The Earle Farm

His name would have been forgotten by history, had not history shown up at his door. Moses Earle was a laconic farmer in the town of Andes, New York. He was born around 1781 and died in 1863. His father, Jonathan, a soldier in the Revolutionary War, brought his family to the thickly forested environs of the Tremper Kill in 1790. The elder Earle had clear title to one hundred acres on the lower slopes of Dingle Hill. The boy helped his father clear the trees and establish a successful farm.

When Jonathan died, Moses took over the farm and added to its size by leasing—for the sum of 32 dollars per year—an additional 160 acres from Charlotte D. Verplanck, an absentee landlord. According to one of the national journals of the day, she “was the owner of a few lots in great lot No. 39 in the Hardenburgh patent.” These “few lots” consisted of some 20,000 acres, a legacy of the old Dutch patroon system. She was one of several large landholders in the Hudson Valley and New York City who, in the mid-nineteenth century, were still profiting from an economic system charitably described as “feudal” in nature, less charitably as Northern sharecropping. Verplanck and her highbrow cohort derived their vast incomes from rents paid by toiling tenants who improved the lands but were denied opportunity to purchase them outright. This form of exploitation was absolutely legal, thanks to the powerful political influence wielded by the landholders. By signing the lease, Moses Earle joined the ranks of the disfranchised tenants.

He himself was a hardworking man. He continued clearing the forest and enhanced the value of his landlord’s property. Every year he paid his rent, right on time. In the words of the historian Henry Chapman, Moses Earle “was an Old School Baptist fatalist, who all his life had lived too close to wind and rain, storm and sun, to believe that God’s design could be changed.” Even so, by the early 1840s, Earle’s neighbors and many others across the region had adopted a far less accommodating attitude toward their inequitable situation. They rose up against the landlords in a series of protests—some comic, others tragic—that became known as the Anti-Rent Wars. On August 7, 1845, the most dramatic of those events took place at Moses Earle’s farm.

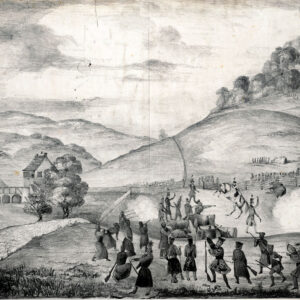

For more than a year, animosity had been building throughout Delaware County between those who opposed the lease system—the so-called “down-renters”—and those who defended it, the “up-renters.” The down-renters’ strategy was to encourage tenant farmers to withhold their rent payments. Despite some reluctance on his part, Moses Earle agreed to participate. Although he stopped paying the rent, he did hang on to the money just in case he was compelled to pay it. After two years, he owed Charlotte Verplanck sixty-four dollars in back rent. On July 29, 1845, the sheriff—a fellow named Green More—was dispatched to Earle’s farm to collect it. The sixty-three-year-old Earle refused to pay. That being the case, the sheriff was authorized to auction off Earle’s cattle on the spot. Advertising had gone up previously all across the county, but no bidders stepped forward that day. Apparently they were intimidated by the fifty or so down-renters who were standing close by, menacingly tricked up in calico dresses and wearing sheepskin masks. They called themselves “Indians.” That inspiration was derived from the antics of the Boston Tea Partiers of 1773. Sheriff More, having no further recourse to extract payment from the recalcitrant Earle, left the farm empty-handed.

Not one to be halted in the execution of his duty, the sheriff returned the following week. This time he was accompanied by Peter Wright, Charlotte Verplanck’s agent. In addition, More was expecting the arrival of his undersheriff—a short, hot-tempered, young fellow with red hair by the name of Osman Steele, who had been ordered to muster a sizeable contingent of reinforcements. Those extra men were going to be needed on that hot August day: by noon, more than two hundred masked “calico Indians” had swarmed onto Earle’s farm and surrounded the pasture where the cattle were to be auctioned.

Earle was presented with the same ultimatum: pay the back rent or his cattle would be sold off. At first, it seemed the old farmer was going to give in. He went inside his house to fetch his pocketbook. But as he was heading back outside, he was confronted by his foster daughter, Parthena Davis, herself a fervent down-renter. She snatched the pocketbook from his hands and shoved it into her bodice. Earle looked at her meekly, shrugged his shoulders, and returned outside. “You’ll have to sell,” he said to the sheriff.

By this point, Sara Earle—wife of Moses—was dispatching food out the kitchen door to feed the hungry “Indians” and Moses had brought out a pail of whiskey for them to pass around among themselves. The sheriff and Verplanck’s agent just stood there, agape and agog. “Where the hell is Steele?” they must have been wondering.

As it turned out, the undersheriff had been on his way from Delhi, though without the sizeable reinforcements his boss had requested. It was just Steele and a constable by the name of Edgerton—but to their credit they were riding a couple of formidable horses. Thirsty from their dusty ride, the two men stopped in at Hunting’s Tavern in Andes for a couple of drinks. When Steele was warned by the tavern’s sympathetic proprietor that a large number of “Indians” were lying in wait for him at Earle’s farm and that he had better be careful, the undersheriff made a dramatic gesture of dropping a bullet into his glass of brandy and proclaiming: “Lead can’t penetrate Steele!” He knocked back his drink and headed off.

In the meantime on Dingle Hill, tempers were rising along with the temperature. A ruckus was stirred by attempts on the part of the sheriff to move the cattle from the lower pasture to the road. At one point, the “chief” of the “Indians” brandished a crooked sword and pointed it at agent Wright, who in response pulled out a pistol. In swift fashion, the “chief” whipped out a pistol of his own. It was a standoff. The other “Indians” closed ranks around the agent and—as he explained in later testimony—commenced “blackguarding” him.

No surprise, then, at what happened when the two tipsy horsemen finally arrived on the scene around 2 in the afternoon. Agent Wright, feeling emboldened by the sight of the police officers, decided to press the issue, urging Steele and Edgerton to charge their formidable mounts into the pasture and prevent the “Indians” from further interfering with the sale of the cattle. The two men happily complied, the constable shouting: “The first man who offers to stop me from driving up the cattle, I will shoot dead!” He pulled out his pistol and seemed to be pointing it in the direction of the “Indians.” He fired. It’s not clear if his bullet found any mark. Somebody from the line of “Indians,” however, returned fire and did find a mark: the constable’s horse. As it fell, its rider was thrown to the ground, sustaining no apparent injury.

The ensuing moments were captured in an eyewitness account, which picks up at the first sound of gunfire: “I then said to myself, ‘I have been here long enough!’ and I ran out at the barway. If I should judge from the motions of [Undersheriff] Steele’s fingers, he fired twice and was in the act of firing the third time when he fell. As I was running toward the road I heard a volley by the Indians. I felt . . . it is no use to run further, for the balls could fly faster than I. During the volley Steele’s horse was shot. It turned its breast toward the fence, and as it was falling on its neck an Indian ran along the line, raised his rifle and fired. Steele fell over his horse’s neck mortally wounded.” Upon seeing his colleague downed, Sheriff More shouted: “For God’s sake, men, desist! You have done enough!” And with that, everyone in the pasture fell silent. Two horses lay dead on the grass, and Osman Steele sprawled writhing in pain.

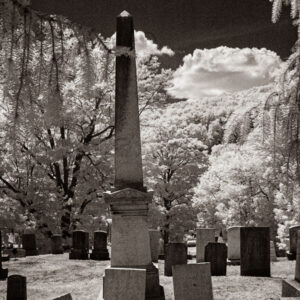

He was brought into Moses Earle’s farmhouse and put in a bed. A bullet had ripped through his bowels. He knew he was a dead man. “Oh!” he pleaded to the down-rent doctor attending him, “cut my throat and put me out of pain!” At one point, Steele looked up at Moses Earle, standing expressionless nearby the bed, and said: “Old man, if you had paid your rent there would have been none of this. I wouldn’t have been shot.” And Earle responded: “If you’d stayed home and minded your own business, you would not have been shot. I have paid rent long enough. Until I know what I pay it for, I shall pay no more if I can help it. If they will show me their title, I will pay every cent of the rent, but if they mean to bully me out of it, I will not pay if it costs forty lives.” Shortly after 8 p.m., in the wake of a blood-red sunset, Osman Steele died of his wounds on the bed of Moses Earle. A few days later he was buried with much fanfare on a high point of land in what would become Woodland Cemetery in Delhi. A grandiose monument was later erected on the gravesite. To this day, flowers are laid on the spot.

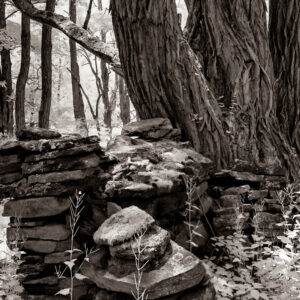

As for Moses Earle, his sharp words to the dying Osman Steele likely cost him a life sentence in prison. He was subsequently convicted—along with dozens of other men—of being an accessory in Osman Steele’s death. Fortunately for them, all those sentences were later commuted by the governor, but not before Moses Earle had spent two years in the state prison at Dannemora. By the time he was released and had gone home to his farm on Dingle Hill, the Anti-Rent Wars had concluded. The political tide had turned in favor of the down-renters, but Moses Earle chose not to take advantage of the new laws that permitted tenants to purchase their land outright. Instead, for the rest of his life he paid the annual rent of 32 dollars to the Verplanck family. He seldom left his farm and spent his days laying stone walls to bound off his hilly pastures.

In those final years, Moses Earle lived all by himself in the farmhouse he helped build. According to Alf Evers, the only company he kept was “a dog named Bruce and a squad of cats.” He died peacefully in his sleep at the age of 82, lying in the very bed where, eighteen years earlier, Osman Steele had died. Earle was buried with his father and the rest of the family in a small cemetery downslope from the farm toward the Tremper Kill. In 1930, all the family remains were transferred to a common grave in the Andes Cemetery. The monument there is dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Earle, revolutionary war soldier and “first settler in this part of Andes.” No mention of his son Moses.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on June 26, 2020