Living Landscape – A 1997 Interview with Gary Snyder

In October 1997, I interviewed the poet Gary Snyder. The subject of our discussion was the influence the American West and its literature has had on him and on his work. Over the course of his long career, he has published more than two dozen books and has been awarded both the Pulitzer (1975) and the Bollingen (1997) Prizes, but his importance extends well beyond literature. “I wish to be a spokesman,” he has said, “for a realm that is not usually represented either in intellectual chambers or in the chambers of government” (Turtle Island 106). Snyder is one of our culture’s venerable teachers. Since 1986, he has been a professor at the University of California, Davis, where, in addition to conducting classes in writing and literature, he founded that institution’s acclaimed Nature and Culture Program.

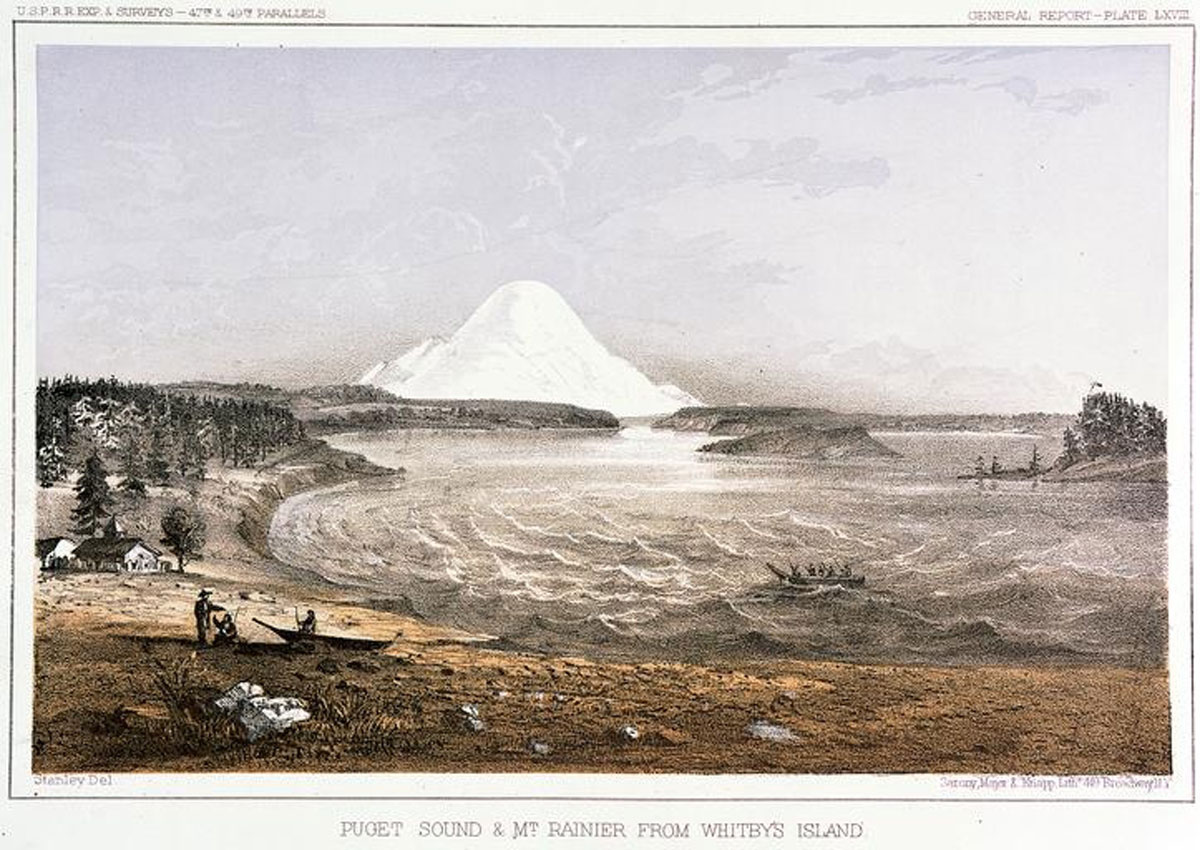

I first met Snyder at Davis in April 1986, during my first year of doctoral studies and his first year on the faculty. To introduce himself to the university community, he gave a reading and talked about the mountains of the West. In particular he spoke of the Cascades, that snowy string of volcanic peaks that extends like a necklace along the Pacific Slope, from northern California to British Columbia. “Those unearthly glowing floating snowy summits are a promise to the spirit,” he later wrote in The Practice of the Wild (117 ). Even when shrouded in clouds, the “Guardian Peaks” of the Columbia–now bearing the names Hood, Adams, and St. Helens, but formerly known as Wy’east, Klickitat, and Loowit–were always visible in his imagination. He came to know his home place intimately by climbing its mountains. He stood on the summit of his first major peak when he was fifteen years old, and from there he could see the next mountain. He resolved to climb it. From the top of that peak, he could see the next. And on it went, one climb leading to another, a life measured in mountains rather than years.

In the library of the Mazamas, a mountaineering organization in Portland, you can browse through the old summit registers, those ledger books that used to sit in heavy aluminum boxes at the top of each peak. Successful climbers would sign in on these pages. It was a record of achievement, as good as pinning your name to a cloud. In the register from Mount St. Helens on August 13, 1945, you will find the bold signature of a fifteen-year-old boy named Gary Snyder, who would one day write a line that, if now applied to this particular vol canic landscape, would seem an understatement: “Streams and mountains never stay the same” (Mountains 143).

______________

JO’G: What do you remember about your first climb of Mount St. Helens?

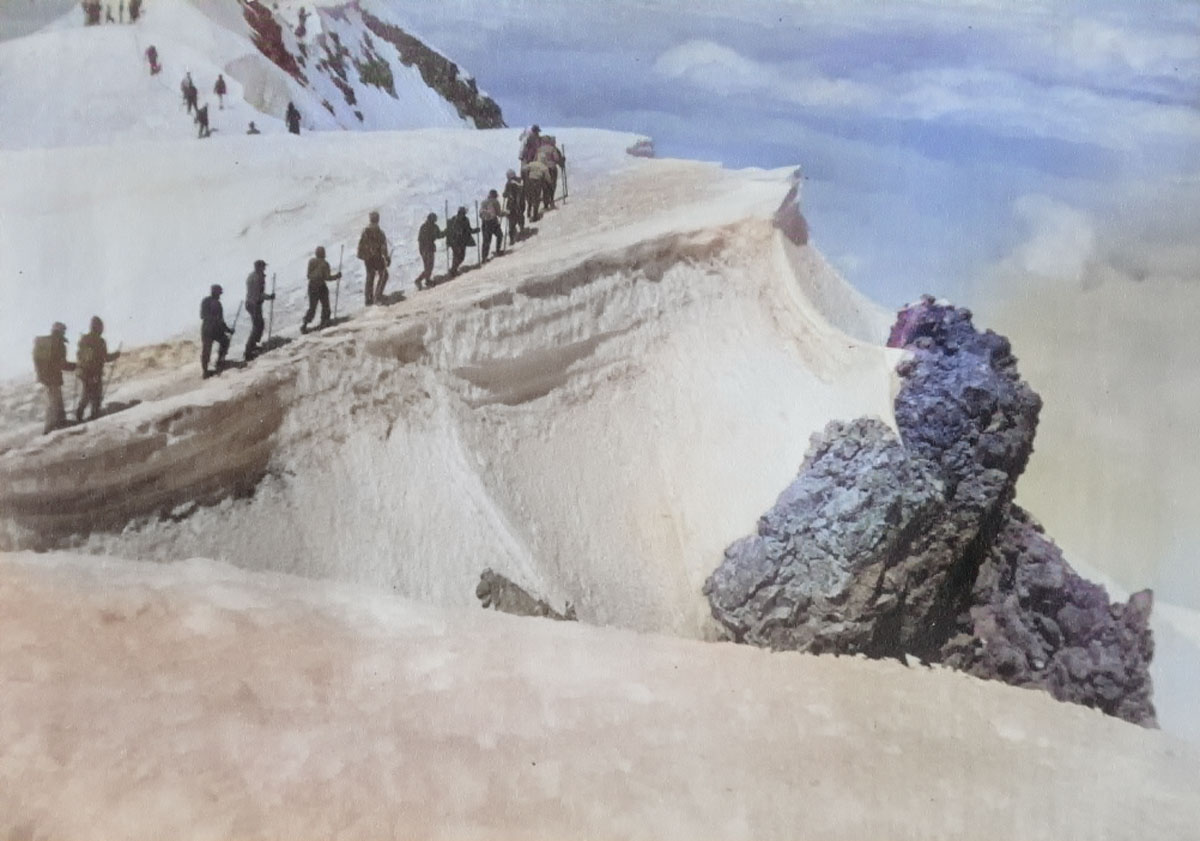

GS: I was first doing backpacking and then snow peak mountaineering. I really got my initiation into snow peak mountaineering in the summer of 1945, when I was fifteen, climbing from the YMCA camp at Spirit Lake. That was an old-style climbing party in which the guide was from Yamhill County, Oregon, an old gent who had climbed western snow peaks many, many times. He was the last per son I ever saw who wore the garb of the earlier generation of Pacific Northwest climbers, namely, stagged-off logger’s pants, caulked, twelve-inch logger’s boots, and a black felt hat. Instead of an ice axe, he carried a long alpenstock, and he covered his face with white zinc ointment to prevent sunburn. You look at early photographs in a Mazama yearbook and that’s the way everybody’s dressed. It was great! (Laughs.) I loved snow peak climbing from my first ascent there on Mount St. Helens. The next year, ’46, I signed up for a Mazama climb. I knew that the Mazamas led mountaineering trips every year. I did my first ascent of Mount Hood with the Mazamas, who were based in Portland. Having once or twice climbed a snow peak, you are eligible to apply for membership. I applied and was accepted, and one or two of my high school friends-all about the same age, sixteen-were accepted, making us the youngest people in the Mazamas at that time. That was the beginning of a youth group in the Mazamas, which was otherwise all middle-aged people. Then, shortly after, veterans back from the 10th Mountain Infantry came into the Mazamas. They had both war and mountaineering experience and were returning home to the Pacific Northwest. Those guys, I remember them well, became my generation’s–the sixteen-year olds–teachers in that era’s state-of-the-art snow and rock climbing. So we all went out climbing together with these twenty-five-year-olds who were very sharp and did winter camping, skiing, winter ascents, and so forth. It was a very good time to learn mountaineering, and the Mazamas hosted it. It was a great organization, and it’s still going.

JO’G: As one of the youngest people in the Mazamas, you published a piece in the 1946 Mazama annual. Was that your earliest publication?

GS: Either that or the Lincoln High School [Portland, Oregon] newspaper. (Laughs.) They were both published about the same time.

JO’G: That Mazama piece was prefaced with a laconic note from the editor that read, “This is a new point of view on mountain climbing” (56). It seemed as if he did not know what to make of this voice of a younger generation.

GS: That’s what it was, alright! (Laughs)

JO’G: You once told me about a climb you did on Mount Rainier, where you ran into some problems with ice fall.

GS: It was a Mazama climb, and we had made the summit via the south-side route up the Wapowety Cleaver. We were in descent. It was cloudy and warm, which is the worst kind of mountaineering weather. Quite warm and cloudy up there, and sort of heavy. We had to descend through some seracs. At one point, we were below an ice fall on a steep icy slope that was smooth-it was below a system of seracs about two hundred feet wide. Our return route led across the ice chute to a rock ridge that was well above any surrounding glacier and seracs, and was a safe place. I was the leader on the last rope, and we were all wearing crampons. The rope ahead of us went across. We would have followed right behind them-we had been following just a few yards behind-but my crampon ties had loosened up, so I stopped the group to tighten my crampons, and I urged everyone else to tighten their crampon straps, which took us five or six minutes. During those five or six minutes, an avalanche of broken seracs swept down the slope that we would have been right in the middle of if we had kept going. It was quite astonishing to see where we would have been. Then it stopped and froze up in a big jumble. As for the party that was ahead of us, their route had taken them out of our sight. They were around the comer of a rock wall, so they had no idea how we were, except that they had seen this avalanche come down too. So we all took a big breath and looked at it, and then we looked up. I said, “Well, you know, there’s no point in waiting here. There’s less chance that it’ll avalanche again right now than if we wait a little longer.” So we dashed across. We unroped, actually, and dashed across as individuals, with our ice axes and crampons. Close call!

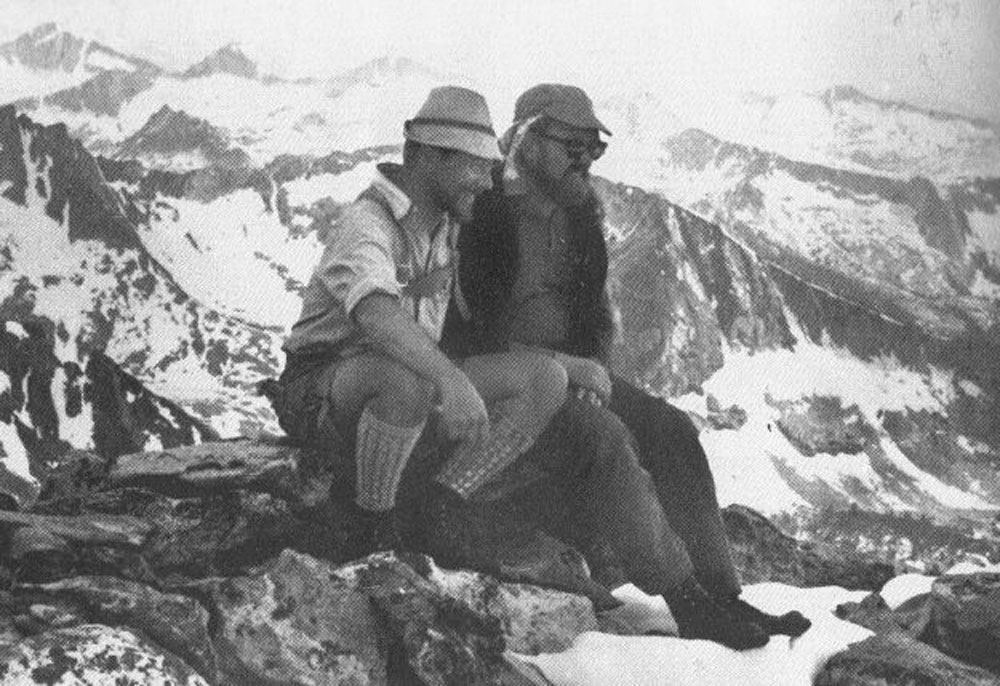

JO’G: In Earth House Hold, you included your journal from a 1965 ascent of Glacier Peak with Allen Ginsberg. Was that the only mountain Allen has ever climbed?

GS: The only snow peak that we had to rope up on, I’m sure! (Laughs.) He had done trail hikes, you know, up to mountains, but no, that’s the only time he put on crampons and ropes and things.

JO’G: Many people have asked you about the writers who have influenced you. What about mountaineers who have been influential?

GS: You know, I’m about to attend a three-day celebration of Willi Unsoeld at Evergreen College. I’m giving the annual Willi Unsoeld lecture, which is going to be a poetry reading. I was looking at a video of Willi before he died, giving a talk called “Spiritual Values in Wilderness”–boy, was he good! That guy was sharp!

JO’G: What will be the subject of your talk at Evergreen?

GS: I’m going to read from Mountains and Rivers without End and talk about Willi’s life as a teacher and mountaineer.

JO’G: Did you know him?

GS: Never knew him. He was only two years older than I, and he was from the Northwest. He was part of the same mountaineering culture that I grew up in, which is very romantic in a certain way.

JO’G: It’s hard to be a mountaineer and not be a romantic.

GS: Well, yeah, okay. (Laughs.) Except he got to Sagarmatha, Everest! When he was young, he and Tom Hornbein did the West Ridge traverse ascent. By the time I got to Everest, all I could do was stand around and look at base camp. (Laughs.) But seriously, Unsoeld, who died in an avalanche on Mount Rainier and was a professor at Evergreen College, was a brilliant, creative, bold, radical mountain man. I bow to him.

JO’G: Turning now to the subject of western American literature, the writers most frequently cited as precursors to your own work are John Muir, Robinson Jeffers, and Kenneth Rexroth. What other western American writers would you say have influenced you?

GS: I was an extensive reader as a kid and lived on a farm. We made really good use of the Seattle Public Library. It was a standard Saturday trip to the university branch of the public library to pick up a new round of books for me. I took out ten or twelve every week. I read John Muir very early on and was suitably inspired. I was inspired about how light he went. And this thing about having just a tin cup and a dry crust of bread and some tea (laughs)–l’m still not sure about that! (Laughs.) I read the biography John of the Mountains [Linnie Marsh Wolfe, 1938] when it came out. I also read a number of lesser-known people: Stewart Edward White’s novels about the Pacific Northwest and the West. Gad, I read everything. H. L. Davis, The Winds of Morning, a great novel about eastern Oregon. It catches the flavor of twenties and thirties eastern Oregon sheep and ranch culture really nicely. I like it better than Honey in the Horn, which was Davis’s most famous novel. Now get this (laughs): The Tugboat Annie series of stories, which were based in Puget Sound and which I read as a kid living in Puget Sound, came out serially in the Saturday Evening Post. (Laughs.) I also read some of the standard fare of western writers, including Zane Grey. Oh, and Oliver La Farge, the novel Laughing Boy, which was a very important novel to a lot of people and was quite a success in its own time. I’m sure it inspired D.H. Lawrence and a whole bunch of American Southwest lovers of that era, and brought a very sympathetic eye to Native Americans of the Southwest. It also has, as I recall, maybe the first account of a peyote vision, a peyote trip, in mainstream American literature–that’s way back there. I was doing this just a year or two before I discovered D.H. Lawrence and Robinson Jeffers, prior to reading standard literary fare, but it’s more like what a kid reads when he browses around.

JO’G: Do you regard your reading of Lawrence and Jeffers as somehow marking a transition in your development?

GS: Well, I became more self-consciously aware of quality and intellectual content in writing. Because of my connection with climbing and working with people in the logging industry, and a little bit of work in eastern Oregon around ranchers and loggers, I had been out on the ground long enough to know that these guys weren’t real westerners. (Laughs.) There is a level of writing in American western writing which does come pretty close to the ground, although it isn’t always considered high-quality writing.

JO’G: When you say “eastern Oregon,” do you mean that country east of the Cascades?

GS: Well, yes, the dry country. Madras, Oregon, for example. I worked around Madras, which is in sight of the Cascades, but it’s into the sagebrush. But at the same time, I was reading Native American stuff. My introduction to writing about Native Americans was very early, with Ernest Thompson Seton. Then I picked up all kinds of things, which I can’t even keep track of. l had a kind of double vision of the West, seeing it simultaneously from the Native American angle and from the white settler angle, which I think is typical of many imaginative people of the West–they see both sides of the picture in their mind’s eye. As far as my Native American interests went, oddly enough I didn’t just stick to the West and the Pacific Northwest. As we were taught as school kids up in Seattle, there were the “Canoe Indians,” and there were the “Horse Indians”–the Canoe Indians were on the west side of the mountains, and the Horse Indians were on the east side of the mountains–that’s the way we were taught to distinguish the cultures in the third grade. I also became very interested in the Native American cultures of New England and the Ohio Valley: the Shawnee and the Delaware and the Iroquois. I read a great deal about the Eastern Woodland Indians and their different cultural manifestations–I had a lot of interest in that. I had also read James Fenimore Cooper. And I read some horrendous novels about people like Simon Girty. I just reread a fine, dispassionate book on Girty that brought all of that back to me. Girty was a troubling figure to me as a boy. He was a white renegade who joined the Indians after 1778 or ’79 and fought with the Indians for the rest of his life. He was really demonized by the whites. Accord ing to the story, he delighted in watching whites being tortured that was a heavy torture culture anyway. Trying to establish Girty’s character in my own mind was a really interesting thing for me.

JO’G: Why was he troubling to you?

GS: He was troubling because I wanted to join the Indians, so to speak, in my mind, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to cheer when people were being tortured (laughs), as Girty supposedly did.

JO’G: In the genre of Indian captivity narratives, we find this motif of “going Indian.” According to those who analyze these stories, there is a kind of projection going on there on the part of Euro-Americans, an unconscious, deep-seated fear coming out. The most fearsome thing that could happen to a white person in these stories–even worse than being tortured–was for one to “go Indian,” to become one of the “savages.”

GS: Yes, I know that literature. Girty was at one time seen as virtually a demon; he was taken as an example of the worst case of what a white man can become. He moved to Canada, joined the British, and fought against the Americans on the side of the British in the Revolutionary War, because he said the British are better to the Indians than the Americans are. (Laughs.)

JO’G: In regard to this particular aspect of American culture the deep ambivalence about Native Americans and those whites who become involved with them–do you see this trend continuing down through history to the present, or does it disappear?

GS: I’m sure that that goes on, but one would have to think about how these threads reveal themselves today. There’s a big difference in the psychology of American culture in regard to Native Americans before the Civil War and after the Civil War. The experience of the East Coast and the Ohio Valley was one experience of Indians, and then the defeat of Tecumseh and the Euro-Americans winning the “Middle Ground,” as they called it, was the end of a period in Native American relations. That was the defeat of the Indians east of the Mississippi, basically. There’s a whole lore there, which we don’t think about much out in the West. After the Civil War, the expansion into the Plains begins, and there’s another whole chapter that starts with the Plains Indians. That’s the chapter we’re more acquainted with. The western Indian cultures–on the Plains and westward–were perhaps not as troubling to whites; the Plains Indians were not as demonized.

JO’G: The European encounter with Indians in California was very different too–the Spanish coming from the opposite direction of the English and French, and much earlier.

GS: It’s hard to figure out how the California Indian imagery plays, because apparently they were so decimated already by small pox by the time the Yankees came, you don’t get a clear picture of who they were in their own terms. When I was a youngster, what inspired me and influenced me greatly was the case of Chief Joseph. The history of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce, and their attempt to be free, led right into my political radicalism. And the connection with Charles Erskine Scott Wood. He was a Portlander, an anarchist, an IWW follower after he resigned his commission in the cavalry. He’s part of another chapter of American left-wing and West Coast left-wing life. There’s a pamphlet on him in the Western Writers Series. He has published several books of poetry–one called The Poet in the Desert. He’s a most remarkable American literary figure who started as a cavalry officer. He was present at the surrender of Chief Joseph and was so moved by the whole situation that he resigned his commission, moved to Portland, became a lawyer, and then became a supporter of the IWW and the socialist left. He later moved to Stanford, where his children and he–but mostly his children–became Stanford people and Berkeley people, living near the core of thirties left-wing activism in Stanford and Berkeley university circles. I know some of those people today–children of those children. One thing I should say: I am deeply imbued with a lot of western American political and literary lore–I grew up with it, through my mother, who’s a Texan who moved early to the Northwest, and my father, who’s native to Washington. What with the reading and the stories and the work, I guess I qualify as a westerner! I grew up in the left-wing branch of the western culture. So labor history, strikes, IWW, early socialism, people like Charles Erskine Scott Wood and Joe Hill were part of–were in–our thoughts to a certain degree.

JO’G: That’s a sort of subterranean current in the story of the West.

GS: Just a quick story: I worked with an Indian guy my age on a choker-setting crew in eastern Oregon in 1954. His name was Lyle Laframboise. He was a Wasco–big, handsome, cheerful guy. I asked him one day, “Lyle, where did you get that French name, Laframboise?” And he said, “Don’t you know? Laframboise was one of the great voyagers who came down the Columbia.” And it’s true! He was a descendant of the great Laframboise. You can read about it. (Laughs.)

JO’G: Let’s talk about the West Coast. You were born in San Francisco, a California native. The recently published Updating the Literary West [see Lyon et al.] devotes over 160 pages to California alone. In his introduction to the California section, Gerald Haslam writes, “Those who think California is ‘West Coast, not West’ simply don’t know what they’re talking about” (297). What is your take on California as a place and as a culture?

GS: California’s relationship to the arid West, the West that we think of as west of the Rockies, is always an interesting question. It does and it does not relate. In a certain sense, California is Pacific and Spanish. California’s culture comes around by sea to it, or up from Mexico, rather than across the Great Basin. My friend Drum Hadley, a cowboy, poet, and sustainable rancher who used to really study this stuff, says that older-style California ranchers and cowboys had far more Mexican lore and Mexican-derived gear around the ranch than anyone did in Arizona or Texas. He says these early California ranchers were deeply Mexican (Spanish) influenced, and he could see it in the kinds of knots they tied and in the way they did their rawhide braiding and in certain ways they handled horses. Drum says some of the knot systems go, via the Spanish, back to North Africa!

JO’G: An awful lot has been written about your work in relation to landscape and nature, but comparatively little about your relationship to West Coast cities. You were born in San Francisco and then raised in Seattle and Portland. To what degree would you say these cities are western?

GS: Well, again, the West Coast is and is not part of the West, depending on how you define it. It’s not part of the “Dry West” or the “Rancher West.” I believe that if you define part of the western story as direct resource use, men and women working very close to resource extraction–which I think is a fair way of looking at it then the whole logging industry, and to some degree the mining industry, should be brought into it. But logging and mining have not created myths or stories like ranching did, and I’m not entirely sure,why. If there’s a romance of logging, it’s more of the politics of the IWW days and the strikes–labor strife romance. They never tried or if they did, it never worked-to organize cowboys, though the IWW was out organizing Montana miners and the loggers in the woods. Anyway, Portland and Seattle are one set of cities, San Francisco is another. San Francisco is a Mediterranean city, originally dominated by French, Portuguese, and Swiss-Italian settlers, all Catholic. Kenneth Rexroth was very articulate about this–he gave me my sense of San Francisco and Bay Area culture, and the old power elite of San Francisco, who were graduates of the Jesuit high school and the University of San Francisco. The Aliotos, for example. Really, I felt San Francisco to be like a cosmopolitan European city when I first came here. The Northwest–Seattle, when I was a kid–was a faintly Scandinavian town. And Portland not quite so Scandinavian, more like a transplanted Boston–it is more like a New England city. These are all interesting speculations. But I didn’t live in Seattle. I lived out of Seattle on a farm, so Seattle was not really a city that I knew. I was never intimate with it. I was intimate with the countryside north of Seattle, the Puget Sound country and the woods, but not the town really, except to go in as far as the University District to the Goodwill and to the library. I went to college in Portland, and Portland is (in certain ways all of Pacific Northwest culture is) kind of uniquely liberal–and I’m not sure where it all comes from. But it includes the radical Swedes, Finns, and New England Unitarians, who became part of the early Portland scene.

JO’G: Did living in Portland have a decided influence on your work, your evolving sensibility?

GS: Not so much as my connection with the Cascades to the east and the Pacific to the west. You know, one of the things I think that would be said about me as a westerner would be that I placed myself regionally, really very early, and by landscapes. So the bioregional threads in my thinking actually go back a long ways. The ideas in my essay “The Rediscovery of Turtle Island” are actually very old ideas for me. I’d say that suggests another kind of westerner–the westerner who bonds with the place early on as a kid and for whom the place is the source of their loyalty, not the political system or the nation-state. But then that’s not only western–that’s the old ways.

JO’G: On the subject of bioregionalism, those same ideas that you had early on about one’s relationship to place and identity have now entered into contemporary academic and political discussions. Where did all this discussion of bioregionalism come from? Where is it now? And where is it going?

GS: Oh, that’s a huge topic! (Laughs.) Of course, the term was borrowed from biogeographers to begin with. And we put a spin on it ourselves, which was social and cultural. But in a sense we were looking for any language that would help us clarify that there was a distinction between finding your membership in a natural place and locating your identity in terms of a social or political group. The landscape was my natural nation, and I could see that as having a validity and a permanence that would outlast the changing political structures. It enabled me to be critical of the United States without feeling that I wasn’t at home in North America. They used to say, “If you don’t like it here, go back to Europe”–which is to assume that your identity is entirely that given to you by being a member of the state and that you have no stake in the landscape. It’s very revealing. I’m sure many people have discovered that, as a matter of their own sensibility, their loyalty is to the land, but they haven’t easily found a way to articulate it in their lives. Then they become environmentalists or something, but they don’t bring it into the foreground of their thinking. They don’t understand that loyalty as an alternative political-cultural-personal strategy. I would suggest that the terminology comes way after what is actually a shift in sensibilities and that the feeling for the landscape has been present in some territories of American life from the beginning. It is simply penetrating deeper and deeper as the “newcomers” stay around longer. It’s a nascent sensibility that, I think, marks the future of western writing, something we’ll see more and more henceforth in various forms, whether it’s called “regional” or “bioregional.”

JO’G: This ties in with the essay by your wife, Carole Koda, which is titled “Dancing in the Borderland: Finding Our Common Ground in North America,” a piece she published in a little book along with essays by you and Wendell Berry. [This essay is reprinted in Terra Nova 3.4 (fall 1998).] She discusses how ethnic identity merges with place sensibility.

GS: Yes, Carole finds that the place provides more of her being than her ethnic background, although she honors it. That little essay is very interesting. It points a way beyond unreflective identity politics to the serious consideration of membership in North America. Now, here’s one more little thing about the West: huge public lands. When I was still a teenager, I woke up to national forests. I grasped that much of the land around our place were national forests and took great comfort in its vastness. That may have been misplaced, looking at the history of the Forest Service since, but it gave me as a youngster–out of my backpacking trips and hitchhiking trips and so forth–a sense of a stake in the land. It brought me cheer to think that we had huge areas of open space and wild land and forests that belonged to all of us. That’s part of the American western experience, whether people realize it or not. It’s not just that there’s open space there and that it’s big, but that it’s public land, the Commons. I finally tried to refine some of my thinking and writing about public lands, in the essays in The Practice of the Wild, and to translate that into a sense of the historical institution of the Commons. Now none of this would come out of anybody’s interest in Asia! (Laughs.) These are very American interests: that the Commons might still survive.

JO’G: The Practice of the Wild has been around for several years now. What’s your feeling about the critical response to that book?

GS: The critical response has been a little disappointing, in that I have not yet seen–with one exception, which I’ll come to–what I thought was a really reflective review of it. It’s had lots of favorable reviews, with many good things to say. But there are some angles in Practice that people are still going to stumble onto yet. It’s a complex text. It has not been picked up very much by the official environmental world, but it’s been used steadily as a textbook all over the country, in many universities. I think that’s what one of its uses is, a textbook. There is a dissertation on it now by a woman named Sharon Jaeger, who lives in Alaska. She got her Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins. It’s called “Towards a Poetics of Embodiment: The Cognitive Rhetoric of Gary Snyder’s The Practice of the Wild.” It’s a very sharp, pro-wilderness, postmodernist assessment of it. So I’m charmed by that. There’s a post-West, “western” book for you, The Practice of the Wild!

JO’G: Using Practice in my own classes, I have found that students consider it a very challenging text.

GS: Yes, I guess that the demands it makes might be unfamiliar. There’s an aspect there that is not part of mainstream intellectual life. We are just beginning to have a few “intellectuals” who are also nature literate.

JO’G: We need to be looking for Forest Service people who are reading The Practice of the Wild.

GS: You know, Forest Service people do read The Practice of the Wild. I get letters from some of them every once in a while.

JO’G: People coming up in the ranks!

GS: Yes! (Laughs.)

JO’G: Has your involvement with the Yuba Watershed Institute over the last several years had a significant influence on your writing?

GS: Let’s see. There are a couple of essays in A Place in Space that came directly out of working around here [on San Juan Ridgel, “The Porous World” in particular. And actually (laughs), they are some of my favorite little essays! It’s hard to say. Right now we’re scrabbling around in the ongoing problems of how to deal with the U.S. Forest Service, which has infinite ways of avoiding being responsible, as we keep finding. How a community interacts with the public lands management policies, and how a community keeps the public lands employees focused, is the challenge of this. It is going to be a long, hard haul. To transform public lands management in America is going to take a lot of people who stay pretty much in place and who hold the public lands managers’ feet to the campfire–you know, to make them realize that there are living people involved in the lands. That would be a whole book in itself, except I don’t know if I’m the one who’s going to write it. I’d have to say that the effect of all this political work may be more spiritual in my writing than visible in quite such an obvious way.

JO’G: Between Turtle Island, which seems to be the most overtly political of your bigger books, and the books you have published since, there seems to be a translation of the way political involvement manifests itself. It is interesting to read those critics who praised Turtle Island, but when it came to Axe Handles, they either did not know what to say or they said, “Well, it’s okay, but it’s not up to the standard of Turtle Island.”

GS: There are a lot of people–and I grew up with them–for whom “political” means trying to affect public policy in obvious ways by political activism. Something of that does surface in Turtle Island. The approach of working, empowering, rooting in, and getting community consciousness established is much slower and is not nearly as obvious. The points in Axe Handles, a lot of them, are about what happens when you stay in a place in time. You go into various sensibilities about a place, and some people just aren’t bright enough to see that that’s political! (Laughs.) Although in bioregional terms that is political. Axe Handles is a description, an account in many ways, of coming into the community and coming into the place in many subtle ways. From there, I took the idea of “Turtle Island” as a new narrative, which I write about in my essay [“The Rediscovery of Turtle Island”] in A Place in Space. Somebody wants to talk about new narratives for North America, okay, here’s a new narrative. It’s really thrown out there as a kind of challenge: to drop the United States and to drop America and to think in terms of Turtle Island, to think in terms of ten thousand years on the continent instead of five hundred years. Again, most political, educated, intellectual type people don’t quite get it yet. That belongs to the next generation, I think.

JO’G: Turning to No Nature. Many readers say something like, “Well, here’s a collection of selected poems, but we’re just waiting for Mountains and Rivers without End.” It seems to me that this is a unique book unto itself, with its own design and purpose.

GS: Oh, yes, it’s deliberately selected. It’s not as tight in quite the same way as Mountains and Rivers is, but it has its own coherence, that’s true. That’s the major part of my poetry right there!

JO’G: Your career at this point is bracketed by two major long poems: Myths and Texts early on and the recently published Mountains and Rivers without End. To what degree is Mountains and Rivers a work in the tradition of western American literature?

GS: In a sense, what I’ve done is globalize the West. It began for me with working on lookouts and seeing the huge spaces that you see from high peaks, to the point that when I saw Chinese landscape paintings, I thought, “Now these people had a way of seeing that, of representing that kind of huge space.” I wondered if there is a way of representing huge space in poetry. Reflecting on this challenge finally led me to launch into the project. It was the North Cascades from Sourdough Mountain and Crater Mountain lookouts for three months each–almost six months in two subsequent summers, being soaked in that–that really got me going on the idea of how one can deal with space in a poem. You begin to see it in the poem when you get to “Bubbs Creek Haircut” and look around the Sierra Nevada. But then the poem meanders and convolutes in a lot of ways and ends in the space of the Great Basin. It starts and ends in the West, and is never far from it but uses the western landscape as a metaphor for the whole planet.

JO’G: Do you see what you are trying to do in Mountains and Rivers as being in any way similar to what Charles Olson talks about in Call Me Ishmael, where he opens with that passage on “SPACE” (11)?

GS: I took that to heart, and I think Olson was right. In a sense I’m taking up the suggestion that Olson offers there, seeing what can be done with it. But I also translate space from its physical sense to the spiritual sense of space as emptiness-spiritual transparency–in Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, and that’s a significant element in Mountains and Rivers too, the play between formal landscapes and impermanence, emptiness, throughout the poem.

JO’G: The Mahayana notion of emptiness, shunyata, how would you explain what it means to people unfamiliar with this Buddhist term?

GS: Well, I wouldn’t. If I wanted to talk about shunyata in Mountains and Rivers, I would have. What I’ve done there is give the concrete correlative in the poem, so I would say, “You want to get some sense of shunyata, read the poem.” (Laughs.) The poem cuts back and forth across the different levels of what that term might imply. Certain people will always pick up the term shunyata and just try to define it, but it’s best defined in terms of images or metaphors or experience.

JO’G: The Black Rock Desert?

GS: Yes. Or transparency, or space–you have to use an interconnection–space, transparency, solidity, irreducible solidity, total emptiness. (Laughs.)

JO’G: In our discussion yesterday, you remarked about the western American landscape being transformed into a Buddhist landscape. What did you mean by that?

GS: (Laughs.) Well, that’s a little bit about what Mountains and Rivers tries to do. But I’d better say “cosmic landscape” or “mind landscape.”

JO’G: Do you see other writers doing that at this point?

GS: Well, yes, Philip Whalen has done it all along. And so did Lew Welch. Look at Lew’s lyric Klamath River poems in that light! If we don’t need to call it “Buddhist” but instead work at “process,” we can see it in the work of Jerry Martien, Michael McClure, and Jim Dodge–and then Tim McNulty, Michael Daley, and Sam Green, three Puget Sound poets.

JO’G: What might a Buddhist landscape be?

GS: That’s a nice question. A Buddhist landscape would be a living landscape. It would not just be rocks and minerals and plants, etc. It wouldn’t be an assemblage of things. It would be a spiritual ecosystem, an energy-flow model. It would be like a Chinese painting trying to present landscape–it would be matter in process. It would be landscape as, in the words of one Chinese landscape painter, “solidified Tao”–energy in its hard form rather than energy in its fluid form. Rocks and waters are complementaries to each other, not opposites, is one way to put it–which is part of the way Buddhism becomes translated into Chinese painting. Landscapes seen in that way are not the world of Cartesian thinking: material forms wearing out and running down in time. More as per modern physics, they are a remarkable flow which has many levels of simultaneous being. That would be a Buddhist/Taoist landscape: the land as the Way in motion.

JO’G: Well, is there anything else you’d like to say about yourself as a western writer?

GS: Oh, I’ve said too much already! (Laughs.)

WORKS CITED

Bingham, Edwin R. Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Western Writers Series #94 (Boise, Idaho: Boise State University, 1990).

Lyon, Thomas, et al., ed. Updating the Literary West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1997.

Olsen, Charles. Call Me Ishmael. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Snyder, Gary. Mountains and Rivers without End. Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 1996.

–. The Practice of the Wild. Berkeley: North Point Press, 1990.

–. Turtle Island. New York: New Directions, 1974.

–. “A Young Mazama’s Idea of a Mount Hood Climb.” Mazama 28.13 (1946): 56.

.