On Paths

A path or trail is an expression of relationship, an accord between those who use it—and thereby maintain it—and the region it traverses. Paths made by deer and fox express something different from those made by human beings, though often such paths are shared. Over the course of time, paths come and go. Depending on circumstances, some of them evolve into roads and highways, while others disappear entirely. Many paths simply fall into obscurity, their maintenance dependent upon the tread of the infrequent passerby. The mountains and creeks of the Catskills are interlaced with myriad paths of all kinds, some leading to peculiar destinations. Most of these do not appear on any map.

Along the main drag in Jefferson Heights is an historical marker, a blue and yellow metal sign placed there by the New York Department of Education in 1932. On it, an arrow points vaguely toward the northeast, in the direction of the rural cemetery. The word “Footpath” appears in large font near the top of the sign. Below, in smaller font, are words indicating that here was once an Indian thoroughfare. It has long since fallen out of use. No visible trace remains. Not that there ever was much to see, even when the path had high traffic. According to Archer B. Hulbert—that venerable historian of footpaths and highways—the “bed of an Indian trail was very narrow, since made by only one traveler passing at a time.” These paths were not “designed” or “engineered” in the way today’s trails are. The Indian paths were kept open simply by the movement of pedestrians. If a path became “impenetrable because of the wind-strewn wreck of the forest, or by the action of the floods,” the Indian “merely sought out another pathway and broke it open by continual use.” Their extensive network of trails was informal and contingent, constantly changing as the situation on the ground required.

toward the northeast, in the direction of the rural cemetery. The word “Footpath” appears in large font near the top of the sign. Below, in smaller font, are words indicating that here was once an Indian thoroughfare. It has long since fallen out of use. No visible trace remains. Not that there ever was much to see, even when the path had high traffic. According to Archer B. Hulbert—that venerable historian of footpaths and highways—the “bed of an Indian trail was very narrow, since made by only one traveler passing at a time.” These paths were not “designed” or “engineered” in the way today’s trails are. The Indian paths were kept open simply by the movement of pedestrians. If a path became “impenetrable because of the wind-strewn wreck of the forest, or by the action of the floods,” the Indian “merely sought out another pathway and broke it open by continual use.” Their extensive network of trails was informal and contingent, constantly changing as the situation on the ground required.

In addition, the Eastern Woodland Indians did not mark their paths. It would seem they had no need to. Thomas Pownall—governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay prior to the Revolution—observed that when it came to navigating the forest, the Indian saw the way instantly, “and has, from Habit, this Impression continually on his Mind’s Eye, and will mark his courses as he runs, more readily than most Travellers who steer by the Compass. The Ranges of the Mountains, the Courses of the Rivers, the Bearings of the Peaks, the Knobs and Gaps in the Mountains, are all Land Marks, and Picture the Face of the Country on his Mind.” Archer Hulbert states it more directly: “The ‘blaze’ was a white man’s invention.”

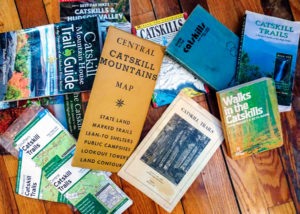

These mountains the Indians once called Onteora—“Land in the Sky”—are today entwined with hundreds of miles of state-authorized trails, well-maintained and colorfully blazed. “Junction points are marked with signboards,” says the Conservation Department’s 1969 booklet titled Catskill Trails, “and the routes themselves with special circular trail markers, so that is it practically impossible for even the merest novice in woodcraft to become lost.” In the years since those words were published, it has become even harder to get lost. A plethora of satellite-modulated guidebooks and handheld electronic devices aglow with high-resolution plats now guarantee there is no going astray in these mountains, no celebrated vista to be missed, no mournful plane wreck to be left undisturbed. All of this is in stark contrast to the ways of the former inhabitants, on whose unblazed paths, we are told by their historian, “Surprises were easily achieved.”

These mountains the Indians once called Onteora—“Land in the Sky”—are today entwined with hundreds of miles of state-authorized trails, well-maintained and colorfully blazed. “Junction points are marked with signboards,” says the Conservation Department’s 1969 booklet titled Catskill Trails, “and the routes themselves with special circular trail markers, so that is it practically impossible for even the merest novice in woodcraft to become lost.” In the years since those words were published, it has become even harder to get lost. A plethora of satellite-modulated guidebooks and handheld electronic devices aglow with high-resolution plats now guarantee there is no going astray in these mountains, no celebrated vista to be missed, no mournful plane wreck to be left undisturbed. All of this is in stark contrast to the ways of the former inhabitants, on whose unblazed paths, we are told by their historian, “Surprises were easily achieved.”

This is not to say certain astonishments do not await today’s visitor to the wild recesses. Washington Irving’s tale of Rip Van Winkle is, after all, admonitory. In the Catskill Mountains, anything can happen if you turn, ever so slightly, to the right or to the left, and depart from the beaten path. One time a lone hiker was descending along a state trail from one of the highest peaks in the range. It was late on a late October afternoon. The sun was going down. Soon he would be benighted. While still at considerable elevation and miles from the trailhead, the hiker came upon a trail junction he did not remember passing on the way up. Thinking that the faint and unblazed path veering off from the state-sanctioned route might lead to a secret vista or healing spring or other treasured place, he headed off on it. Through the darkening forest he walked a considerable distance. Just as doubt was getting the better of him, he spotted a low-walled enclosure of flat rocks, in the middle of which stood a single, upright slab of bluestone. On the rock was a lichen-encrusted inscription, barely discernible in the dimming light. As best could be figured, the words were: “It Doesn’t Get Better Later.” With darkness nearly upon him now, the hiker spared no time to meditate on what this epitaph might mean or how such a monument should come to be built in this place or why no mention of it appears in any history or guidebook to the Catskill Mountains. He beat a hasty return to the state-marked trail and groped his way down through darkness to his car.

In truth, nobody can vouch for the authenticity this wayward-seeming episode. Its author appears to have made an ill-considered turn: from skepticism to credulity, from the standard route of history into the nearly trackless domain of imagination. Oh well. Let us seek a way through this darkling wood, and by continual use perhaps break open a new path, a new way. No telling what surprises might be achieved.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on March 23, 2018