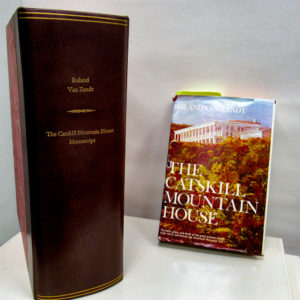

The Catskill Mountain House

In the summer of 1958, thirty-nine-year-old Roland Van Zandt—former U.S. Air Force bombardier, husband, father of four, and doctoral student of American history—was hiking in the vicinity of North Lake when he stumbled upon a many-chambered haunted house. The boarded-up, ramshackle structure was perched on an expansive ledge high above the village of Palenville. That location, if you trust the hearsay, is not far from the spot where Rip Van Winkle once upon a time ran into the nebulous crew of the Half Moon. “I was not expecting anything unusual that summer’s day while exploring some old trails 50 miles or so from my summer home in the Catskill Mountains. Nor when I first saw that scene did I suspect that my inner excitement forebode some new intellectual commitment that would occupy the next seven years of my life.” That “intellectual commitment” resulted in a substantial manuscript. Upon its publication in late 1966, The Catskill Mountain House—as the book came to be called—was immediately hailed as a classic.

In his review of the book, renowned theatre critic Brooks Atkinson expresses what might be described as the consensus view: “Being emotionally attached to this beautiful building and institution, Mr. Van Zandt has tracked down thousands of homely details throughout the 140 years [of the Mountain House’s existence], and charged them with personal feeling. No one can reconstruct the Catskill Mountain House but Mr. Van Zandt has recreated it. Although the Catskills have become a second-rate resort area, The Catskill Mountain House is a first-rate book—first-rate history, first-rate biography, first-rate folklore.” Well, if the Catskills today are once again something like a “first-rate resort area,” it’s no exaggeration to say that Roland Van Zandt’s book played—and continues to play—a significant role in the re-kindling of appreciation for this landscape and its history.

What then is The Catskill Mountain House about? According to advertising sent out by its publisher, “The volume tells the story of the birth, glory and death of the great Hudson Valley hotel which symbolized the American Romantic Era.” As described by Van Zandt himself in a discarded preface to the book, the hostelry “opened its doors in 1824 as a sumptuous 10-room ‘house of entertainment’” and by the latter part of the century had become “a monolithic 315-room palace, with miles of trails and carriage roads, two lakes, a 3,000 acre park, and its own railroad.” By the time of the Civil War, the Catskill Mountain House had become “one of the most expensive, luxurious, and fashionable resorts in all North America.” Those glory days continued right through the early 20th century, but the picture began to fade with the onset of the First World War. Demographic and technological changes—in particular, the automobile—brought about a slow decline in business. Nevertheless, the Mountain House each summer continued to welcome guests—though in ever-diminishing numbers—until wartime austerities forced the hotel to close for good in 1942. After that, the aged building stood in peeling desuetude for another twenty-one years. Then the State of New York acquired the property and burned the hulking remnants of the hotel to the ground in the icy pre-dawn hours of January 25, 1963.

Van Zandt was barely halfway through his work on the Mountain House project when the landmark was consumed by the flames. Yet he continued to labor away on the manuscript and finally delivered it to the publisher a couple years later. The high quality of the book’s production demanded extra time, so publication was delayed, but copies began to arrive in readers’ hands during the last days of December, 1966. The 416-page book is lavishly illustrated: 4 color plates, 85 black and white figures, 9 maps, four architectural floor plans, and an extensive bibliography. The dust jacket and frontpiece offer glorious reproductions of Sarah Cole’s painting Beach Mountain House, an 1848 copy of one of her brother’s canvases. The physical book itself has the heft of a work of art. It is handsomely printed and sturdily bound. On top of all that, The Catskill Mountain House is beautifully—indeed, hauntingly—written. As the venerable Carl Carmer writes in his Foreword to the book: “Hard work, imaginative research, patience, love, have given this writer a greater advantage than any magic dust on leveled walls can give.” Despite Carmer’s skepticism about magic dust, the book does exert a certain magical effect on many of its readers. Literary labor and high-end production alone do not account for this. Something else is going on.

When Van Zandt began his research, the Mountain House had been all but forgotten—and not just the Mountain House but also the surrounding, formerly famous landscape features that drew so many visitors in the 19th century: Kaaterskill Falls, Inspiration Point, Elfin Pass, Sunset Rock, Newman’s Ledge, the Bear’s Den, just to name a few. Thirty years later when he looked back on those early days of his investigations, Van Zandt recalled: “No one knew about the Mountain House. It was like being on an extended treasure hunt. The research was like pure gold, because no one had touched it. Finding the extinct old trails was just a great delight.”

Delightful as the experience of gathering information about the Mountain House was for him, Van Zandt the scholar found himself overwhelmed by the sheer volume of facts he had gathered. His original intention was to use this project as the basis for his dissertation in American Studies. For some years prior to this, he had been idly pursuing a PhD at the University of Minnesota. His mentor there was Mulford Q. Sibley, a popular teacher and prolific author, who wrote extensively on the subjects of pacifism, utopianism, and civil disobedience during the height of the McCarthy era. Van Zandt ultimately dedicated The Catskill Mountain House to him. In a letter to Sibley dated June 22, 1959, Van Zandt laments: “I still do not feel I have a subject. By absence of subject in the present instance, I do not know exactly what I mean. A certain density is lacking, both in regard to materials or data and ideas. It is true the subject still appears rich to me, extensively involved in the history of art and literature, etc. But something still seems lacking.” It took the academically-trained Van Zandt another few years to figure out exactly what his project was lacking.

On February 24th of the following year, Van Zandt was again writing to his mentor, this time confessing to having taken time off from his “Catskill Mountain project” because of a new interest. “I got deeply involved in photography,” he writes. “I have never before been so involved with people, and no doubt the experience was very exciting to me because of the previous years of lonely and rather fruitless scholarship. In all events, I had one of the happiest and most creative summers I have ever known. It was very strange to excel at something almost without effort, when the long-standing thing I had always put great store in—and great labor—had always had an opposite effect.” He was, of course, referring to his writing. Demand for his photographs started cutting deeply into his time, so for the sake of his Mountain House book he refused any more requests for pictures and returned to the writing. “But it was wonderful discovering the art of this medium, in coming into contact with people in this form—drawing upon something in my nature that for various reasons I could never put into my scholarship. I know now that my aesthetic and intuitive nature was spontaneously aroused by photography, and I cannot help having good feelings about the human response it aroused in both myself and my subjects.” This immersion into the practice of photography led Roland Van Zandt to see what his Catskill Mountain project had been lacking. He needed to put himself into the book.

And this he did by incorporating two dozen of his own photographs—almost all of them taken in 1961—as illustrations for The Catskill Mountain House. They caught the eye of fellow historian Alf Evers, who writes in his review that appeared in the Catskill Daily Mail: “Among the visual charms of the book are the very moving photographs taken by the author as the still glamorous old landmark tottered toward its doom.” Particularly moving for me are the photos used in the book’s final section, titled “Decade of Wreckage and Ruin”. These images serve to amplify the haunted and haunting quality of Van Zandt’s elegiac prose. “To be alone in the ruins of the Mountain House,” he writes of his own experience, “was to know how a giant building died. Silence filled the dry depths of the labyrinthine ruins like some fearful, unseen presence: it riffled the dust as you groped haltingly down the long dark corridor; it caught the loosened board by the unseen step; it ascended the untrod stairwell and waited expectantly in each empty room and chamber. And then, borne by the unseen wind, the silence suddenly materialized into a palpable threat of violence: in some distant recess of the lower building a door slammed with some more than human force. And that was all.” Yes, these words—along with the photographs taken by their author—capture something of the mute abandonment into which all compound things are ultimately cast. But something else is captured as well.

It was spotted by an old friend of Van Zandt, who wrote to him after reading the book: “I want to share with you the most striking immediacy of the book for me personally—and it may surprise you completely—and this, Roland, revolved around a very simple thing perhaps—the night you stayed in Mountain House to capture the feeling of dawn’s wonderment. This expressed to me your genuine ‘call’ to commemorate the House and it felt as if I were there to share the experience with you. All I remember of you is caught up in this one experience alone, it seems. It was you. It is you. If I write more at this point, I know I will spoil whatever effect I wish to achieve.” I like to think that the author of The Catskill Mountain House was delighted to receive this letter.

I myself never met Roland Van Zandt, but discovering his book in the public library when I was fifteen years old altered the course of my life. I see that now—even if this little essay is all I have to show for it. Back then, The Catskill Mountain House was just another one of my literary obsessions—along with the dog stories of Albert Payson Terhune, the eco-political rantings of Henry David Thoreau, and the spooky, biting novels of Shirley Jackson. I pursued these interests with the greatest of passion. But I admit, sometimes I did pause to doubt, especially when somebody asked “Why are you spending all your time on that?” Might there be something lacking in these interests of mine? After all, it’s not like a love for literature—or for history, or for places, or for art—prepares anybody for a career in the America foisted upon us by the news and the words of politicians. As I open up my well-worn copy of Van Zandt’s fine book, the first thing I see is my name on the inside cover—rendered in the block print letters of a fifteen-year-old. It took the loss of his ostensible subject—an old hotel gone up in smoke—for Roland Van Zandt to discover his true subject. I look into his book now and discover that we share the same object of study.

* * *

(Special thanks to Jonathan Palmer, Archivist at the Vedder Research Library. All photos by Roland Van Zandt courtesy of the Vedder Research Library.)

* * *

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on March 1, 2019