Saint Mary of the Mountain

The old cemetery sits on a small rise above the highway just east of the village of Hunter. Well over a century has passed since the last interment. The monuments—some of which are still standing, others toppled, shattered, and dislocated—are inscribed with names mostly Irish in origin: McGuinness, O’Kelly, Carr, Gillespie. On a warm August afternoon, clouds lofting over Colonel’s Chair cast picturesque shadows across the ski slopes. Along the highway, a steady stream of vehicles come and go. Mostly go. None stop. The air in the cemetery is fragrant with wild thyme—Thymus serpyllum—mats of it blooming abundantly between the markers. “All flesh is grass,” they say, but here, in the churchyard of Saint Mary of the Mountain, it is thyme. As for the church itself—despite what the internet might say—the structure no longer stands. Just last year it collapsed in upon itself, after decades of neglect. Only the stones remain—those of the front steps and those in the burial ground. The rest of Saint Mary of the Mountain has been lost to time.

Saint Mary of the Mountain was the oldest Roman Catholic church in the Catskill Mountains. It had been established in 1839 to serve the large number of Irish (and some German) immigrants who came to Hunter to work in the lumber and tanning industries, which during the mid-nineteenth century were booming. In October of that year, the cemetery was laid out and work commenced on putting up the church building, a modest edifice measuring 20 by 30 feet. It was constructed from hemlock and basswood trees cut on the site. Work was completed by the following summer and the new church opened its doors to parishioners on June 23, 1840. Even before the first mass was celebrated, the first burial took place—three-year-old Catherine Anne Lackey. No monument today indicates her grave.

who came to Hunter to work in the lumber and tanning industries, which during the mid-nineteenth century were booming. In October of that year, the cemetery was laid out and work commenced on putting up the church building, a modest edifice measuring 20 by 30 feet. It was constructed from hemlock and basswood trees cut on the site. Work was completed by the following summer and the new church opened its doors to parishioners on June 23, 1840. Even before the first mass was celebrated, the first burial took place—three-year-old Catherine Anne Lackey. No monument today indicates her grave.

Prior to the arrival of forest industry, Hunter must have been a howling wilderness. At least that’s how town historian Edwin C. Holton presented it in his 1884 account published in Beers’ History of Greene County. “The deep, dark and widespread forests, the rough mountain cliffs, the wild ravines, gorges, and caves of the mountains in Hunter, have been from time immemorial a chosen and favorite resort of lynx, panthers, wolves, bears, deer, and large venomous snakes.” It’s surprising that anybody would want to travel through such ferocious wooly-wags, much less choose to live there. But one goes where the work is. Immigrants showed up in droves, and with them came their merry-making ways. Hunter became a lively place—much livelier than the Hunter of Holton’s day, which was under the heady influence of the temperance movement. “Old settlers,” he writes in his sly fashion, “affirm that spirits ran as free then as now; now before the bar; then very free from behind; in fact every other house sold rum, cherry-brandy, and cider; that they have seen a dozen men in one grand knock-down fight, in the manner of an old-styled ‘ring-wrastle.’ Of course this was due to the foreign element engaged in lumbering and tanning.” Oh that pernicious foreign element—keep your eye on it! “But the evil of intemperance,” Horton concludes, “was then unnoticed by press and even pulpit. Temperance among the best men consisted in not getting drunk, but a little boozy.” Boozy as they were or seemed, come Sunday morning the foreign element filled the pews at Saint Mary of the Mountain.

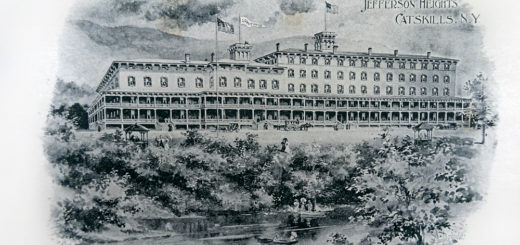

The good times for both village and parish came to an end soon enough. By the 1870s, the parish of Saint Mary of the Mountain was in decline. “It was a troubled period,” writes church historian Father Daniel Nusbaum, “because the mountains had nearly been denuded of hemlocks, and a new chemical process was replacing the old tanneries. Many families moved out, and the great tanneries fell into ruin.” Bad times, too, come to an end. In this case, thanks to the arrival of the railroad in Hunter in 1882. This led to a surge of summer visitors that “brought life back to the moribund parish of Saint Mary of the Mountain.” A boom in hotel and boardinghouse construction followed, which in turn drew new waves of Catholic laborers and their families to the Mountaintop. By 1884, according to one railroad summer guidebook, 11,270 beds were available for visitors to the area. This marked the beginning of a long period in which a rapidly expanding urban middle class began to enjoy the luxury of a couple weeks “in the mountains,” a privilege previously enjoyed only by the most wealthy. Thus the beloved American summer vacation was born.

The good times for both village and parish came to an end soon enough. By the 1870s, the parish of Saint Mary of the Mountain was in decline. “It was a troubled period,” writes church historian Father Daniel Nusbaum, “because the mountains had nearly been denuded of hemlocks, and a new chemical process was replacing the old tanneries. Many families moved out, and the great tanneries fell into ruin.” Bad times, too, come to an end. In this case, thanks to the arrival of the railroad in Hunter in 1882. This led to a surge of summer visitors that “brought life back to the moribund parish of Saint Mary of the Mountain.” A boom in hotel and boardinghouse construction followed, which in turn drew new waves of Catholic laborers and their families to the Mountaintop. By 1884, according to one railroad summer guidebook, 11,270 beds were available for visitors to the area. This marked the beginning of a long period in which a rapidly expanding urban middle class began to enjoy the luxury of a couple weeks “in the mountains,” a privilege previously enjoyed only by the most wealthy. Thus the beloved American summer vacation was born.

For the next many years—well into the twentieth century—Saint Mary of the Mountain prospered, largely due to summer visitors. But following World War II, things began to change once again. Highways replaced railroads, air conditioners made summers in the city more bearable, and cheap and efficient air travel to exotic destinations worldwide drew vacationers away from the Catskills. As John Ham explains it in his afterward to Father Nusbaum’s history: “Since the late 1960s, the Northern Catskill region has undergone a transformation from a hotel centered resort area with travelers arriving and staying for the season in large summer hotels and boarding houses, into a major ski and winter sports area catering to a younger and more mobile generation.” The old hotels and boardinghouses fell into decay. Many of them burned to the ground. Their names and locations are falling out of living memory.

Sadly, Saint Mary of the Mountain met a fate in kind. Sunday attendance fell off. Fewer and fewer masses were said in the church. Maintenance of the building was neglected. Despite a significant refurbishing in the 1960s—including a new foundation, new stained-glass windows, and a fresh coat of paint—the old wooden studs in the walls, riddled with termites and rot, were not replaced. Thus the slow, sad work of decay was allowed to continue over the next decades, until one fine morning in early April 2017, oblivion claimed yet another venerated Catskill Mountains landmark.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 24, 2018