Our Banner in the Woods

It hangs conspicuously in an inconspicuous spot. Measuring twelve by eighteen feet, the flag is suspended between a pair of trees at the edge of the woods where Maplecrest Road meets County Route 23C in East Jewett. No passing traveler can miss it. At night, the stars and stripes are illuminated with powerful beams, giving it an even more commanding appearance. Still, the ferocious mountain weather in these parts takes its toll, necessitating that the flag be replaced every couple years. The original version—retrieved from an old barn and bearing 48 stars—was raised by Tom and Lonna Hitchcock on September 16, 2001. They stopped to put it up on their way to a memorial service for Jeremy Glick, who was aboard the ill-fated United Flight 93, five days earlier. He and some of his fellow passengers banded together and foiled the hijackers before they could crash the jetliner into the United States Capitol. Instead, the plane came down in a remote field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. All 44 people on board, including the hijackers, perished. The flag set up by the Hitchcocks seventeen years ago—and now maintained by them and a small group of neighbors—was intended as a memorial but quickly became a local landmark. Today it ranks among the more significant works of installation art in the region.

As happens with any highly visible expression, the flag in East Jewett has attracted passionate devotees and equally passionate detractors. Anecdotal evidence suggests the former far and away outnumber the latter. Visitors to the area—charmed by the grand exhibit of color at the edge of what seems to them a howling wilderness—stop their cars in the middle of the road to take pictures. A local resident told me that he sometimes parks near the flag just so he can sit quietly and look at it. “It’s very calming and makes me feel like I’m in church.” For a large number of people, the flag serves as a stimulus for happy memories of parades, ballgames, summer vacations, and picnics. And it is worth noting that, for many motorists, this wayside display has come to serve as a navigation beacon, especially on dark and stormy nights. Even though it has many fans, the flag in East Jewett does upset some people. The erstwhile Windham Journal once printed a scathing letter from a member of the community railing against the size of the flag and hurling an apparent indignity at Tom Hitchcock by calling him “the town patriot.” The flag itself has been the target of vandals. Lights around it have been torn down, flowers have been ripped out of arrangements, and attempts have been made to pull the entire installation to the ground. Bewildering as all this may seem, impassioned response to a flag is nothing new.

In the spring of 1861, at the very start of the Civil War, the artist Frederic Church painted a small picture that today bears the title Our Banner in the Sky. In a short article published on May 19th of that year, a writer for the New-York Daily Tribune describes Church’s new picture as “a symbolical landscape embodying the stars and stripes.” Depicted on the canvas is “an evening scene, with long lines of red and gold typifying the stripes and a patch of blue sky with the dimly twinkling stars in a corner for the Union.” A blasted tree figures for a flagpole. Soaring above it is a large, dark bird—perhaps an eagle. The political allegory is unmistakable—and it irks the critic from the Tribune. He scolds Church for fooling with Mother Nature. “Such attempts are always artistic mistakes, for landscape effects are necessarily sensational and never moral.” In those days, “fidelity to nature” was a commonplace critical perspective in the New York artworld. That all began to change on April 12th, when Confederate artillery fired on Fort Sumter. By the next day, Union forces were short on ammunition and supplies. Adding to their difficulties: sections of the fort were ablaze. Surrender was inevitable. Major Robert Anderson, commander of the Union Forces, ordered a flag of truce raised—along with the American flag. Alas, the bombardment did not cease. Eventually, a Confederate officer approached and told Anderson the shelling would continue “so long as you keep the United States flag.” Begrudgingly, Anderson accepted the humiliating conditions of surrender. As a parting shot, however, the defeated Union soldiers started singing “Yankee Doodle” as they were being led out by their captors. As they passed the stars and stripes—now lying tattered and soiled on the ground—they saluted it. At that very moment, according to reports, a pile of cartridges exploded, killing two Union soldiers and injuring four others.

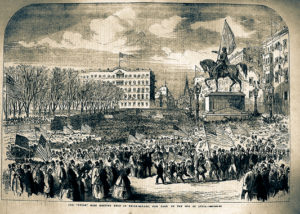

The rebels were ecstatic. The governor of South Carolina effused that this was “the first time in the history of this country that the stars and stripes have been humbled!” None of this played well in Northern papers and pulpits. The story of the flag’s ill treatment by Confederates unleased a furious Northern enthusiasm for the stars and stripes. In short order, a plethora of patriotic poems and sermons were published in the newspapers, venerating the flag as if it were a holy relic. On April 20th, a “great mass meeting of the people of New York in favor of sustaining the government” was held in Union Square. The space was jammed with people waving the red, white, and blue. The Evening Post reported that “from a tree near the stand fronting Broadway was the stained and tattered flag brought by Major Anderson from Fort Sumter.” On May 6th, a writer in the New York Times commented: “If anyone goes around among our soldiers now, and asks many the reason of their enlistment, they will probably say, ‘it was the insult to the old flag at Sumter,’ or ‘it is for the stars and stripes.’ Many unreflecting people laugh at this as an ignorant enthusiasm. But it is not. Who that knows human history or human nature, can doubt in regards to the power of an emblem. That simple emblem is a reality—it contains a history and a promise in itself.” And what is an emblem but something—an image, say, or a design, or a work of art—that suggests a truth or a fact not yet fully grasped. And without a firm grasp on the whispery whatnot that an emblem indicates, competing interpretations are bound to arise among the parties involved. And that’s when things can become . . . interesting.

The rebels were ecstatic. The governor of South Carolina effused that this was “the first time in the history of this country that the stars and stripes have been humbled!” None of this played well in Northern papers and pulpits. The story of the flag’s ill treatment by Confederates unleased a furious Northern enthusiasm for the stars and stripes. In short order, a plethora of patriotic poems and sermons were published in the newspapers, venerating the flag as if it were a holy relic. On April 20th, a “great mass meeting of the people of New York in favor of sustaining the government” was held in Union Square. The space was jammed with people waving the red, white, and blue. The Evening Post reported that “from a tree near the stand fronting Broadway was the stained and tattered flag brought by Major Anderson from Fort Sumter.” On May 6th, a writer in the New York Times commented: “If anyone goes around among our soldiers now, and asks many the reason of their enlistment, they will probably say, ‘it was the insult to the old flag at Sumter,’ or ‘it is for the stars and stripes.’ Many unreflecting people laugh at this as an ignorant enthusiasm. But it is not. Who that knows human history or human nature, can doubt in regards to the power of an emblem. That simple emblem is a reality—it contains a history and a promise in itself.” And what is an emblem but something—an image, say, or a design, or a work of art—that suggests a truth or a fact not yet fully grasped. And without a firm grasp on the whispery whatnot that an emblem indicates, competing interpretations are bound to arise among the parties involved. And that’s when things can become . . . interesting.

Almost a century later, the artist Jasper Johns—born in Georgia and raised in South Carolina—had a dream about the American flag. It came to him shortly after he took up residence in New York City following the Korean War. He had just finished a two year stint in the military. That dream led to the creation of his most famous work—simply titled Flag. And that’s what it is: an encaustic painting of an American flag, with little scraps of newspaper—not immediately discernible—embedded in the waxy surface. When Flag made its debut in 1955—the latter days of the McCarthy era—tempers flared. Many interpreted the painting as an assault upon truth, justice, and the American way. Some declared Flag an outright blasphemy. Johns himself always insisted that his painting had no political intentions. “I’m merely concerned with looking and seeing.” Over the course of time, the general response to Flag has mellowed. These days, casual viewers of the painting for the most part take it as a straightforward expression of patriotism. Posters of Flag can seen hanging on the walls of college dormitories and in the armories of the National Guard. “I wasn’t trying to make a patriotic statement,” Johns said in an interview. “Many people thought it was subversive and nasty. It’s funny how feeling has flipped.”

The musician John Cage—a close friend of Jasper Johns—once posed an impish question regarding interpretation: “How does the flag sit with us, we who don’t give a hoot for Betsy Ross, who never think of tea as a cause for parties?” To be sure, the big flag in East Jewett has been cause for a wide array of feeling among those who view it. Perhaps, as they say, nobody can look at an iconic image such as the American flag with an innocent eye. Some see old glory, some see bugbear. A few, though, close their eyes and just listen. They listen without thinking, without feeling. They listen for a certain fluttering, that ebb and flow of a balsam breeze against the dainty fabric that is our banner in the woods.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on November 30, 2018