Resorts of the Catskills

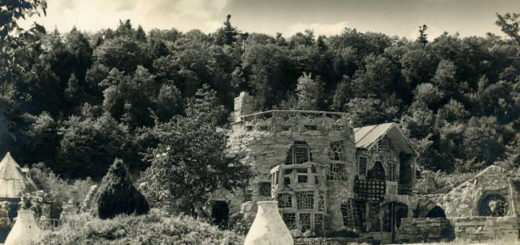

He showed up in Windham—with his camera—sometime after Labor Day in 1977. That was the time of year he preferred to work. Most of the summer vacationers were back home by then, at their jobs or in school. The weather on the Mountaintop that week was glorious, as it so often is in September. The trees were on the verge of autumn color. The sky was cloudless. “I only photograph under blue skies,” he often said. Blue skies and early morning sun. “I love the light at that time of day. It’s like golden syrup. Everything is fresh and no one is there to bother you.” John Margolies spent the next week photographing many of the old family resorts that were still operating along the Batavia Kill, including the Sugar Maples, the Osborn House, and others not yet shuttered for good. With his trusty Canon camera mounted with a no-frills 50mm lens, he shot several rolls of film. He liked to use Kodachrome ASA 25 because it insured “maximum color saturation.” Two years later, a small selection of these photographs was published by the Architectural League of New York in a book titled Resorts of Catskills. To look at Margolies’s pictures today induces in the viewer a pleasant albeit unsettling melancholy. It’s like strolling around the outside of a haunted house and peeping in through the windows.

John Margolies (1940-2016) is best known as the photographer who popularized the vernacular commercial architecture of roadside America. He did so in a series of books extending over three decades. His favorite subjects were the mom-and-pop gas stations, restaurants, movie theaters, motels, theme parks, game farms, mystery spots, miniature golf courses, signage, and vacation resorts that added singular color to the American landscape before interstate highways and air travel erased them from the map. Margolies had a passion for architectural barbarities. Where others saw kitsch, he observed neglected beauty. “Yes,” he rebuked one interviewer, “call it kitsch if you must. But I really don’t enjoy that word. ‘Kitsch’ was invented by intellectuals—as an excuse for not thinking about something.” Recognition for his work was slow in coming, yet his perseverance paid off. An architecture critic noted that Margolies “has led dozens of his colleagues toward an appreciation of those buildings that might be called the exclamation points of the landscape.” And according to Smithsonian magazine, his work “has helped preserve a portion of our common heritage by documenting thousands of buildings, many of them just months or even days before the bulldozers were to carry them away for good.” Nowhere is this more true than in the Catskill Mountains.

Resorts of the Catskills includes just sixty-three of the many thousands of photos that Margolies took throughout the region during the mid-1970s. And only five of those included in the book were from the Windham shoot. But many more can now be viewed online thanks to the Library of Congress. The John Margolies Roadside America Photograph Archive housed there includes 11,710 color slides acquired directly from the photographer, the core of what he “considered the exemplary images of his subject matter.” Indeed, they are. Over the last week, I spent hours perusing the more than 1200 images that came up when I searched the archive using the term “Catskills.” Mostly, though, I focused on the pictures taken in my neck of the woods—Windham—because gazing at these images was like stepping back into the place as it appeared when I was growing up. Or at least how certain landmarks appear in my memory: the Sugar Maples Resort, Nielsen’s Lodge, the Orchard Grove House (Kallithea), and the Osborn House. All of them are either vanished, in various stages of decay, or metamorphosed into unrecognizableness. The artifacts of leisure—the resorts, the handball backboards, the shuffleboard courts, the swimming pools—are quickly swallowed by oblivion. As historian Elizabeth Cromley expresses it in an essay included in Resorts of the Catskills: “Many period carcasses dot the hillsides today, succumbing to weeds and waiting for fire.” The book—long out of print—stands as a monument to the passage of time.

Few of the venerable resorts photographed by Margolies remain in operation. Among them is the vibrant Thompson House in Windham, which opened its doors to guests in 1880 and is now in the seventh generation of management by the same family. Margolies must have been quite taken with the place, as the Library of Congress archive includes thirty-four pictures he took there during his 1977 visit. One in particular stands out for me. It was snapped on the porch of the Pines Inn, an older hotel that was incorporated into the Thompson House operations in 1958. Sitting in chairs, relaxing on the porch, are a dozen or so guests, mostly women, in their seventies and older. Another half dozen or so are standing, chatting. Seated in the middle are two women enjoying a good laugh. The man sitting next to them seems to be staring into space. The only other man in the photo is holding a cigarette and looking down toward the women who are laughing. He may be laughing too. All the others in the photo seem to be engaged in happy conversations. Everybody seems to be enjoying a good time on a fine, late summer day. Everybody, that is, except the old man staring expressionless into the emptiness as the moment becomes a monument in the camera’s dark chamber.

(Special thanks to Patricia Morrow and Eric “Thompson” Goettsche for their help on this one.)

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on September 21, 2018