The Ghost of a Waterfall

This might be a fish story—you know, about the one that got away. Or it might be a tale of buried treasure. Either way, because it happened in the old air of the Catskill Mountains, it’s probably an example of both. Or neither. The spot where the events took place has long since vanished beneath the waters of the Schoharie Reservoir. Few alive today remember the name of this once-famous landmark. Yet Devasego Falls remains close by, just off the beaten path, submerged to the workaday eye. Here then is a story, construed from a sketchy historical record.

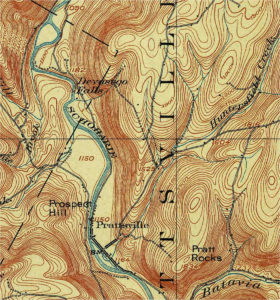

During the summer of 1892, the Reverend Charles Adams of New York City spent several weeks fishing in the vicinity of Prattsville. By all accounts, he was a most accomplished angler. A popular fishing journal of the day reported that “much of his time was devoted to whipping the sadly depleted trout streams within a few miles of the village, which, nevertheless, gave up to him between three and four hundred trout.” By the middle of September, he had turned his attention to black bass. These stocked gamefish were known to lurk in the large, deep pool just below Devasego Falls on Schoharie Creek, about a mile and a half north of the village. In those days, the falls were a popular tourist destination.

One dark, close night—because night, they say, is the best time for catching bass—the reverend stood fishing from a ledge not far from the summer-diminished trickle of the falls. From there he caught sight of a wondrous-large salmon, swimming near the shadowy surface of the pool. As the fish darted about in the dim waters, the reverend obtained a clear and indisputable view of something mysterious. The creature displayed an appearance unlike anything the veteran angler had ever seen before. More than three feet in length, the salmon’s body seemed more diaphanous than solid, pulsing with an unearthly, coral-colored luminescence. The improbable fish showed no interest in the reverend’s lure but did exhibit some puzzling behavior. “It looked up through the water and stared me right in the eye, piercing my soul with a devilish glare. I packed up my tackle forthwith and made haste from that ungodly scene.”

Rumors of a “ghost salmon” had been circulating in these parts for decades—ever since the early 1820s when a pair of mysterious strangers showed up at Prattsville and announced their intention to open a tannery next to Devasego Falls. They quickly had things up and running, but they kept aloof from the locals. Stories arose concerning the strangers’ odd habits—how they lived alone, never spoke to neighbors, paid for everything in Spanish silver coin, and ate nothing but the fish they caught from the base of the waterfall—fish, it should be acknowledged, that were looking increasingly unsavory since operations at the tannery had commenced. Strangest of all was the inexplicable sound of digging—metal clanging against rock—heard every night emanating from the depths of a remnant stand of hemlock above the tannery. Everybody wondered: What were those strangers up to?

The answer to this and many other questions did not arrive until more than a year later, when the tannery burned down under suspicious circumstances. The strangers remained in the area just long enough to collect a sizeable insurance payout. Then one night they disappeared. The next day, private security agents showed up in Prattsville, asking questions about the now missing strangers. Word spread that the two men were part of a brigand crew that had seized a trading vessel off Cape May. The buccaneers had made off with a sizable fortune belonging to the financier Stephen Girard, the Warren Buffet of his day. The mysterious strangers—now being referred to as the “Pirate Tanners”—were fugitives from the law. They had aided and abetted in murdering the ship’s captain with an axe and throwing the two mates overboard. Having taken possession of the vessel, the pirates steered it toward New York, only to get caught in a storm and shipwrecked on Coney Island. They all survived and even managed to salvage a chest full of coins, which they promptly buried on the shore and headed for the nearest tavern. There they proceeded to get drunk and shoot off their mouths about their recent exploits. The authorities were called in. Two of the pirates were captured and later executed on the island where the Statue of Liberty now stands. The authorities made their way to the spot where the chest was buried, only to find a gaping hole. The loot had been dug up and carried off by the pirates still at large. Among them, apparently, the two mysterious strangers who would show up in Prattsville a few weeks later.

The answer to this and many other questions did not arrive until more than a year later, when the tannery burned down under suspicious circumstances. The strangers remained in the area just long enough to collect a sizeable insurance payout. Then one night they disappeared. The next day, private security agents showed up in Prattsville, asking questions about the now missing strangers. Word spread that the two men were part of a brigand crew that had seized a trading vessel off Cape May. The buccaneers had made off with a sizable fortune belonging to the financier Stephen Girard, the Warren Buffet of his day. The mysterious strangers—now being referred to as the “Pirate Tanners”—were fugitives from the law. They had aided and abetted in murdering the ship’s captain with an axe and throwing the two mates overboard. Having taken possession of the vessel, the pirates steered it toward New York, only to get caught in a storm and shipwrecked on Coney Island. They all survived and even managed to salvage a chest full of coins, which they promptly buried on the shore and headed for the nearest tavern. There they proceeded to get drunk and shoot off their mouths about their recent exploits. The authorities were called in. Two of the pirates were captured and later executed on the island where the Statue of Liberty now stands. The authorities made their way to the spot where the chest was buried, only to find a gaping hole. The loot had been dug up and carried off by the pirates still at large. Among them, apparently, the two mysterious strangers who would show up in Prattsville a few weeks later.

What does all this have to do with the “ghost salmon” of Devasego Falls? Well, as any accomplished pirate will affirm, one never buries a treasure for the long term without installing a guardian to watch over it. The best guardian is thought to be the ghost of a human being who is killed on the spot and buried along with the treasure. Sometimes, though, the guardian can be an animal such as a cat, dog, or toad—or in this case, a salmon.

As it turns out, when the Pirate Tanners learned that Stephen Girard’s agents were closing in, they knew they had to make a swift departure. That meant going light, leaving behind their sizeable stash of silver to be reclaimed at a later date when things cooled off. Knowing that the hemlock forest—where up until now they had been burying and re-burying their chest in overly cautious fashion every night—would likely be the first place investigated, they resolved to stash the treasure where no one would think to look: At the bottom of the deep pool below Devasego Falls. The men loaded their money chest into the boat they had been using for fishing, rowed out to the center of pool, and as the cargo was about to be pushed overboard, one of the Pirate Tanners turned to the other and said: “Wait! What about a guard for the treasure? And stop looking at me like that!”

“Okay, okay,” said the partner. “How about this?” He held up the feculent corpse of a salmon, lifted from the bilgy floor of the boat. His fellow pirate nodded consent. The chest was pushed over the side, disappearing at once into the depths, followed by the toss of a ripe salmon and the gruesome slap it made when it hit the water. After that, the Pirate Tanners high-tailed it out of the area and—as far as can be established—never returned for their treasure.

Which is not to say others didn’t try to find it. Throughout the 19th century, hunting for pirate booty was a popular pastime. Many came to Devasego Falls of quest of the Pirate Tanners’ treasure, though none found it. If credence can be given to the tales, only a few of these seekers ever came close to success—and each of them in turn was scared off by the fishy guardian.

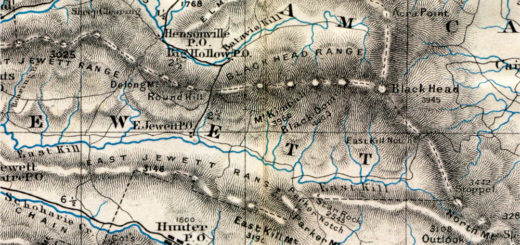

Alas, interest in the Pirate Tanners’ treasure fell off in the 1920s, after the City of New York built its dam down at Gilboa. The impounded waters of the Schoharie backed up nearly to Prattsville, drowning all the territory within reach. Devasego Falls and its deep pool now lie at the bottom of a pool deeper still. And it is there—if one might imagine—that their forms can still be discerned, pulsing in pale coral light that is alive.

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the March 16, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)