The Old County Jail

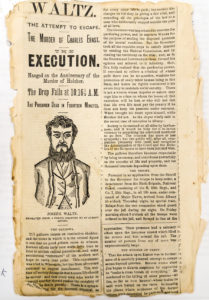

A steep, narrow street in Catskill, New York, leads to a dead end. There stands the former county jail, built in 1803. Long gone are the prison cells with their iron walls and bars and doors, yet the superannuated structure—with its thick walls and red bricks—still imparts a sense of impregnable authority. Over the course of the 19th century, four executions were conducted inside these walls, all by hanging. On May 1, 1874, a “stalwart farmer’s son” named Joe Waltz was put to death for the murder of an itinerant scissors grinder. His was the last hanging to take place in the county jail. In 1888 New York passed the Electrical Execution Act, and the state took charge of all capital punishment. After that hangings decreed by local governments fell by the wayside. By the early 20th century, the old jail had outlived its usefulness and a “modern prison” was built down the hill, behind the County Courthouse. It remains in use today, the oldest county jail in the state.

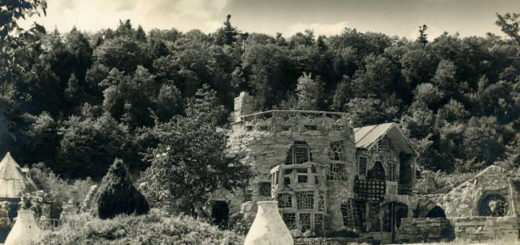

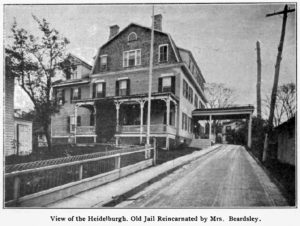

In 1909, the old jail building was sold to a Mrs. Beardsley for $3,000. She and her husband—a prominent architect—converted the structure into a hotel. They dubbed it the Old Heidelberg Inn. One might question the wisdom of repurposing a prison-house into a hostelry, but as local historian Frank A. Gallt rhapsodized in 1915: “In all, there is never a dream of the scissors grinder or the pitiful creatures that were for 112 years incarcerated in the mouldy smelling and vermin infested dark and repulsive cells. Preserved in the attic are chains, foot clamps and iron balls that were attached to leg chains, branding irons that tradition says were used on the very bad prisoners, padlocks, handcuffs with chains, all for desperate characters.” Despite the enticing upgrades made to the property, the Beardsleys did not fare well with their hotel business. After a few years they sold it, and the new owners had an equally tough go of it. By the late 1930s the building was shuttered and forlorn. People around town considered the place unlucky, perhaps even haunted. In later years it was converted into an apartment house and remains so today.

One might question the wisdom of repurposing a prison-house into a hostelry, but as local historian Frank A. Gallt rhapsodized in 1915: “In all, there is never a dream of the scissors grinder or the pitiful creatures that were for 112 years incarcerated in the mouldy smelling and vermin infested dark and repulsive cells. Preserved in the attic are chains, foot clamps and iron balls that were attached to leg chains, branding irons that tradition says were used on the very bad prisoners, padlocks, handcuffs with chains, all for desperate characters.” Despite the enticing upgrades made to the property, the Beardsleys did not fare well with their hotel business. After a few years they sold it, and the new owners had an equally tough go of it. By the late 1930s the building was shuttered and forlorn. People around town considered the place unlucky, perhaps even haunted. In later years it was converted into an apartment house and remains so today.

On the morning before he was to be executed, Joe Waltz—who for almost a year had been feigning insanity in the hope of having his sentence commuted by the governor—received word that no mercy would be forthcoming. His feigning immediately gave way to desperation. Later that very afternoon, he sprung at his jailer by surprise and bashed the man’s head in with an iron band. The jailer—who in fact was the constable credited with Waltz’s arrest—was a tall, quiet German immigrant by the name of Charles Ernst. He was said to be well-liked around town. According to the account published in the Catskill Recorder, Waltz then “dragged Ernst’s unconscious body diagonally across the floor into a corner out of sight, threw newspapers over the pools of blood, secured Ernst’s revolver and the key to the outer door of the cell.” Waltz was less than thirty seconds from “having a fair start for his liberty” when one of the sheriff’s children happened to spot what was going on and alerted the other officers, who were eating lunch at the time. They rushed in and seized the prisoner and returned him to his cell, this time in shackles. There he awaited his end.

On the morning before he was to be executed, Joe Waltz—who for almost a year had been feigning insanity in the hope of having his sentence commuted by the governor—received word that no mercy would be forthcoming. His feigning immediately gave way to desperation. Later that very afternoon, he sprung at his jailer by surprise and bashed the man’s head in with an iron band. The jailer—who in fact was the constable credited with Waltz’s arrest—was a tall, quiet German immigrant by the name of Charles Ernst. He was said to be well-liked around town. According to the account published in the Catskill Recorder, Waltz then “dragged Ernst’s unconscious body diagonally across the floor into a corner out of sight, threw newspapers over the pools of blood, secured Ernst’s revolver and the key to the outer door of the cell.” Waltz was less than thirty seconds from “having a fair start for his liberty” when one of the sheriff’s children happened to spot what was going on and alerted the other officers, who were eating lunch at the time. They rushed in and seized the prisoner and returned him to his cell, this time in shackles. There he awaited his end.

Next morning at the appointed hour, Joe Waltz was led from his cell and taken upstairs to a makeshift gallows below the jail’s prominent cupola. There he heard his death warrant read aloud in sonorous tones by his executioner, Sheriff Platt Coonley. As the reporter described it: “While this was being read Joe was standing up. He wrinkled his face and twitched his features, giving one of his growling cries like the roar of an angry beast. The Sheriff then asked: ‘Have you anything to say why sentence should not be executed?’ No response by word or look. The noose was then fastened to the rope. At 10:16 ½ the Sheriff pulled the cord, the weights fell, and the doomed man was jerked about four feet into the air, and then hung motionless.” Forty minutes later, the body was lowered and the coroner pronounced Joe Waltz dead of a broken neck.

Three days after that, Constable Charles Ernst died of the injuries inflicted by Waltz. Ernst’s funeral followed two days later. According to the newspaper: “There was an immense concourse of  people at the church. Rev. George A. Howard preached the funeral discourse. After the service the casket lid was removed, and the large audience filed by for a last look at the features of Charles Ernst. At the cemetery the last mournful ceremonies of the International Order of Odd Fellows were performed, and the body wad deposited in its final resting place.” Charles Ernst left behind a wife, three sons, and a daughter. The newspaper account concluded with these words: “Subscription lists have been left at the Tanners’ and Catskill Banks, for the relief of the bereaved family. We hope public sympathy will find substantial expression.”

people at the church. Rev. George A. Howard preached the funeral discourse. After the service the casket lid was removed, and the large audience filed by for a last look at the features of Charles Ernst. At the cemetery the last mournful ceremonies of the International Order of Odd Fellows were performed, and the body wad deposited in its final resting place.” Charles Ernst left behind a wife, three sons, and a daughter. The newspaper account concluded with these words: “Subscription lists have been left at the Tanners’ and Catskill Banks, for the relief of the bereaved family. We hope public sympathy will find substantial expression.”

As it turned out, the family—during this time of great trouble and sorrow—received little more than thoughts and prayers. Charles Ernst, respected as he was, had substantial debts. His creditors immediately came after his estate. Legal notices began appearing in the paper. All of the Ernst property was put up for auction. As the oldest son—fourteen at the time of his father’s murder—recalled sixty years later: “We had a fine set of ponies that I loved very much. . . . My father’s death threw my family into poverty as he had lived way beyond his means. I remember the ponies were sold at auction and it nearly broke my heart. All of my brothers and myself had to go to work. I was the oldest and went to work right away in the brickyards. I later had my own butcher shop. We got nothing from the town and my father had no insurance. It was a great struggle from then on for all of us to make our way in the world. But we did and we have come out all right.”

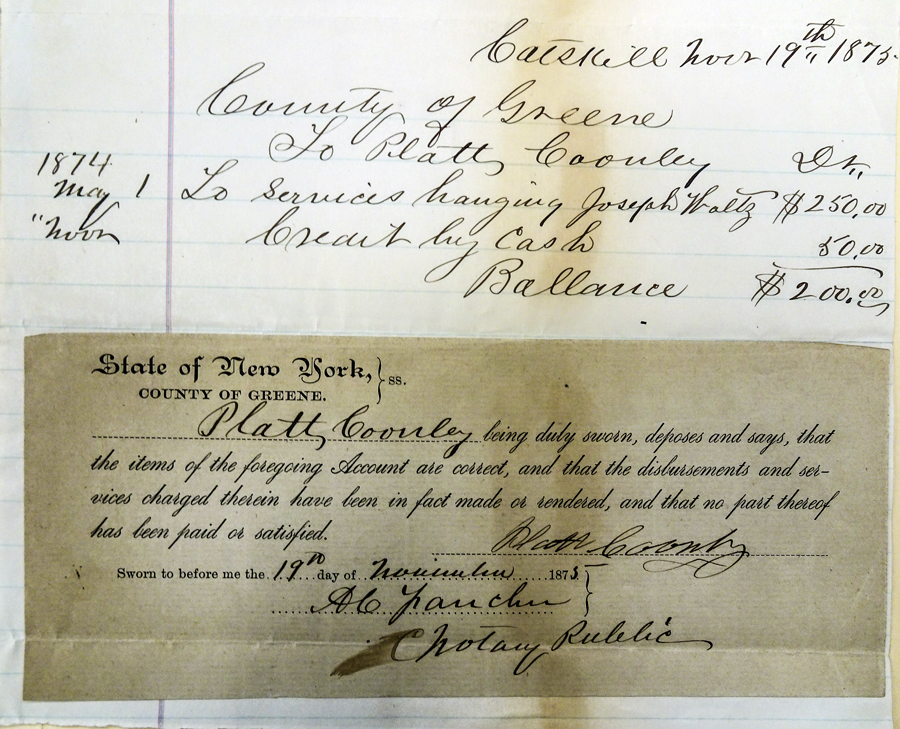

A year and a half after the event —in November, 1875—the County of Greene settled its final outstanding bill related to the matter of Joe Waltz’s execution. They issued a payment of $250 to Sheriff Platt Coonley for his “services hanging Joseph Waltz.”

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on April 6, 2018