On Shaker Mountain

They are long gone, the Shakers of Hancock, those people who established for themselves a sacred space on the mountain above their village. Here was where they conducted their outdoor worship. Here is where they received wonderful revelations and manifested many eccentricities. Here is where, over the course of a decade or so, the boundary between the visible and invisible gave way. Today that holy place on the western edge of Massachusetts is all but forgotten. Like an abandoned New England graveyard, it lies in the green neglect of an enclosing forest. Casual visitors to the site today are unaware of the remarkable Fourth of July celebration took place here in 1842.

They are long gone, the Shakers of Hancock, those people who established for themselves a sacred space on the mountain above their village. Here was where they conducted their outdoor worship. Here is where they received wonderful revelations and manifested many eccentricities. Here is where, over the course of a decade or so, the boundary between the visible and invisible gave way. Today that holy place on the western edge of Massachusetts is all but forgotten. Like an abandoned New England graveyard, it lies in the green neglect of an enclosing forest. Casual visitors to the site today are unaware of the remarkable Fourth of July celebration took place here in 1842.

In my travels around the Berkshires, I heard a few stories about that bygone day on Shaker Mountain, so I decided to look into it for myself. Those who are curious about such things can visit Shaker historic sites and museums, read the histories, and dig around in the archives. That’s what I did. Plus, there’s no shortage of Shaker material relics. Collecting them—especially the furniture—has long been a popular and often lucrative pastime. But what of the spiritual life of these people who set themselves apart from the world of getting and spending, who built their communities in full expectation that their God would actually come and dwell among them?

To gain some insight, I took a walk late one early June day, up the well-graded trail to the top of Shaker Mountain. The hike took less than an hour. Nobody else was on the trail. Clouds were lowering and rumbles of thunder echoed through the surrounding valleys. My only company was the faraway muffled roar of vehicles on Route 20. As I made the ascent, I mulled over what I had learned about the place the Shakers called their “Feast Ground.”

* * *

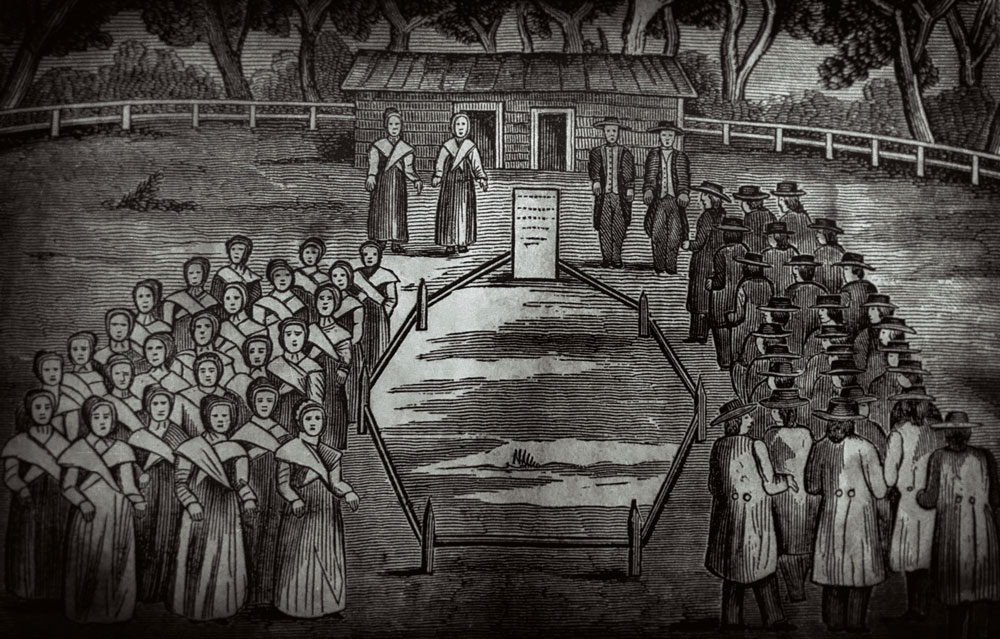

Independence Day in 1842 fell on a Monday. Early that morning the inhabitants of the Shaker community at Hancock, “both old and young,” according to a first-hand account, arose from their slumbers and donned their Sunday best. On top of their drab finery, each of the faithful put on “a most splendid Spiritual dress,” a costume visible only to those who could see “Spiritual things.” Few among the Shakers possessed this gift, and those who did were known as “instruments.” The rest of the community relied upon the instruments to keep them apprised of what was happening in the invisible world. When they finished dressing, they headed outside and joined in procession, setting forth toward the summit of a nearby peak dubbed “Mount Sinai.”

slumbers and donned their Sunday best. On top of their drab finery, each of the faithful put on “a most splendid Spiritual dress,” a costume visible only to those who could see “Spiritual things.” Few among the Shakers possessed this gift, and those who did were known as “instruments.” The rest of the community relied upon the instruments to keep them apprised of what was happening in the invisible world. When they finished dressing, they headed outside and joined in procession, setting forth toward the summit of a nearby peak dubbed “Mount Sinai.”

A mile and a half of rough walking along a vague path brought them to their destination: the “Feast Ground,” a small lot hewn from the thick forest of chestnut, oak, and elm. A makeshift wooden fence marked the bounds of the site. At the center of the enclosure was a low heap of rocks designated the “Fountain.” (Within a year, the rocks would be replaced by an impressive four-foot marble stone.) As one observer described the landmark, it was not a fountain of “literal waters, but of the water of life . . . exceedingly productive of spiritual gifts.” Alas, only the instruments could perceive the metaphysical glories of the Fountain, but everybody present could hear, with their own ears, the ethereal, downward-spiraling song of a lone veery in the dark woods beyond the enclosure.

The Feast Ground itself was only newly “revealed.” Just two weeks prior, a group of instruments—five men, all leading figures in the Shaker community— had been dispatched under divine injunction to locate the sacred space. The group was led by a senior instrument, one Joseph Wicker, who took direction from a “Holy Angel,” whom he alone could see. The instruments were also accompanied by a host of prominent spiritual personages, including the “Holy Savior” as well as Huldah the Hebrew Prophetess, John Calvin the Protestant Reformer, and a nameless “special messenger” sent by the founding leader of the Shakers, Mother Ann Lee. If nothing else, it was an impressive hiking party and they went straight up the steep side of the mountain.

The instruments knew they had arrived at the promised Feast Ground when one of them, a man named Joseph Patten, “was taken under violent operations and rolled from side to side among the trees but without the least injury.” Patten then got back on his feet and helped his companions establish the bounds of the Feast Ground, about a third of an acre in extent. Soon enough, Patten was again “under operations,” now channeling the spirit of “Father Calvin.” The voice, as if rising from the depths of an abandoned mine, proclaimed: “This spot was never drenched in blood, therefore it is holy consecrated ground, and the holy Angels will bring tidings from hill to hill.” The men concluded their work by piling rocks so that non-instruments would know where the Fountain stood. Lastly, they kneeled around the spiritual waters, “drinking and bathing” together, before returning home to share the news of their spiritual adventure.

The instruments knew they had arrived at the promised Feast Ground when one of them, a man named Joseph Patten, “was taken under violent operations and rolled from side to side among the trees but without the least injury.” Patten then got back on his feet and helped his companions establish the bounds of the Feast Ground, about a third of an acre in extent. Soon enough, Patten was again “under operations,” now channeling the spirit of “Father Calvin.” The voice, as if rising from the depths of an abandoned mine, proclaimed: “This spot was never drenched in blood, therefore it is holy consecrated ground, and the holy Angels will bring tidings from hill to hill.” The men concluded their work by piling rocks so that non-instruments would know where the Fountain stood. Lastly, they kneeled around the spiritual waters, “drinking and bathing” together, before returning home to share the news of their spiritual adventure.

Word spread quickly. The entire village was elated with the idea of “going for a meeting on the mountain” and joining in “a feast of fat things.” Over the next two weeks, additional work parties prepared the Feast Ground for the first “Mountain Meeting” on Sinai. The event was scheduled, not coincidentally, for the Fourth of July.

That glorious day had finally arrived. With most of the Shaker flock from Hancock now gathered in solemn rows around the Fountain, the festivities commenced. It went like this.

The Holy Savior got the show underway by speaking through the instrument Joseph Wicker: “I have come here this morning with a blessing for every one who has come to this place.” Another instrument, Martha Van Valen, exclaimed to the crowd: “There are one thousand spirits here, and they will unite in the praise of God with you! They will also drink at the fountain of living waters with you.” John the Revelator now arrived on the scene, offering a few pious sentiments through instrument Judith Collins. The next instrument gave voice to the Prophet Daniel: “Dear Brethren and Sisters, ye are not captives, ye are not in the lion’s den, ye are free children of Zion, ye can bow before your God unmolested.” The Holy Savior then returned, putting words in Joseph Wicker’s mouth: “Beloved children, if ye will draw near to the sparkling fountain, and do bathe in and drink of the livings waters, ye shall in truth partake of the waters of life and find refreshment to your weary souls.” Elder Nathaniel Deming turned and in his own voice addressed the congregation: “Jesus saith my sheep know my voice and a stranger they will not follow. My sheep hear my voice and they will follow me.” Then Elder Nathaniel called out: “Canaan! Canaan!” and the Shaker flock dropped to their hands and knees and began baa-ing like sheep and splashing uproariously in spiritual waters that few or none could see.

As this was going on, various instruments took turns delivering homilies from the spirit world. At one point Martha Van Valen called on instrument David Osborn to identify some of the many spirits in attendance at that Fourth of July Mountain Meeting. Osborn called out the names of famous leaders and generals from history, including Queen Isabella, Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Marquis de Lafayette—all to the oohs & aahs of the Shaker disciples who were done with their baa-ing.

No name was met with greater applause than that of George Washington. This may account for why he alone among the illustrious phantoms took the time to address the crowd. Martha Van Valen announced: “Brother George Washington said this is the most beautiful sound I ever heard on the 4th of July in all my life.” Elder Nathaniel stepped in to give direct voice to the general: “The whole world rings this day with the name of great George Washington, and it is a stink in my nostrils. For what did I endure the toils and fatigues that I did? Was it for worldly riches and honor? Nay, verily it was for the love of my country. For what did I deal out my food to the hungry and my clothing to the naked? Was it for pomp and grandeur, to gain a great name? Nay, verily, it was to free my country from tyranny and slavery.”

At the conclusion of George Washington’s oration, the Holy Savior stepped forth once more through the instrument Joseph Wicker. He conferred final blessings upon the congregation. They were instructed to collect freshly-fallen “manna” from the Feast Ground before wrapping up the meeting and returning to the village. They were back there by noon.

After that, the Shakers at Hancock conducted two Mountain Meetings per year for the next ten years, as did the 18 other Shaker communities on their own Feast Grounds throughout New England, New York, and the Midwest. This episode in Shaker history became known as the “Era of Manifestations” or “Mother Ann’s Work.” Eventually, unfavorable publicity, an influx of worldly curiosity-seekers, and repeated desecration of Feast Grounds by hostile neighbors prompted the Shaker Elders to end their Mountain Meetings. The Fountain Stones were removed and the Feast Grounds abandoned. Forest soon reclaimed the sites, and memories of the extraordinary things that took place on them faded away.

* * *

It was getting dark when I arrived at the Feast Ground. The air was close and vaguely redolent of ferns and flowers. If any of the spirits who attended the Shakers at their Mountain Meetings were present now, they weren’t revealing themselves to me. They know a worldly curiosity-seeker when they see one. The four corners of the sacred lot were marked with diminutive fencing, but otherwise no delineation. The ground within the enclosure was thick with bracken and low copses of chestnut, beech, and maple. I paused at the edge of the Feast Ground, where the Shaker faithful would make seven low bows before setting foot upon it. I took a picture and walked in.

I strolled about the vegetation—mindful of ticks—and tried to imagine the scene that unfolded here on that long-ago Fourth of July morning. No spirits, no waters of life, no luck. My head, as usual, was too filled with clamoring thoughts to see what can’t be seen. Call it an occlusion of imagination. “Wisdom evades the clever,” a venerable teacher once said. Or as my wise mother always told me: “You’re too clever for your own good.”

Oh well, the hour was growing late. Benightment was imminent. Time to go. I have nothing further to report about my visit to the Feast Ground on Mount Sinai, today known as Shaker Mountain. Except that, as I began my descent, a lone veery began to sing from the depths of the darkling forest.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in Berkshire Magazine, August 2021