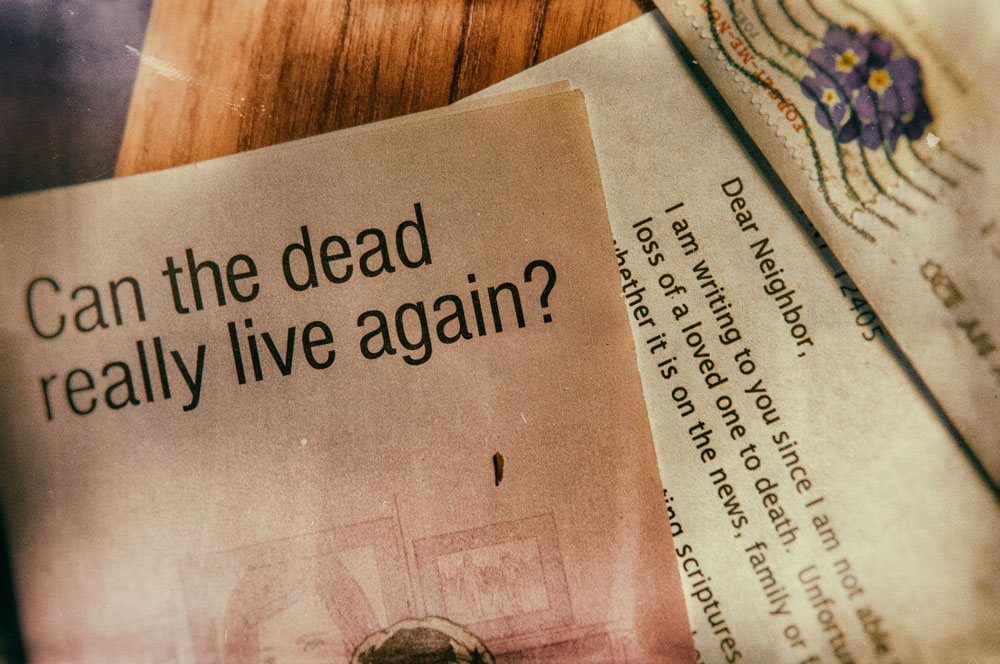

As I’m waiting for him to arrive, I sort through the day’s mail. The usual stuff: credit card applications, AARP cards that I never signed up for, a bill for medical treatment my father received sixteen years ago (a bill long-since paid, my father deceased ten years now), and a letter. A real letter with real handwriting on the envelope! But I don’t recognize the sender’s name and my own is misspelled. I should just toss it away without opening it, but I can’t bring myself to do that. Somebody—a perfect stranger—took the time to write to me and pay the postage. I open the envelope.

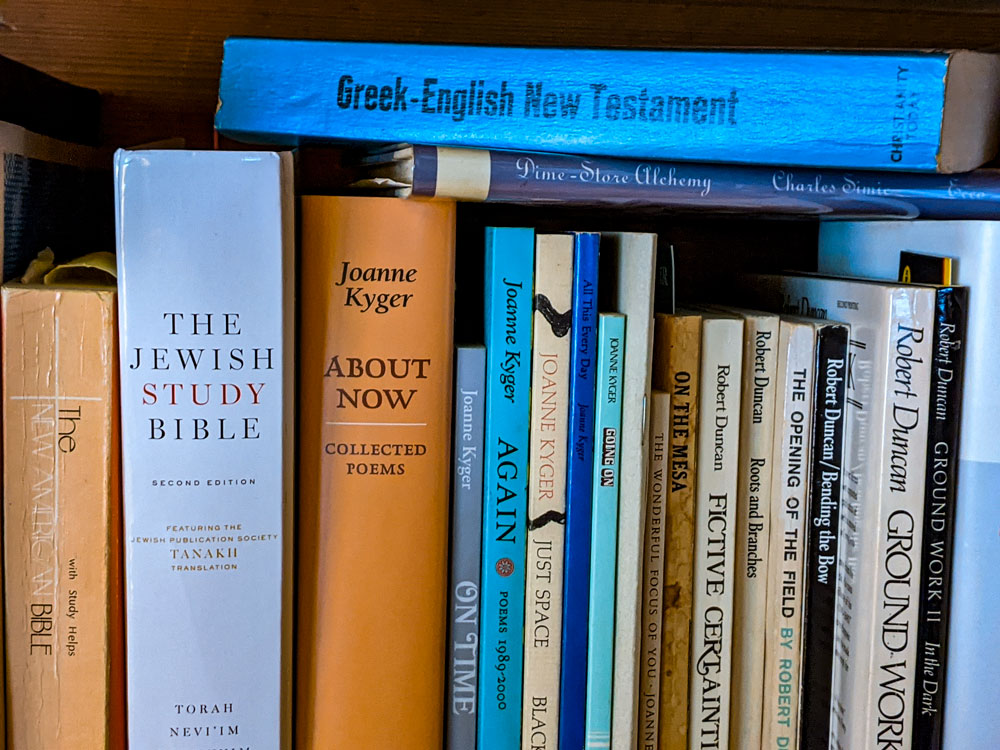

Inside is a typed letter and a little pamphlet. The pamphlet is titled: “Can the dead really live again?” Good question. I glance over at my bookcases, which are crammed with volumes of poetry. Most of the authors are dead, but their words aren’t, not if you read them, especially out loud.

Anyway, back to the letter. It’s addressed to “Dear Neighbor.” That seems a little generic. The return address is several towns north of where I live. Technically, we’re not neighbors, but the neighborly thing to do would be to read it anyway. So I do.

My unknown correspondent begins: “I am writing to you since I am not able to visit you personally.” A vague feeling arises for me, something like relief. I continue reading. “Many of us have experienced the loss of a loved one to death.” There’s an unsettling familiarity of tone here, given I’ve never met this person. Several more sentences follow along the same somber lines. Then comes a Bible quote. I like the Bible. I own several copies of it, in four different languages, including three translations into English. They are lodged where they belong, with the poetry books.

The passage cited by my correspondent is taken from the Book of Job. I like Job. He asks good questions. The quoted passage reads: “He longs to bring back those who are in his memory and to see them live on earth again.” Hmmm, that translation seems a bit of a departure from the ones I’m used to, but what do I know, I don’t read Hebrew. And even if I did, where would it get me? Words do whatever they want inside the heads of those who receive them, no matter how fluent one might be in the language or how much “research” one tries to do in order to get at the “true meaning” of what is being expressed.

I look again at the pamphlet. Curiosity gets the better of me. I open it. Like me, it’s full of questions. “Why study the Bible?” “Can we really believe what the Bible says?” “Why do we grow old and die?” Those are good questions. So are mine. I’ll bet yours are too. A teacher once told me, “Your question is your treasure.” If so, I’m a rich person. Maybe you are too.

On the back of the pamphlet is a coupon to fill out and send in if you want help with your questions. I can use all the help I can get, but I have my doubts. There’s a little box on the coupon you can check if you feel like it. Next to the box are the words: “Please send someone to visit me.” Another vague feeling arises. I can’t put a name on this one. Others might—but I won’t—check the little box. I’ll just sit with my questions as they are. We’ve been together for a long time. There’s a certain communion between us.

Now I hear a car pulling up our drive. It’s my friend. I put the letter and pamphlet aside and go out to greet him. He’s just back from a driving trip to the Midwest. He has a story to tell.

He was visiting an old friend whose recently deceased father had been a professor of literature at a college out there among the cornfields. The son inherited the father’s books—hundreds and hundreds of volumes of poetry, many of them first editions by famous poets from fifty and sixty years ago. Those poets are all gone now. The son is a neurosurgeon and has no use for books of poetry. “What would I do with them?” Yet he can’t bear the thought of disposing of his father’s treasures by consigning them to the shredder or hauling them off to the dump.

He says to his friend, my friend: “You have a need for poetry, don’t you?”

My friend, himself a professor of literature, as I myself once was, says to his friend: “Yes, I do.”

“Then please,” says my friend’s friend, “take some of these books for yourself. Take as many as you want.”

My friend concludes the story by laying a hand on the trunk of his car. Then he says: “Wait till you see what I have in here!”

He pops the lid. The compartment is open. The feeling that arises for me now is like the one I had the moment after my father died.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on February 5, 2021