Remembering Charles Dornbusch

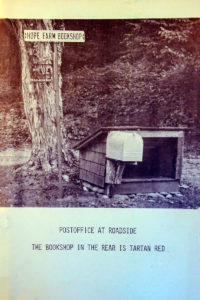

You can still see it there along the side of a seldom-traveled road in the hamlet of Cornwallville, a haunted house of sorts, or rather a low shed “with a history,” green-shingled and isolate, collapsing in upon itself. From this secluded spot, the proprietor of Hope Farm Bookshop used to dispatch and receive mail—a sizable volume of correspondence, book orders, invoices, manuscripts, and of course books, lots and lots of books. But that was long ago. A photo of this now-forgotten landmark graces the cover of a catalog issued by the bookshop in January 1975. The caption reads: “Postoffice at Roadside.” Visible just to the left is a street sign—reminiscent of those seen on suburban corners in the 1960s—emblazoned with the shop’s name. These days the sign is corroded and hardly legible, yet it endures as an accidental monument to a man who whose significance to this region rivals that of the mountains themselves. The crumbling “postoffice” and tarnished sign make for a melancholy scene, to be sure, yet for many a bibliophile and local history aficionado it will bring back fond memories.

For nearly three decades, Charles E. Dornbusch (1907-1990) operated his bookselling and publishing enterprise from this unlikely location. Or perhaps not so unlikely, given his mission to provide “professional bookservice for the Catskill Mountain area.” Having retired in 1962 after thirty-five years of service at the main branch of the New York Public Library, Charlie Dornbusch relocated to “the old Hope place,” a 19th century farmhouse that his mother and step-father had purchased in 1942. Her maiden name was Minor and she had deep roots in the Cornwallville area. Her son, having already made a name for himself as compiler of the 3-volume Military Bibliography of the Civil War, now embarked on a new career as genealogist, local historian, book publisher, and purveyor of what he liked to call “Catskilliana.” He set up his business in an outbuilding behind the farmhouse, which he had painted “tartan red,” perhaps to make it easier for customers astray to find the place. During the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, if there was anything you needed to know about the Catskill Mountains and the region around, Charlie Dornbusch was your man. If he was already acquainted with you and your interests, more often than not he would simply send his unsolicited recommendations your way, knowing what you needed before you did.

Which leads to another remarkable aspect of this most remarkable man: He was a genuine character. Nearly thirty years after his death, all you have to do is mention his name in certain quarters and the stories that follow will be sufficient to fill volumes. Mike Ryan, for instance, who knew Charlie well, recalls: “he had a woman’s head scarf (left at his shop by a customer) that he would wear when driving his red Chevy Nova around town and to the post office . . . merely to rile the locals . . . the ends of the red and black scotch plaid scarf would flutter out the window . . . the people who saw him doing double takes and him squealing with delight over it . . . a rare show of emotion. . . it reminded me of Toad in The Wind in the Willows.” Another who knew Charlie well is Jim Planck, who recounts this vivid moment at Charlie’s funeral: “I remember that when I first arrived at the cemetery, folks in attendance had not yet moved over to the gravesite, and as we started over I saw that there was a Bluebird sitting atop a stone right next to where his grave was to be. I took that as a special sign of his being blessed.”

I myself began a correspondence with “Mr. Dornbusch” in the early 1970s. I was just a kid. But when he detected my passion for all things Catskill Mountains, he immediately assumed the role of mentor. The books I bought from him back then are among my most cherished possessions today. One time—I must have been eighteen or nineteen—I stopped by the store to visit. We chatted for a while and he suggested I get in touch with this person he knew who could help me with whatever Catskills-related subject it was I was investigating. I asked to borrow a pencil and paper to write down the information. He gave me a stern look and said: “No pencil and notebook! What kind of writer are you?” Nobody had ever called me a writer before. I liked the sound of it. Ever since I have carried a pencil and notebook with me anyplace I go.

I could go on and on with stories about Charles Dornbusch, as I’m sure many of you reading this could too. I fell out of touch with him in the mid-eighties when I moved to the West Coast for some years. He died in 1990 as the result of an accident at home. In this age of the internet, I feel his absence more keenly with each passing year. It’s not easy to find places like Hope Farm Bookshop anymore. Perhaps it never was.

As for the bookshop’s proprietor, he of course is irreplaceable. But consider one last story. During its years of operation, Hope Farm Bookshop was open daily—except Mondays—from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Given that the store was located in what many would say is the middle of nowhere, Charlie did not get a lot of foot traffic. Whole days might go by without anybody showing up. Whenever he felt like taking a break, he’d tack a small index card to the door of the bookshop. One of these notices read: “Have gone to Point Lookout and will return promptly. Do wait.” Another said: “Have gone to East Durham for the necessities of living and will return shortly.” But my favorite had a little map sketched on it, along with these words: “Mr. Dornbusch has gone a strolling down the road. Do fetch him for your company will be enjoyed.” Of that there can be little doubt.

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the February 9, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)