The Unhappy Case of the Catskill Mountain Violinist

Frederick F. Hapeman is but one of the many forgotten artists of the Catskill Mountains. We know he was an artist because that’s what he told the army captain who came through Windham, New York, in June of 1863 to register in a compendium the names of all men eligible for military service. The Civil War was raging. Fresh recruits were needed. The captain duly recorded for posterity the pertinent details of each man’s life: name; age; marital status; and profession, occupation, or trade. Frederick Hapeman was in his thirtieth year, single, and an artist. Of the twelve other men from Windham who at that time were eligible for military service, eleven of them—including Hapeman’s younger brother John—were each identified as “farmer.” The remaining man was listed as “laborer.” The compendium, formally titled “Consolidated List of all persons of Class I, subject to do military duty in the 13th Congressional District of New York,” does not specify what type of artist Frederick Hapeman was. In fact, while the “Consolidated List” is amply populated by farmers, laborers, mechanics, quarrymen, and even teachers—artists are few. The historical record is silent in regard to Hapeman’s artistic credo, nor does it offer much in the way of biographical information. Even the internet is reticent about him. Yet from the handful of facts that can be gleaned, it would be safe to say that Frederick F. Hapeman was a performance artist, of a certain sort.

Frederick F. Hapeman is but one of the many forgotten artists of the Catskill Mountains. We know he was an artist because that’s what he told the army captain who came through Windham, New York, in June of 1863 to register in a compendium the names of all men eligible for military service. The Civil War was raging. Fresh recruits were needed. The captain duly recorded for posterity the pertinent details of each man’s life: name; age; marital status; and profession, occupation, or trade. Frederick Hapeman was in his thirtieth year, single, and an artist. Of the twelve other men from Windham who at that time were eligible for military service, eleven of them—including Hapeman’s younger brother John—were each identified as “farmer.” The remaining man was listed as “laborer.” The compendium, formally titled “Consolidated List of all persons of Class I, subject to do military duty in the 13th Congressional District of New York,” does not specify what type of artist Frederick Hapeman was. In fact, while the “Consolidated List” is amply populated by farmers, laborers, mechanics, quarrymen, and even teachers—artists are few. The historical record is silent in regard to Hapeman’s artistic credo, nor does it offer much in the way of biographical information. Even the internet is reticent about him. Yet from the handful of facts that can be gleaned, it would be safe to say that Frederick F. Hapeman was a performance artist, of a certain sort.

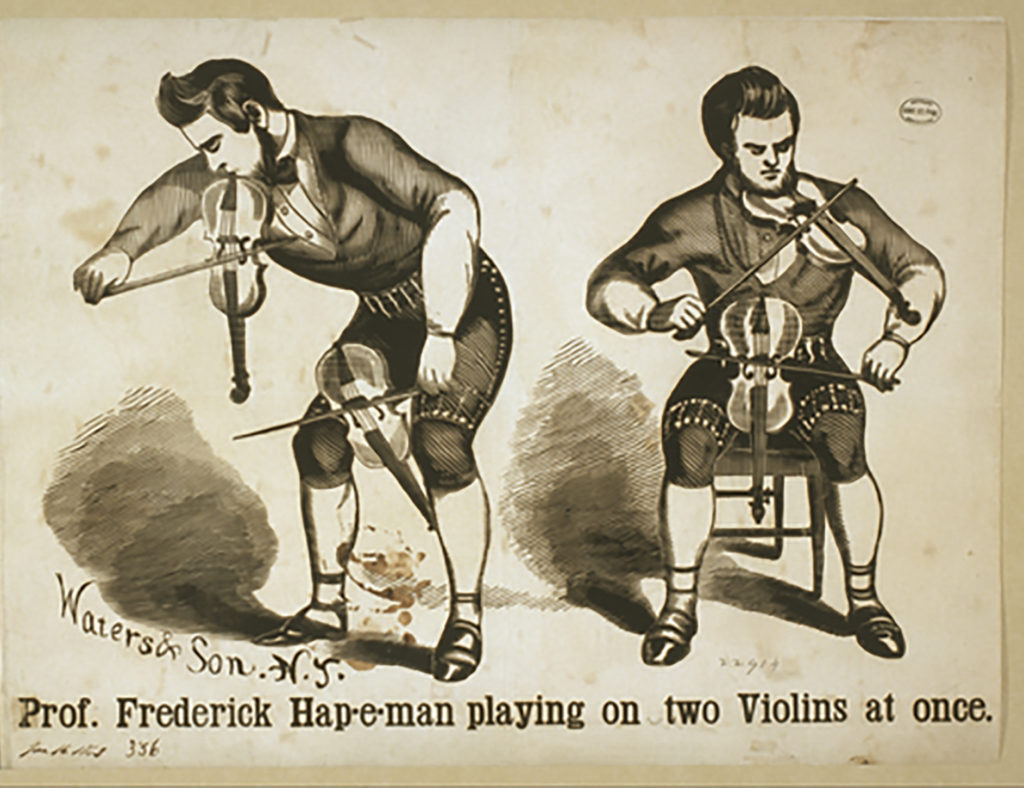

He was born on January 9, 1834, in East Windham, to Sally Newcomb and George Delmar Hapeman. He was the oldest of six siblings. Presumably they all grew up on the family farm. Years later, a writer for the Windham Journal observed that people in the area still recalled Hapeman’s “peculiarities.” He “has always been eccentric, yet we doubt very much but that he has always been able to judge right from wrong.” In 1860, Hapeman’s mother died. Not long after that he found hisway to New York City, where—thanks to a modicum of talent for playing violin—he secured employment with Phineas T. Barnum’s American Museum, at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street in lower Manhattan. At this point, he had adopted the stage name of “Prof. F. Hap-e-man,” a moniker he would continue to employ long after he left the stage. During his tenure at Barnum’s American Museum, “Prof. F. Hap-e-man” developed a repertoire of unusual musical “tricks,” including his signature piece: playing two violins at the same time. He was billed variously as “The Catskill Mountain Violinist,” “The Happy Fiddler,” “The Funny Man,” and—punning on his original name—“The Happy Man.” Interestingly enough, no supporting evidence or testimony to Hapeman’s sunny disposition has ever come to light. Just the opposite has been the case.

On February 22, 1863, Hapeman’s younger brother Robert—age 19—died while serving in the Union Army at Falmouth, Virginia. The cause of death—according to the Windham Town Clerk’s record of the men who served in the Civil War—was “typhoid fever.” Two months later, his father, George Hapeman died. He was laid to rest in the Peter Van Orden Cemetery in Windham, close by the grave of his wife, Sally, and son Robert. Two months after that, Frederick was registered as eligible for military service. And that is the last record we have of him in Windham.

Two years pass. “Prof. F. Hap-e-man” has become an inventor. He submitted something called “Golden Union Cement” for consideration at the Annual Meeting of the New York State Agricultural Society, where—according to their Proceedings—his invention received “favorable notice.” Over the next couple years, the “Professor” traveled around the state hawking his invention, taking out ads in local newspapers from Troy to Buffalo and south into Pennsylvania: “New Invention! Just the Thing! Prof. F. Hap-e-man’s Golden Union Cement, Only 10 Cents a Stick.” The larger display ads featured an illustration of a rather dour-looking Hapeman playing his fiddle. These ads suggest a grandiose business plan: “One Thousand Agents wanted to sell this cement. Great inducements will be offered. $500 worth may be carried in a satchel at once, or $35 worth in your pocket, it is so light for peddling.” At this point, the record of “Prof. F. Hap-e-man” grows ever more sketchy.

Sometime in the latter 1860s, Hapeman made his way into Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, where he met and proceeded to court a woman named Elizabeth Cobb. She was the second-eldest daughter of Adaline and James Cobb, Esq., prominent citizens of Greenfield Township. Much to her parents’ chagrin, Elizabeth accepted Hapeman’s whirlwind marriage proposal. Curiously, no formal record of this marriage has come to light. In 1871, Elizabeth gave birth to a son, named James, but he would always be known as “Jay.” By early 1872, Elizabeth had had enough of her husband. No specific details ever emerged, but as reported later that year by the Christian Cynosure newspaper out of Chicago: Hapeman “had used his wife so badly that her parents were compelled to take her to the paternal home for protection.” A Pittsburgh newspaper went further, asserting that Elizabeth had become “infatuated with, and finally married, a worthless fellow named Hapeman, much against the will of her parents. Like all such matches, this one proved most un-happy, and the daughter was in a short time forced to return to the roof of her parents, with little child.” For his part, Hapeman was not willing to let go. By mid-February he was in court in Carbondale, suing for custody of his son. As reported in the Scranton Republican, the trial took most of a week, largely due to Hapeman’s grandstanding: “The evidence taken was merely a resume of the Professor’s travels and numerous engagements in Barnum’s Museum and elsewhere.” Hapeman lost the case and, it would seem, his mind.

Sometime in the latter 1860s, Hapeman made his way into Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, where he met and proceeded to court a woman named Elizabeth Cobb. She was the second-eldest daughter of Adaline and James Cobb, Esq., prominent citizens of Greenfield Township. Much to her parents’ chagrin, Elizabeth accepted Hapeman’s whirlwind marriage proposal. Curiously, no formal record of this marriage has come to light. In 1871, Elizabeth gave birth to a son, named James, but he would always be known as “Jay.” By early 1872, Elizabeth had had enough of her husband. No specific details ever emerged, but as reported later that year by the Christian Cynosure newspaper out of Chicago: Hapeman “had used his wife so badly that her parents were compelled to take her to the paternal home for protection.” A Pittsburgh newspaper went further, asserting that Elizabeth had become “infatuated with, and finally married, a worthless fellow named Hapeman, much against the will of her parents. Like all such matches, this one proved most un-happy, and the daughter was in a short time forced to return to the roof of her parents, with little child.” For his part, Hapeman was not willing to let go. By mid-February he was in court in Carbondale, suing for custody of his son. As reported in the Scranton Republican, the trial took most of a week, largely due to Hapeman’s grandstanding: “The evidence taken was merely a resume of the Professor’s travels and numerous engagements in Barnum’s Museum and elsewhere.” Hapeman lost the case and, it would seem, his mind.

Just over two weeks later, on the morning of Friday, March 8, the not-so-happy man showed up at the house of his in-laws, seeking to take back his wife and son by force. And something terrible happened. The Scranton Republican provided the most detailed report of the many newspapers that carried the story. Hapeman, according to witnesses, “attempted to enter the house, but was met at the door by a brother of his wife, who refused him admittance.” Hapeman proceeded to dash in “a window and commenced shooting from a revolver into the room where his mother-in-law and others were, and hitting the former, who took refuge in the buttery. His knowledge of the house induced him to run around to the buttery window, which he smashed in and shot his mother-in-law dead.” Hapeman fled the scene but was quickly apprehended along the road and thrown in jail. The Scranton Republican account concludes on a solemn note: “It has produced great excitement, and a deep gloom rests over the neighborhood, where Esq. Cobb’s family are so highly esteemed. The fellow has been considered a nuisance for months, and now we shall be happily rid of him, although at a fearful cost to the many friends of the bereaved family.”

News of the brutal murder of Adaline Peck Cobb caught the interest of local newspapers back in Hapeman’s home region. On March 22, 1872, the Red Hook Journal offered a poignant albeit terse summary of this unhappy artist’s career: “Hapeman is well known in eastern Pennsylvania, and adjoining counties in this State, as Prof. Hap-e-man (happy man). He traveled with a store on wheels and could play upon two violins at once. He was looked upon as an eccentric character. He is in jail at Carbondale.”

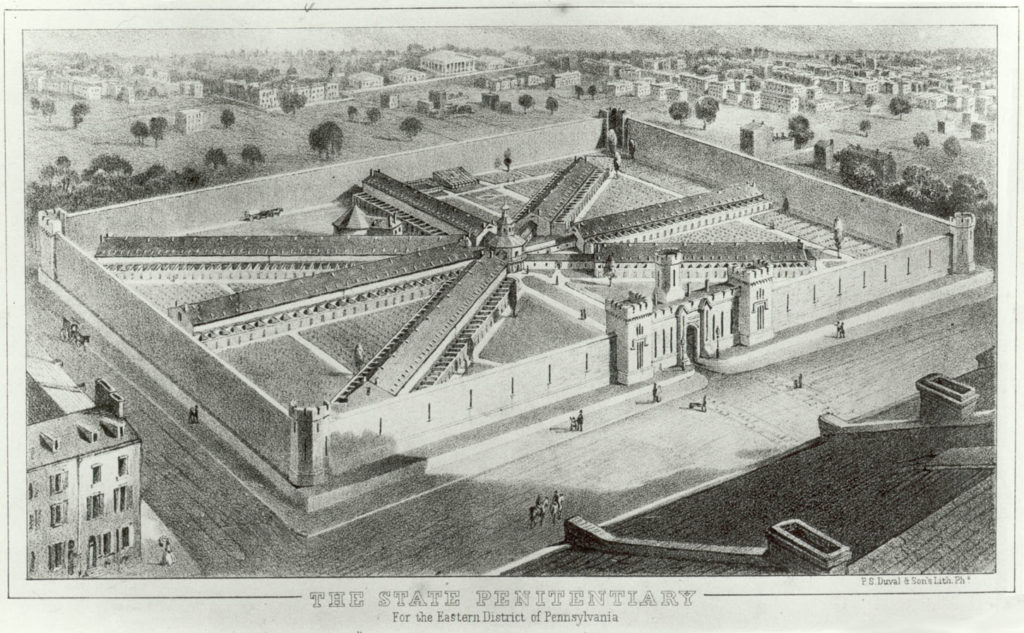

And in jail he remained until his trial in August, when he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to eleven years in the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. He served just over three years before succumbing to illness and dying in prison on October 5, 1875. He was forty-one years old. In the Registration of Deaths in the City of Philadelphia, his name is recorded as “Frederick Happimann.” He was buried in a nearby potter’s field known as City Burial Ground, a site later abandoned as a cemetery and converted to a city park. The hundreds and hundreds of human remains interred there were likely left in situ. The park today lies in ruinous neglect. As for the “occupation of deceased,” Frederick Happimann is listed in the Registration of Deaths as having been a “shoemaker.” May his soul rest in peace.

(Special thanks to Patricia Morrow, Town of Windham Historian, for the invaluable assistance she provided in hunting down the details of this story.)

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on April 12, 2019