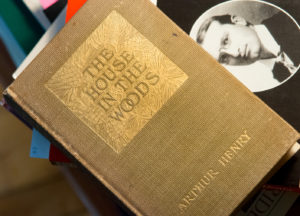

The House in the Woods

The Land of Rip Van Winkle is well-supplied with haunted houses. At least one of these places is the subject of a book. At the time of its publication—in 1904—no mention was made of any phantoms. Those came later. Perhaps the book itself is responsible for the haunting. After all, by its very nature a good story conjures up figments of the imagination. Who is to say with any certainty that the occasional chimera doesn’t break loose from the realm of fancy and take up residence in the so-called real world? Something like this seems to be the case with the memoir published by Arthur Henry titled The House in the Woods. The setting of both house and book is in the shadow of Roundtop Mountain, not far from either the old Tory Fort or the headwaters of Schoharie Creek. According to the back cover of the Black Dome Press edition published in 2000, The House in the Woods is “a deceptive memoir of the age-old quest for the ‘simple life.’” As historian Donald Oakes details in his lengthy afterword to this edition, when we look into the actual biography of Arthur Henry, “we pass through the Looking Glass into a world of unreality and distorted reality, into a world in which so often fiction became fact and fact fiction.” To anybody familiar with the Old Air of the Catskill Mountains, none of this should come as a surprise.

Briefly, The House in the Woods is the story of a youngish couple who, in seeking to escape the frenzied confines of the city, buy a plot of land in the wild wooly wags and build a house there. The main characters in this memoir are the author himself and his friend Anna Mallon, whom he refers to in the book as “Nancy.” They have a beloved collie by the name of Bob Go-Lightly, who makes unexpected appearances throughout the narrative, beginning with the opening sentence. The story takes place over the course of four years, from 1899 to 1903. Much of the book is concerned with the construction of the house and providing sketches of local people and their rural customs. Curiously, no mention is made of the couple’s marriage, which took place within that time frame—on March 8, 1903. Nor is any mention made of Henry’s previous marriage or the daughter who came of it. Also missing is any reference to finances, all of which were provided by Anna, who owned and operated a successful stenography business. Yes, the house was Henry’s dream but the dollars that built it were Anna’s. Oakes speculates she may have been the unacknowledged co-author of The House in the Woods, but that’s a truth only the dead would know.

According to his closest friend at the time—the writer Theodore Dreiser—Henry was “a dreamer of dreams, a spinner of fantasies.” But he was adept at putting those dreams into words. “It is difficult to keep awake in this sheltered spot,” Henry writes in the opening chapter of the book, fittingly titled “The Dream.” “A group of balsams break the chill west wind, but through their branches I can dwell with indolent eye upon the valley of the Plaaterkill. It is a far view, between unobtrusive mountain ranges, inclosing fields by the river, now green with the aftergrass, and little hills covered with timber.” As for the house itself, he writes: “Beautiful is our House in the Woods, and, though now a thing of timber and of stone, more beautiful than any wistful dream of it.” The structure was built with local labor, the “Neighbors” to whom Henry dedicated the book.

According to his closest friend at the time—the writer Theodore Dreiser—Henry was “a dreamer of dreams, a spinner of fantasies.” But he was adept at putting those dreams into words. “It is difficult to keep awake in this sheltered spot,” Henry writes in the opening chapter of the book, fittingly titled “The Dream.” “A group of balsams break the chill west wind, but through their branches I can dwell with indolent eye upon the valley of the Plaaterkill. It is a far view, between unobtrusive mountain ranges, inclosing fields by the river, now green with the aftergrass, and little hills covered with timber.” As for the house itself, he writes: “Beautiful is our House in the Woods, and, though now a thing of timber and of stone, more beautiful than any wistful dream of it.” The structure was built with local labor, the “Neighbors” to whom Henry dedicated the book.

The individualized portraits he provides of his neighbors are each a literary labor of love. For these alone The House in the Woods is well worth the read. Toward the book’s conclusion, the narrator observes: “Most of the young men I know here have been to New York, impelled by the vague aspirations of youth, and they have returned here of their own accord to live.” Among those young men is Will Dale, who laments: “The country is getting too greedy.” And John Gillespie, one year away from completing his studies at veterinary college, despairs that “there is so much sham and show and noise in the city, it wears you out.” And his brother Will, “an amiable giant, with clear blue eyes, penetrating and mild,” bemoans the sad state of American politics at the time: “I guess I’m not patriotic. I don’t sympathize with this country since the Spanish War. I can cut a good deal of wood in a day, but, still, I don’t seem to be strenuous enough for the life out there.” In the end, The House in the Woods is more about Henry’s neighbors—their generosity and hardworking way of life at the turn of the twentieth century—than it is about any city slicker’s “dream home.” The author himself recognized as much, expressing it in a concluding sentiment: “If we would live in our palace of dreams, we must do the chores.” It’s a lesson Henry learned from his unstinting neighbors on the Mountaintop, a lesson he hoped to pass along to his readers. “If I have succeeded in these pages, you must see, between each of these poetical statements, innumerable details of toil.”

But what about the ghosts? How did the House in the Woods become haunted? Donald Oakes details the subsequent history of the premises after the book’s publication. We learn that in “March 1905, the ink on the book hardly dry, their House in the Woods burned to the ground.” The house was immediately rebuilt, and again it was funded by Anna. The new house was constructed “not in replica but on the same foundations. It is this second House in the Woods that stands today.” The cost of rebuilding was high and put a strain on the couple’s finances. This combined with Henry’s larking about in the city with another woman put even greater strain on Anna Mallon’s well being. Through a complicated turn of events, the marriage eventually ended but not before Anna acquired full ownership of the house. She died out west in 1921, under mysterious circumstances, and the House in the Woods was passed along to her maternal niece. The property has remained in the same family ever since. During the course of his research in the closing years of the 20th century, Oakes heard tales from the latter-day owners that the house was haunted. “Well, every so often in the years we’ve had the House in the Woods, we’d be awakened in the middle of the night by the sounds of a man and a woman fighting. Shouting. The words were never clear, but the argument was vicious. It seemed to come from out on the lawn, but as soon as we’d turn on the floodlights, the sounds would stop—and there’d be no one there.” Oakes also reports that the ghost of Anna Mallon appeared in the house of a neighbor down the road.

1905, the ink on the book hardly dry, their House in the Woods burned to the ground.” The house was immediately rebuilt, and again it was funded by Anna. The new house was constructed “not in replica but on the same foundations. It is this second House in the Woods that stands today.” The cost of rebuilding was high and put a strain on the couple’s finances. This combined with Henry’s larking about in the city with another woman put even greater strain on Anna Mallon’s well being. Through a complicated turn of events, the marriage eventually ended but not before Anna acquired full ownership of the house. She died out west in 1921, under mysterious circumstances, and the House in the Woods was passed along to her maternal niece. The property has remained in the same family ever since. During the course of his research in the closing years of the 20th century, Oakes heard tales from the latter-day owners that the house was haunted. “Well, every so often in the years we’ve had the House in the Woods, we’d be awakened in the middle of the night by the sounds of a man and a woman fighting. Shouting. The words were never clear, but the argument was vicious. It seemed to come from out on the lawn, but as soon as we’d turn on the floodlights, the sounds would stop—and there’d be no one there.” Oakes also reports that the ghost of Anna Mallon appeared in the house of a neighbor down the road.

If nothing else, the House in the Woods certainly looks haunted, at least nowadays. The place seems to have fallen into desuetude. The forest is encroaching upon the meadow that had been carved out of it so many years ago. The shadows grow thicker with each passing year. Yet what Arthur Henry wrote about this place in 1904 still rings true: “In this particular spot there is a singular majesty even in its softest murmurs; for I lie upon the borderland between the world where God still reigns alone, and that portion of his domain which mankind has preempted—the wilderness and civilization, the unknown and the known.” One can only hope that those angry spectral voices that used to be heard coming from the lawn have at last found some peace. And maybe, just maybe, in that quiet, forgotten spot where the House in the Woods still stands, one might hear the distant, joyful barking of a collie welcoming somebody home.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on October 5, 2018