The Brief, Adventurous Life of Nelson J. Scribner

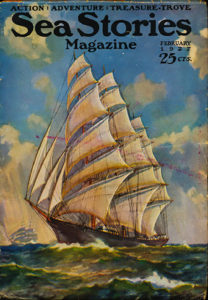

The literary remains of writer Nelson J. Scribner (1899-1926) are not extensive. His published work consists of one story—“The Luck of Lucky Joe”—which appeared posthumously in a pulp fiction magazine in 1927. Copies of that once-popular periodical—called Sea Stories Magazine—are all but impossible to find nowadays. Other than that one story, the only surviving work by Scribner is a brief, unpublished autobiography, written in 1925 for an English class he was enrolled in at the University of Florida. The nine-page transcript, yellowed with age, is archived at the Vedder Research Library in Coxsackie. Scribner begins his life story with an apology of sorts: “It is hard for me to write about myself, and the reason for this is that there is not much to tell. I have always been interested in people and what went on about me, and this has led me to play the role of spectator a great many times and view happenings in which I did not take part. If I digress it is because other things seem more important than what I myself was doing at the time, and perhaps these things had a bearing on what I did thereafter, and so in the end affected me as well.”

The literary remains of writer Nelson J. Scribner (1899-1926) are not extensive. His published work consists of one story—“The Luck of Lucky Joe”—which appeared posthumously in a pulp fiction magazine in 1927. Copies of that once-popular periodical—called Sea Stories Magazine—are all but impossible to find nowadays. Other than that one story, the only surviving work by Scribner is a brief, unpublished autobiography, written in 1925 for an English class he was enrolled in at the University of Florida. The nine-page transcript, yellowed with age, is archived at the Vedder Research Library in Coxsackie. Scribner begins his life story with an apology of sorts: “It is hard for me to write about myself, and the reason for this is that there is not much to tell. I have always been interested in people and what went on about me, and this has led me to play the role of spectator a great many times and view happenings in which I did not take part. If I digress it is because other things seem more important than what I myself was doing at the time, and perhaps these things had a bearing on what I did thereafter, and so in the end affected me as well.”

Nelson Scribner was born in December of 1899, where exactly is unknown but likely in either Haines Falls or the village of Catskill. His great-great-grandfather was Silas Scribner (1765-1844), who early in the 19th century acquired a large tract of forest land on South Mountain, which included Kaaterskill Falls and the Pine Orchard. “The first thing I remember seeing were mountains,” Nelson writes. He goes on to provide an account of his family’s history. “My great-great-grandfather came up into the then wilderness, built a sawmill, and began cutting timber and sawing logs. He passed on and left his mill. Each succeeding male member of the family continued cutting timber and sawing logs until they became fairly well established in the business. I suppose I might have been cutting timber and sawing logs, too, except for the fact that the sawmill burned down about the time I was born, and the timber began to give out shortly after I was born. Then, about this time, a forest fire destroyed all the timber on a mountain where most of our land was located.” Scribner is referring to the infamous conflagration of August, 1900, which raged for several days across South Mountain, consuming hundreds of acres and claiming the life of a young man by the name of Frank Layman. Scribner continues: “I don’t remember the fire, but I remember the results of it, and how the mountain looked long after the fire had swept it bare of living things.” He describes the fire-ravaged slopes below Kaaterskill Falls: “You could stand opposite it and look across the gorge and see the mountain-side barren of all life, with the charred trees standing stark and ghost-like and utterly lonely. A forest of trees, but of trees that were dead.” The author here is setting both the tone and theme for the rest of his memoir—wistful melancholy in the wake of paradise lost.

Scribner was recalling these events fifteen years after the fact and far away from the Catskill Mountains. He recalls the golden days of youth, when he spent most of his spare time fishing and tramping about in the woods. “I knew all the streams and lakes thereabouts, especially one called Spruce Creek, in which I angled persistently for small brook trout and minnows. I followed it for miles until it became lost in a maze of little streams. I used to long for those mountains after I left them. I am going back there some day and see if that creek is still there.” He also writes of “a certain cliff not far from our home”—perhaps the same one from which Natty Bumppo fancied he could see “all creation”—where, in Scribner’s words, “mountains did not shut out the view.” He effuses over the remembered vista of the Hudson Valley and its farmlands, a huge checkerboard “of green or yellow that varied in color as the seasons changed. Beyond these the waters of the Hudson caught the sun’s rays intermittently, and still farther beyond, the blue haze which hung over the valley sometimes lifted enough for one to distinguish some hills backed against each other, and showing dimly in the distance.” After mentioning that his mother was also fond of this view, Scribner concludes his catalog of halcyon days: “I wondered what was beyond those hills, and down the river.” To him the Hudson seemed the very River of Time.

Nelson Scribner’s memories of his Catskill Mountain childhood take up only a couple pages in his autobiography. He left Haines Falls at age ten or eleven, when his family moved to the Florida Keys. The remainder of the manuscript recounts a few memories of growing up in Florida, including a description of the old sponge-fishermen he met, who showed him how “to throw a cast net, and how to scull and steer. They showed me where the crawfish lived in the rockholes, and how to rig lines for snappers, and grouper, and barracoota.” He describes how “in Key West harbor the masts were thick, and the sponge market was a busy place. It is not so now. The white sails have gone, and most of the old spongers and fishermen have gone too. There seems to have been a class of those old-timers who all went out together, and no one can take their place.”

Scribner had arrived at Key West in time to witness the final leg of the Overseas Railroad being constructed. “That work interested me as much as anything I know, not only the work itself, but the men who did the work. In the railway construction camps were represented all the nations of the world. . . . Former army, navy, college, and prison men and just plain wanderers, all drawn together by the magnet which was the railway.” One of these fellows—his arms and shoulders “splashed with tattooing”— had spent his life wandering the world on tramp steamers. “He showed me how to make knives and fishhooks from files.” But that man, like so many others, did not remain long. “He never stayed anywhere long. He was gone one day, and I never saw him again. I often wondered what became of him.” Another man working on the railroad construction—“one Patrick Something”—was an Irishman, who every week wrote a letter “to a mother in far off Donegal.” He told young Scribner that he had been away from home for many years but would return there as soon as he saved a little money, “for the old mither is wantin’ me bad ye see.” But the poor Irishman met with a gruesome accident, struck by a concrete bucket and knocked dead. “They buried him on one of the keys not far from the railway, and his grave would be hard to find now for the vines are thick there. So Patrick never returned to Donegal.” Construction of the railway was completed in 1912, “and the camps were torn down, and the big machines . . . were sold and the men who manned them scattered and were gone no one knew where.”

In 1917, the United States entered World War I. Scribner had just finished high school and was planning to go to college. Instead he went into the Navy and served for two years on a sub chaser. The most evocative section in the autobiography concerns the years immediately after the war. Scribner observes that for many of the men who returned to civilian life “things didn’t go quite so well as was expected.” Things had changed, “and not the least of these were those in the men themselves. A feeling of vague dissatisfaction was in the air. A great many found, on checking up, that there were numerous places they had missed seeing.” A great restlessness seemed to be taking hold in America. A large number of the men who served in the war had now come to the conclusion “that there was no place quite so distasteful as the one in which they were.” Still others “had a vague idea of wanting something, and wanting to be somewhere, but just what they wanted or where they wanted to be they did not know.” As for Nelson Scribner himself, “I had a feeling that I was long overdue at some remote place.” One day he just up and quit his job as a clerk, “with almost no notice at all.” He signed on with a naval vessel and stayed with it for more than a year, until getting “paid off” in California and working his way back to Florida. In Jacksonville he enrolled at the University and came to write his autobiography.

I have read and re-read Scribner’s manuscript many times since I happened upon it earlier this year while looking for something else at the Vedder Library. The matter-of-fact plaintiveness of Scribner’s writing style is haunting. Nowadays when I am in the vicinity of Kaaterskill Falls—and especially when bushwhacking along Spruce Creek in the ghost-flowered course of its upper reaches on North Mountain, where it loses itself in “a maze of little streams”—I think of that young man who loved this place and longed so deeply to see it again. He never did. In the same library file that contains the manuscript of his autobiography, one finds a bill from Riverside Hospital in Jacksonville for a six-day stay in October, 1926 (“Operation: $200.00”), another bill from the W.L. Philbrick Funeral Home in Miami (“Opening & Closing Grave: $10.50”), and several death notices clipped from various newspapers (“Funeral services for Nelson Joseph Scribner, 26, World war veteran and student of the University of Florida, who died on October 28, 1926, in Jacksonville, will be conducted at 2:30 p.m. today in Woodlawn Park cemetery.”). The file offers no information regarding the cause of death.

Nelson Scribner was born in the same year as Ernest Hemingway, another writer who acutely felt that same postwar bewilderment and restlessness. Hemingway lived for decades after the war, writing many books, and was awarded the Nobel Prize. Ultimately, though, he took his own life—whereas Scribner’s ended abruptly due to an unspecified illness. He did not even live long enough to see his first publication. For the last many months I have been trying to track down a copy of that magazine so I can read the story, but without success. Tempting as it may be to count Nelson Scribner’s life among those great “what ifs” and lament the loss to literature, some succor can be found in the closing words of his autobiography: “When I left home in 1917 I wanted to see some adventure. I had heard and read of it a great deal, maybe a little too much. On looking back it seems that I skirted the edges of adventure a good many times without crossing its borders. Perhaps it was there at other times and I did not see it. I may have been in it and did not know it, but plots in life do not unwind as they do in stories—you only catch glimpses of them here and there.”

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 23, 2019