Lester Rowntree: Vernacular Natural Historian

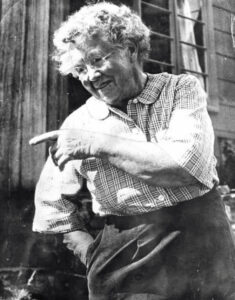

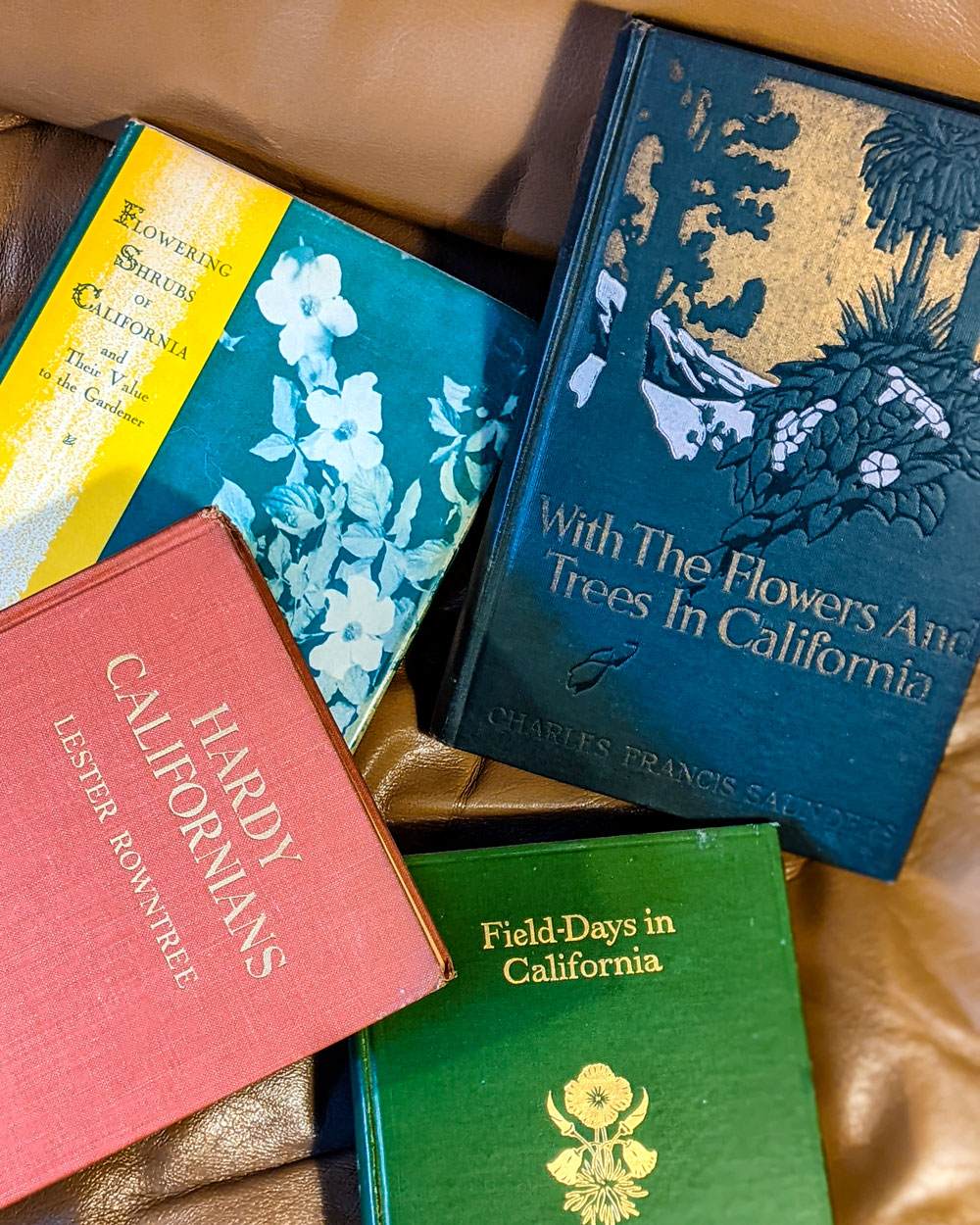

“As I settle down, relearning how to live the well-rounded life, I begin to perceive that the tame, as well as the wild, has its place when it comes to collecting myself.” So wrote the horticulturalist Lester Rowntree in 1950, her seventy-third year. She would live for another twenty-eight, complete a century of human life, but she was on the threshold of difficulties. The infirmities of age would soon assert themselves, begin to clip her zest—as well as the ambitiousness of her plant collecting itinerary. There were emotional tribulations as well. In the previous year, her “working shed”—a twelve by twelve foot hut where she did all of her writing, kept all of her fieldnotes and manuscripts—burned to the ground under mysterious circumstances. Although she seldom showed any signs of it, the fire had altered the inner-landscape of her psyche. Consumed in the flames, apparently, was all of the work—notes from two decades of gathering—which was to have become her third book, the capstone to a trilogy about California native plants. The first and perhaps best known of these volumes was published in 1936. Titled Hardy Californians, it is an account of the state’s bewildering mosaic of flowering annuals. The second book, coming out in 1939, was called Flowering Shrubs of California. The third was to have been devoted to the trees and forests of the Golden State. Her books—as well as her hundred or more published articles—are the record of a three decade search for native flora, a record made all the more remarkable in that she embarked on this solitary quest after turning fifty years old. She divorced her husband and then hit the roads—and backcountry trails—with a mission: to alert Californians and the world to what was being lost—namely, California itself.

“As I settle down, relearning how to live the well-rounded life, I begin to perceive that the tame, as well as the wild, has its place when it comes to collecting myself.” So wrote the horticulturalist Lester Rowntree in 1950, her seventy-third year. She would live for another twenty-eight, complete a century of human life, but she was on the threshold of difficulties. The infirmities of age would soon assert themselves, begin to clip her zest—as well as the ambitiousness of her plant collecting itinerary. There were emotional tribulations as well. In the previous year, her “working shed”—a twelve by twelve foot hut where she did all of her writing, kept all of her fieldnotes and manuscripts—burned to the ground under mysterious circumstances. Although she seldom showed any signs of it, the fire had altered the inner-landscape of her psyche. Consumed in the flames, apparently, was all of the work—notes from two decades of gathering—which was to have become her third book, the capstone to a trilogy about California native plants. The first and perhaps best known of these volumes was published in 1936. Titled Hardy Californians, it is an account of the state’s bewildering mosaic of flowering annuals. The second book, coming out in 1939, was called Flowering Shrubs of California. The third was to have been devoted to the trees and forests of the Golden State. Her books—as well as her hundred or more published articles—are the record of a three decade search for native flora, a record made all the more remarkable in that she embarked on this solitary quest after turning fifty years old. She divorced her husband and then hit the roads—and backcountry trails—with a mission: to alert Californians and the world to what was being lost—namely, California itself.

Born Gertrude Ellen Lester on February 18, 1878 in the Lake District of England, she came with her family in 1889 to America, where they settled on the Kansas prairie. Late in life this immigrant recalled seeing Indian campfires on the horizon. “I tried to run away to live with the Indians. In England I had tried to run away to live with the gypsies to escape the surveillance of nurses and governesses. I never got to know the gypsies or the Indians, but I got to know the open Kansas prairie.” From the start, “Nellie” Lester was a difficult personality to contain, though she could be grounded in the earth—by tending a garden. Thus when she was sent away to boarding school in Pennsylvania, she was “given a patch of ground to keep her from running away.” A tradition at this same Quaker boarding school—that of students addressing one another by surname—prompted her to “shed the names Gertrude Ellen” (Hamann 4). She liked being called Lester. When at age thirty-one she married Bernard Rowntree, she took his surname but kept her own, rendering last unto first. For the rest of her life she enjoyed the confusion her name generated in others: people who hadn’t met her—including many customers of the seed company she ran for years out of her Carmel home—assumed she was a man. She often received letters with the salutation “Dear Sir.”

Lester Rowntree was a vagabond by nature. This was reflected in the methods she chose to pursue knowledge. Her formal education ended with high school. Completely self-taught in botany, she relied on the works of the professional scientists Willis Jepson and Alice Eastwood. When asked in her later years if she regretted not having a university education, Rowntree replied: “That would spoil everything. . . . It would be all what you learned—put on—veneer—pretense.” She was a vernacular natural historian in the sense that she was attuned to the native idiom of her subject —the place we call California—and she adapted her perception according to its requirements, eschewing any temptation to make her inquiries conform to scientific standards, including those of style. When Hardy Californians was re-issued in 1980, the reviewer in Fremontia, the journal of the California Native Plant Society, wrote: “I think to approach Hardy Californians primarily for ‘hard’ information would be to defy the author’s intent. It is, above all, an ode of esthetic appreciation, not merely to specific California native plants, but to the entire California landscape as it existed for Lester Rowntree. It is her vehicle for cajoling and beguiling us into a greater love of the natural world.” The properly trained scientist is loathe to cajole and beguile; to do so threatens objectivity, not to mention professional reputation.

she relied on the works of the professional scientists Willis Jepson and Alice Eastwood. When asked in her later years if she regretted not having a university education, Rowntree replied: “That would spoil everything. . . . It would be all what you learned—put on—veneer—pretense.” She was a vernacular natural historian in the sense that she was attuned to the native idiom of her subject —the place we call California—and she adapted her perception according to its requirements, eschewing any temptation to make her inquiries conform to scientific standards, including those of style. When Hardy Californians was re-issued in 1980, the reviewer in Fremontia, the journal of the California Native Plant Society, wrote: “I think to approach Hardy Californians primarily for ‘hard’ information would be to defy the author’s intent. It is, above all, an ode of esthetic appreciation, not merely to specific California native plants, but to the entire California landscape as it existed for Lester Rowntree. It is her vehicle for cajoling and beguiling us into a greater love of the natural world.” The properly trained scientist is loathe to cajole and beguile; to do so threatens objectivity, not to mention professional reputation.

Lester Rowntree, on the other hand, had no worries about containing her personality. She flaunted it. A free radical, she could afford to be subjective, merge with her interest and not have to hide or disguise it. This was her standard, her style. “Her writings do not contain any scientific references,” recalls one botanist, James Roof, who knew her well. “She just went out into the field and enjoyed it, and passed her sense of joy on to the reader.” Rowan Rowntree, one of her two geographer grandsons, makes a similar observation: “One starts as an amateur, even with university degrees. And Lester became a professional in the way I think each of us would like to. The continued pursuit, the standards, all in order to find out what’s going on out there in the real world. She was intimate with her world, and she had that wonderful capacity to communicate that intimacy and knowledge to those who were interested” (185).

Lester Rowntree was the kind of naturalist who has all but disappeared from our contemporary universities, in the wake of molecular biologists and geneticists who, in transferring their inquiry to the field bounded by the prudent lens of the microscope, pursue nature through complex computer modelling and the science of big numbers. Field biology is unpopular among the grant-makers. It has for the most part become a vernacular pursuit. In this sense, for us, Lester Rowntree’s life and work glow with significance. As her namesake grandson describes her: “She set a model of independence. One pursued science on one’s own. She never had great respect for laboratory science, and she certainly made it quite clear that if you were going to do science, you did it in nature. She lived by that—.” Contemporary ecologists, looking for a way to rescue their discipline from theoretical irrelevance, could well turn to naturalist writers such as Rowntree to see how the study of the World might be reinvigorated by a return to the tradition of natural history, and there recover the narrative’s capacity to “bring things together.” Isn’t this, after all, what the science of ecology was intended to accomplish in the first place?

Through Rowntree’s writing we may catch a glimpse of a California often seen but so frequently overlooked. We are estranged from that which is most familiar. The natural facts. Rowntree’s purpose as writer is to cultivate in her readers a literacy of nature. Her words are directed toward the laity, the non-scientists, which includes nearly all of us. She points to the startling fact of California, which is simply the emergent property of an infinite assemblage of startling facts, the first of which is our climate, itself a most beautiful conspiracy of forces we can only guess at. Winter rains and summer drought. Climatologists—for their own obscure reasons—call it a “Mediterranean climate.” An odious comparison lurks in this appellation. Let’s instead call it what it is: the California Climate. “Rain makes the year,” Rowntree reminds us, “the lack of rain mars it, and the seasons depend upon it absolutely. If the rains are scanty, everything and everyone is worried and depressed. If, as sometimes actually does happen, they are plentiful, the whole state, and all therein—except perhaps the winter tourist—rejoices.”

Through Rowntree’s writing we may catch a glimpse of a California often seen but so frequently overlooked. We are estranged from that which is most familiar. The natural facts. Rowntree’s purpose as writer is to cultivate in her readers a literacy of nature. Her words are directed toward the laity, the non-scientists, which includes nearly all of us. She points to the startling fact of California, which is simply the emergent property of an infinite assemblage of startling facts, the first of which is our climate, itself a most beautiful conspiracy of forces we can only guess at. Winter rains and summer drought. Climatologists—for their own obscure reasons—call it a “Mediterranean climate.” An odious comparison lurks in this appellation. Let’s instead call it what it is: the California Climate. “Rain makes the year,” Rowntree reminds us, “the lack of rain mars it, and the seasons depend upon it absolutely. If the rains are scanty, everything and everyone is worried and depressed. If, as sometimes actually does happen, they are plentiful, the whole state, and all therein—except perhaps the winter tourist—rejoices.”

One more thing about the California Climate: there’s no such thing as what the professional weather forecasters and other mythmakers routinely refer to as a “normal” year. Experience proves otherwise. Rowntree shows how the native wildflowers respond to this fact: “There are really two springs in California, the extra one coming in the early winter months. But every year the seasons run differently. The rains slide them forward or backward like beads on a string, lengthening one and shortening another. Most wild plants are pleased with the rains, whenever they come, and show it; but there are always a few—a different few each year—which are displeased, the moisture not arriving at the moment when they most need it. So these latter species do not or cannot flourish luxuriantly, and thus the pattern of wild bloom is never twice exactly the same.” “Normal,” in the way we so often use this word, is the scat of an academic discipline—the social sciences. Nature is not “normal” but fluent. The aesthetic lesson Rowntree derives for us from the natural world is simple: Each moment is a work of art, insisting upon its own individuality, an individuality that will not be contained by the integers of statistics. Nor does this lesson contradict what many people cite as the first law of ecology, never expressed more eloquently than by that Scottish immigrant John Muir: “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” Not a contradiction but a paradox.

Climate and geography and time (if we can separate them, so to speak) all perform a dance, reeling out in one of the richest floras per square mile on earth. A rare fling of habitats. We call it California. But the name “California” is less often applied in this natural sense than in the various cultural senses: Hollywood, Alcatraz, Beverly Hills, Sea World. The first synonym for Tahoe is “casino.” And Magic Mountain belongs to no range—it rises as our self-fashioned monadnock. Most of California’s human immigrants come here having dreamed the Golden Dream, but many never wake up. When they speak of California they do so in a foreign language. Those who do awaken, however, begin to see the older, deeper California that Rowntree describes:

It often happens . . . that those features which the newcomer to California most dislikes are the very ones he eventually comes to love the most, while those over which he at first goes into raptures bore him terribly later on . . . But by and by, when California is really his home, the first loves take second place and the things which most tug at his heartstrings are the very things which at first repulsed him. The desert becomes friendly instead of forbidding, the amber panne-velvet hills, buttoned down with dark green Live-Oaks, begin to seem beautiful, and the chaparral which stretches along mile after mile is no longer a dark smudge on the landscape but a tapestry-like breadth of California’s garment.

Rowntree’s works can be read as the spiritual autobiography of on an immigrant who transformed herself into a native. This is the task that each of us living in California needs to perform: Regardless of where we were born, each of us must become a native Californian.

Immigrant versus native—so often the source of political conflict, but equally a source of psychological conflict. By directing our attention to the natural world, Rowntree’s work offers—if not resolution, certainly a coming to terms with the tension, both on an individual and cultural level. The conflict is implicit in the language itself, in the very words “immigrant” and “native.” How do we use them? The word “immigrant” seems the easier of the two to grasp. My dictionary only lists two senses for this word, the first applying to human beings: “One who leaves a country permanently to settle in another.” The second is more inclusive of beings other than human: “An organism that appears where it was formerly unknown.” Yet to constellate the most frequently used synonyms for “immigrant” is an exercise in negative connotation: invader, alien, intruder, foreigner, stranger, outsider, barbarian. Somewhat less derogatory are the synonyms “exotic” and “newcomer.” When referring to plants that are immigrants, one often employs the epithet “weeds.”

When I turn in my dictionary to the entry for the word “native,” I’m overwhelmed by a comparatively lengthy entry, and I hardly know where to begin. Etymologically, the word is linked to “natural,” so immediately the taxonomist of words is confronted with complexity. One of the senses for the word works by way of contrast: “indigenous, as opposed to exotic or foreign.” As opposed to “immigrant.” When we voice the word “native” today, it is almost always with a warm fuzzy feeling. Certainly the people driving the cars with the bumper stickers that proclaim “Native Californian” are hawking the word with positive connotations, not to mention a smug essentialism. When I use the word “native” I too intend positive connotations, but I harbor a skepticism about the unexpressed political implications that lie behind most uses of this word.

So in the quest for a more “neutral” source, I’ll turn to a biological definition, this one drawn from an article that appeared in the premier issue of Kalmiopsis, the journal of the Oregon Native Plant Society: “Native means indigenous, originating in a certain place.” Short, simple, useful. So far so good. But the authors go on to caution us: “Three issues complicate the application of this definition to native species: the geographical distribution of species, changes in species distribution through time, and genetic variability among individuals of the same species.” The word “native” quickly becomes slippery. Lester Rowntree, with her usual clarity, brings this same point home to her readers: “In their own haunts the wild flowers are the aborigines and the foreign weeds the invaders, while in the garden the roles are reversed and the plants we call weeds consider the introduced wildflowers the intruders.”

Society: “Native means indigenous, originating in a certain place.” Short, simple, useful. So far so good. But the authors go on to caution us: “Three issues complicate the application of this definition to native species: the geographical distribution of species, changes in species distribution through time, and genetic variability among individuals of the same species.” The word “native” quickly becomes slippery. Lester Rowntree, with her usual clarity, brings this same point home to her readers: “In their own haunts the wild flowers are the aborigines and the foreign weeds the invaders, while in the garden the roles are reversed and the plants we call weeds consider the introduced wildflowers the intruders.”

As is true of ecological communities, the definition of the word “native” is dynamic, highly interactive, impossible ultimately to pin down. We ourselves need to be adaptive in our use of the word, if we as humans wish to avoid making a pesky cleavage between ourselves and the rest of the world. That “invasive weed” called filaree now found throughout California is not a “native” by any botanist’s definition. But as I look at a particular filaree growing in these grasslands, I am very aware that it originated and is growing in this certain place—it is of this place—which is the biological definition of the word “native” that I cited above. I myself was born in Newark and raised in suburban New Jersey; I moved to California seven years ago. I don’t know if I will die here. Who am I to call this plant a weed? Immigrant or native, it all depends on the perspective.

From the perspective of Natural California—the California of Lester Rowntree, John Muir, Mary Elizabeth Parsons, Charles Francis Saunders, and a host of other vernacular natural historians—all of us are immigrants, even those of us who were born in the state. To speak more accurately, we should admit that all of us are natives of post-modernism, and Disneyland is our capitol. If we wish to live closer to Natural California, we need to move there in our hearts, in the psychological and indeed spiritual sense. Lester Rowntree, Englishwoman by birth, made such a move. We too may begin to make the move, when we make the effort to learn about the plants and animals—not only their names and how they might be useful to us, but how we might be useful to them. They are the true natives of this place. They were the teachers of the first wave of human “invaders” who arrived on this continent from Asia, the ones who themselves became Native Americans.

This brings us back to the importance of the vernacular, which is a question of style. When asked what he believed was Lester Rowntree’s greatest contribution to California Native Plants, the botanist James Roof replied that it was her writing style. He went on to explain: “She has a style of looking upon native plants almost anthropomorphically and gets away with it. She doesn’t attribute human traits to them and she doesn’t write purple prose about them, but she can certainly conjure up beautiful writing about native plants without being maudlin.” Her writing style blossomed from her lifestyle. As Rowan Rowntree describes his grandmother: “I always saw her as sort of a modern-day Francis Bacon, working empirically—trying this and trying that, but having a keen sense of what was right and what would work.” Lester Rowntree’s namesake grandson referred to her an “intuitive ecologist,” by which he meant she relied on “this kind of feeling.” He explains: “If you just have enough experiences coming across rattlesnakes, you will certainly understand what the conditions of their niche might be and where you’ll find them. She knew about everything It was something that complemented the textbooks.” More than complement, it is the knowledge that both precedes and comes after the textbooks. It is the matrix within which all  textbooks are subsumed. Style is an adaptive response, as in writing so in living.

textbooks are subsumed. Style is an adaptive response, as in writing so in living.

“I didn’t take up this job for the poetry of it,” Lester Rowntree wrote in a 1939 essay titled “Lone Hunter.” “I had no ambition to become a Picturesque Lady-Gypsy. I honestly wanted to find out about California wild flowers. There was little written about them in their habitats and nothing at all about their behavior in the garden, so I made it my job to discover the facts for myself.” And the facts set her free. Rowntree pursued her bliss, an immigrant who remade herself into a native, and in so doing walked out into a spectacular freedom. It all seems so simple, but the price is higher than most of us are willing to pay. “It took adversity to bring me the sort of life I had always longed for,” Rowntree confesses. “Not until after my domestic happiness had gone to smash did I realize that I was free to trek up and down the long state of California, to satisfy my insistent curiosity about plants, to find them in their homes meeting their days and seasons, to write down their tricks and manners in my notebook, to photograph their flowers, to collect their seeds, to bring home seedlings in cans just emptied of tomato juice.” How many of us have the freedom “to trek up and down the long state of California?” Or even spend a single summer in the Sierra? Perhaps a lack of freedom prevents us from loving this place in the way so many of us wish it were loved. The advice Rowntree offers: “The point is to follow the plants’ own quite unelaborate rules for the conduct of their lives.” To over-invest in the “elaborate” can only be done at great risk: “Plants, like people, develop complexes and inhibitions when they find themselves in unhappy environments.”

Lester Rowntree was a cultivator of native plants, but in so doing was cultivating her own California identity. Her example opens a door for all immigrant readers. As is, each of us who is an “alien” has a vast horde of “domestic” animals overgrazing the fields of the imagination; the “exotic weeds” run rampant as we continue to be K-Mart selected. But there’s also a pristine “California” within each of us—with the whole “native” ecology intact: flora and fauna and even indigenous peoples. Each of us—or so I imagine—can blaze a path such as Lester Rowntree did: to go out, to learn, to know, to bring something back. We may not collect plants, but each of us may be able to collect a little bit of ourselves. To cultivate our own “gardens”—which I take to mean our character, both individual and cultural—is to become California-native, to go from “amateur” to “professional” in the good sense that Lester Rowntree accomplished. In the end, in writing, in style, in character—it’s all the same: the quest for a native insight: collecting it in the wild, bringing it home, and cultivating the vision.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally published in the inaugural issue of ISLE (Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment) in 1993.