The Farm

On Saturday, May 27th, 1961, an estate auction took place on the Tryon farm just outside the hamlet of Norton Hill in the Town of Greenville. The weather that morning was unseasonably cold, gray, and showery. The mountains were shrouded in clouds but the apple trees were in full bloom. Birds may have been singing in the boughs, though hardly with any gusto. Parked cars and pickup trucks lined the muddy driveway leading up to the house. More vehicles were parked along the still unpaved town road bordering the pastures. A good-sized crowd of neighbors and many strangers—some huddled under umbrellas—had gathered in the yard in front of the century-old farmhouse. Its owner, Ezra Tryon, had died in the previous month. He was in his 80th year. Word is that his grandfather built this place in 1850. Ezra Tryon’s wife of nearly sixty years, Mercedes Moore Tryon, was still in the house while the auction was taking place. Over the course of that drab spring day, she witnessed the dispersal of all the farm equipment and household goods—chairs, lamps, throw rugs, pots, pans, dishes—that comprised the effects of a shared lifetime. Staying with her throughout that day was her fifty-six-year-old daughter, Violet. In 1930, she had married William Gedney of Greenville. Together they had two sons, William and Richard. Among family and neighbors in and around Greenville, young William was known by his middle name, “Gale.” He too was at the farm that day, to provide comfort and support for his bereaved grandmother. But he had an additional motive—he wanted to take photographs.

strangers—some huddled under umbrellas—had gathered in the yard in front of the century-old farmhouse. Its owner, Ezra Tryon, had died in the previous month. He was in his 80th year. Word is that his grandfather built this place in 1850. Ezra Tryon’s wife of nearly sixty years, Mercedes Moore Tryon, was still in the house while the auction was taking place. Over the course of that drab spring day, she witnessed the dispersal of all the farm equipment and household goods—chairs, lamps, throw rugs, pots, pans, dishes—that comprised the effects of a shared lifetime. Staying with her throughout that day was her fifty-six-year-old daughter, Violet. In 1930, she had married William Gedney of Greenville. Together they had two sons, William and Richard. Among family and neighbors in and around Greenville, young William was known by his middle name, “Gale.” He too was at the farm that day, to provide comfort and support for his bereaved grandmother. But he had an additional motive—he wanted to take photographs.

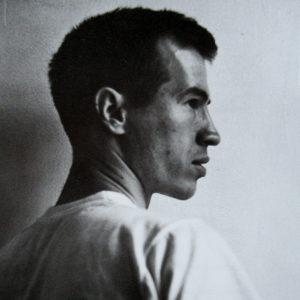

William Gale Gedney was one of the outstanding American photographers of the mid-twentieth century, yet few outside of a small circle of friends and  admirers recognized this prior to his untimely death. He was born in Albany in 1932. In his teens he was brought to Greenville, where both his parents had deep roots. His artistic talents were recognized early on. He graduated from Greenville Central School in 1951 and went on to attend the Pratt Institute in New York City. There he became interested in photography and chose to make a career of it. “It is continuously amazing,” he wrote in admiration of another remarkable photographer, “that this impersonal machine, the camera, should render not only the surface of the visible world, but is capable of rendering so sensitively the personality of the photographer.” By the mid 1950s, Gedney had embarked on his first major artistic project—a series of photographs documenting his grandparents’ life on the farm. This work occupied his creative energies for the next decade and more. At age twenty-six, he had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Over the years, he traveled with his camera across America and to India and Europe as well, compiling an extraordinary portfolio, consisting of pictures of everyday people acting out “the rhythms of unobserved lives.” His photographs were praised for their “distanced tenderness” and “elegiac simplicity.” He garnered numerous professional honors, including a Guggenheim, a Fulbright, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He taught photography classes at the Pratt Institute and Cooper

admirers recognized this prior to his untimely death. He was born in Albany in 1932. In his teens he was brought to Greenville, where both his parents had deep roots. His artistic talents were recognized early on. He graduated from Greenville Central School in 1951 and went on to attend the Pratt Institute in New York City. There he became interested in photography and chose to make a career of it. “It is continuously amazing,” he wrote in admiration of another remarkable photographer, “that this impersonal machine, the camera, should render not only the surface of the visible world, but is capable of rendering so sensitively the personality of the photographer.” By the mid 1950s, Gedney had embarked on his first major artistic project—a series of photographs documenting his grandparents’ life on the farm. This work occupied his creative energies for the next decade and more. At age twenty-six, he had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Over the years, he traveled with his camera across America and to India and Europe as well, compiling an extraordinary portfolio, consisting of pictures of everyday people acting out “the rhythms of unobserved lives.” His photographs were praised for their “distanced tenderness” and “elegiac simplicity.” He garnered numerous professional honors, including a Guggenheim, a Fulbright, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He taught photography classes at the Pratt Institute and Cooper  Union. His work was admired by luminaries in the field, including Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, and Lee Friedlander.

Union. His work was admired by luminaries in the field, including Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, and Lee Friedlander.

Despite demonstrating all this promise, Gedney’s career failed to take off. He never had another solo exhibition and no book of his photographs was published in his lifetime. His close friend Maria Friedlander, wife of photographer Lee, remembered how protective and careful he was about his work: “While he did bring it around to museums, magazines, galleries, and did find satisfaction in being exhibited, he was not persistent or aggressive if things didn’t work out, preferring instead to file it away and not enter into contention.” For reasons of his own, he chose to live in obscurity, eventually buying a house in Staten Island. In the mid-1980s, his health began to fail. In 1989, William Gale Gedney’s life was cut short by AIDS. He was 56 years old.

To return now to the farm, on April 25, 1967 Gedney wrote a letter to a potential sponsor describing a photographic project he had been working on for more than ten years. “I come from Greenville, New York. My grandparents on my mother’s side had a farm outside of Norton Hill. And they are what this is about. I photographed my grandparents in the last years of their lives. They stood for a way of life which is disappearing. They gave me tradition. They were the good, honest people who bother no one; live and die unremembered except by a few. I tried to put down a visual statement of their final years. As much as these pictures are about life on the farm, I think they are more about death.” Nothing apparently came of Gedney’s request, but the letter does provide a glimpse into what he was up to as an artist. The pictures he made of his grandparents’ last days set the stage for all his subsequent work. “I find a harmony in my grandparents’ lives, a peaceful settlement with their reality. Their surroundings and their existence are bound inseparable.”

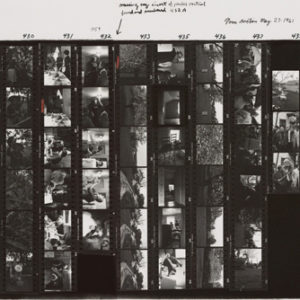

After his death, the entirety of Gedney’s photographic work was donated to Duke University. Included in the archive were 87 contact sheets filled with the pictures taken at the farm, pictures that he was sorting through, arranging and re-arranging, in order to make a “visual statement” about his grandparents’ lives. He never finished the project. As Geoff Dyer observes, this wasn’t the result of laziness but “of immersing himself so thoroughly in his work. He learned early on that everything undertaken for its own sake is worthwhile—irrespective of the outcome.” The outcome in this case might be described as a magnificent “might-have-been.” But to describe it in this way would be to commit an injustice. Gedney’s unfinished photographic “draft,” despite its sprawling lack of conventional narrative, is in and of itself a full and heartfelt response to a landscape all but vanished now from the Catskill region—a landscape and the lifeways that went with it.

this case might be described as a magnificent “might-have-been.” But to describe it in this way would be to commit an injustice. Gedney’s unfinished photographic “draft,” despite its sprawling lack of conventional narrative, is in and of itself a full and heartfelt response to a landscape all but vanished now from the Catskill region—a landscape and the lifeways that went with it.

Printed on one of the contact sheets from May, 1961 is a tiny image taken in the dining room of the Tryon farmhouse. Standing with their backs to the viewer and looking out the window—likely into the rain-soaked yard where the auction is taking place—are Mercedes Tryon and daughter Violet Gedney, the photographer’s grandmother and mother. What they see out that window has long since disappeared, just as what we now see in this picture has long since disappeared. The image emanates a profound sadness and indeed loneliness, but also something else, something that barely leaves a trace.

The Tryon farm was sold in September of 1961. Mercedes died the following year, one day short of the anniversary of her husband’s death. Violet died in 1995, at age 90, outliving her own husband by five years. Gale Gedney himself is buried with his parents in the Greenville Rural Cemetery. His photographs continue to render so sensitively the personality of the one who made them.

* * *

(Special thanks to Paige Ingalls and Don Teator for the help they provided me in my research for this essay.)

* * *

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on February 8, 2019