On Catskill Creek

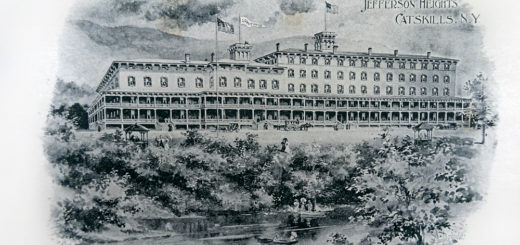

On certain days, Catskill Creek—when seen from Jefferson Heights above the village—seems to be flowing directly from the Delectable Mountains themselves. Or so it appeared to the artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848) when he first painted the scene in 1827, and so again in each of the subsequent pictures of the creek that he made—nine of them or more—over the next eighteen years. Catskill native James D. Pinckney (1807-1867) was similarly charmed by his hometown landscape. In his later years, he composed a series of reminiscences published in the Catskill Recorder and Democrat. “I know no lovelier spot,” he effuses in 1863. “In the Western distance, a single glance of the eye takes in the whole range of mountains, framing in a picture of hill anddell, and meadow and woodland; up the hill-side rises the hum of the busy Village which nestles at its foot; while away to the North-west stretches the valley of the Catskill, presenting a view which, we have the warrant of the poet-painter, Cole, in asserting, is unequalled by any scenery which had fallen under his vision in all his journeyings.” After reading Pinckney’s words—and looking once again at the current exhibition of Cole’s Catskill Creek paintings at Cedar Grove—I decided to conduct my own riparian investigation of the locale.

On certain days, Catskill Creek—when seen from Jefferson Heights above the village—seems to be flowing directly from the Delectable Mountains themselves. Or so it appeared to the artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848) when he first painted the scene in 1827, and so again in each of the subsequent pictures of the creek that he made—nine of them or more—over the next eighteen years. Catskill native James D. Pinckney (1807-1867) was similarly charmed by his hometown landscape. In his later years, he composed a series of reminiscences published in the Catskill Recorder and Democrat. “I know no lovelier spot,” he effuses in 1863. “In the Western distance, a single glance of the eye takes in the whole range of mountains, framing in a picture of hill anddell, and meadow and woodland; up the hill-side rises the hum of the busy Village which nestles at its foot; while away to the North-west stretches the valley of the Catskill, presenting a view which, we have the warrant of the poet-painter, Cole, in asserting, is unequalled by any scenery which had fallen under his vision in all his journeyings.” After reading Pinckney’s words—and looking once again at the current exhibition of Cole’s Catskill Creek paintings at Cedar Grove—I decided to conduct my own riparian investigation of the locale.

I own neither boat nor paddle, so I contacted a young archivist of my acquaintance who does—and he agreed to serve as my guide. Thus on a fine late afternoon in late July, I waited for him at the parking lot in front of the Catskill Middle School, which fronts the creek. Mine was the only vehicle in the lot—that is, until a police cruiser came along and parked just far enough away to keep an eye on me. A few minutes passed before my guide pulled up in a white pickup truck with a red canoe stowed in the back. The police cruiser left. We unloaded the canoe and hauled it down to the creek. On the opposite shore directly across from us was the county office building and its long swaths of parking lot.

Along this stretch, just before its confluence with the Hudson, Catskill Creek is tidal. Presently, the tide was out but about to turn. When we reached the put-in spot, all was calm. The water mirrored the cheery nebulosities of a summer sky, not to mention the redbrick quaintness of the village. The ambient air was redolent of mud—and something else. “All streams run into the sea,” it says in a good book, “yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the streams come, thither they return again.” As we prepared to commence our journey, my guide made a laconic observation, something about a recent raw sewage discharge in the vicinity. “Try not to get any water on you till we get past the first falls.” We launched the canoe without incident and started paddling upstream.

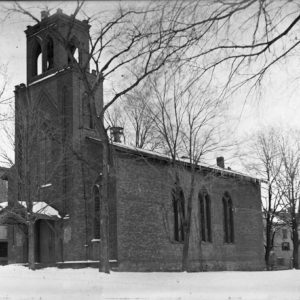

In no time, we passed the site of the former St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, close by the county office building. The original sanctuary, built along Church Street in 1804, burned down in 1839. The second iteration of St. Luke’s was designed by Thomas Cole himself and erected in 1840. According to one account from the time, the artist installed a trompe-l’oeil picture inside the church, “a beautiful window painted on the wall. It represented a brown stone arched window, with columns and capitals, and through the small glass panes a blue sky with clusters of magnificent cumulus clouds.” This distinctive structure served its congregation well for more than half a century. In 1899 the congregation opted to build a larger, stone edifice in a more desirable location—up the hill on William Street—and the Cole-designed church was sold off to one Amos Post. After that, the old church was repurposed into an automobile showroom and garage. The passage of time wrought more changes and the automobile business fell by the wayside. For a while, the old church housed the offices of a newspaper. Ultimately, though, the erstwhile house of worship fell into the same desuetude that claimed much of the village of Catskill throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. In 2002, the church designed by Thomas Cole was demolished to make room for an additional ten parking spaces deemed necessary for the new county office building. Thomas Cole seems to have anticipated the asphalt fate that befell his church. In May of 1838, he lamented in his journal: “But I am out of place; everything around, except delightful Nature herself, is conflicting with my feelings; there are few persons of real taste, & no opportunities for the artist of Genius to develop his powers; the utilitarian tide sets against the fine arts.” As our canoe skimmed past the parking lots, county office workers were leaving work for the day, getting into their sun-baked cars, and beating their respective paths home for the night.

On the opposite side of the creek, just south of where the schools and their parking lots are today, are lands once farmed by the Dubois family. In the first decades of the 19th century, there lived one James Dubois, who early in life moved to New York City to work as a clerk or an accountant or perhaps a scrivener. According to Pinckney, there was “no young man who ever left our town with more flattering prospects than James Dubois.” Yet something went awry for the young man. One day “news arrived that he had become suddenly deranged.” No satisfactory explanation for this lapse into madness was ever put forward, though to judge from the old newspapers it was not an uncommon affliction. Speculation around the village was that young Dubois had a sensitive temperament, and perhaps a rude remark by an uncouth employer was all it took to unsettle his mind. To conclude, then: “He was brought back to the old homestead, and, it is said that, for many years, he never spoke a word. Yet day after day, at a certain hour he would make the circuit of his father’s farm. In the pleasant Spring-time, in the burning Summer, in the mellow Autumn, and in the bitter-cold and snows of Winter, he would traverse that same route, making a round of miles, and return to his chamber, where he would remain in moody silence for the next twenty-four hours, then to resume his solitary walk over the well beaten track, which came to be known as ‘crazy Jim’s path.’ Many years subsequently, he suddenly resumed the exercise of speech, and, as though to compensate for his long silence, he became really garrulous. He abandoned his daily walk, and frequently visited the Village, but his reason never returned.”

We continued our upstream paddle past the newfangled brewery and under the recently refurbished Black Bridge, originally built for the Catskill Mountain Railway in 1882 and now serving as a pedestrian walkway over the creek. It was warm on the water that day, little in the way of a breeze.  Near the abutments for the soaring railroad bridge built in 1902 for the erstwhile West Shore Railroad, the first shallows appeared on the creek. Large, jagged, muck-encrusted rocks just below the surface made for tricky navigation. As we approached the concrete arch bridge for US 9W, we encountered the first “falls” on the creek. They weren’t much of a falls—more of an energetic fold in the surface of the warm water—but we did have to climb out of the canoe—taking health, if not our lives, in our own hands—and push it past the obstacle. We climbed back in and continued our leisurely paddle upstream, tracing the serpentine course of the now-rippling creek around a prominent point bar, gliding by a large outcrop of rock called the “Devil’s Aspect,” until arriving at the tumbling abutments of the second Catskill Mountain Railway bridge, which spanned the creek here from 1882 to 1918. This bridge replaced an earlier one built in 1835 for the ill-fated Catskill and Canajoharie Railroad. Peter Van Vechten Jr. was just a young boy when he observed the construction of this railroad across his family’s property at the end of Snake Road. Recalling those days in a 1908 letter published in the Catskill Examiner, he writes: “What a grand display when a succession of blasts were fired that hurled large rocks into the creek and over it; some large ones are still to be seen on the other side of the creek. At a safe distance, with many others, I have witnessed the air filled with debris of all sizes, reminding one of the scene at Mt. Sinai when Moses received the two tables of stone upon which were written the laws to govern the Jews, and which have since been the foundation of all laws that govern mankind. They also saw the greatest law breaker of the world, for he broke all the ten commandments with one stroke.” That day we did not spot any remnants of this original railroad bridge.

Near the abutments for the soaring railroad bridge built in 1902 for the erstwhile West Shore Railroad, the first shallows appeared on the creek. Large, jagged, muck-encrusted rocks just below the surface made for tricky navigation. As we approached the concrete arch bridge for US 9W, we encountered the first “falls” on the creek. They weren’t much of a falls—more of an energetic fold in the surface of the warm water—but we did have to climb out of the canoe—taking health, if not our lives, in our own hands—and push it past the obstacle. We climbed back in and continued our leisurely paddle upstream, tracing the serpentine course of the now-rippling creek around a prominent point bar, gliding by a large outcrop of rock called the “Devil’s Aspect,” until arriving at the tumbling abutments of the second Catskill Mountain Railway bridge, which spanned the creek here from 1882 to 1918. This bridge replaced an earlier one built in 1835 for the ill-fated Catskill and Canajoharie Railroad. Peter Van Vechten Jr. was just a young boy when he observed the construction of this railroad across his family’s property at the end of Snake Road. Recalling those days in a 1908 letter published in the Catskill Examiner, he writes: “What a grand display when a succession of blasts were fired that hurled large rocks into the creek and over it; some large ones are still to be seen on the other side of the creek. At a safe distance, with many others, I have witnessed the air filled with debris of all sizes, reminding one of the scene at Mt. Sinai when Moses received the two tables of stone upon which were written the laws to govern the Jews, and which have since been the foundation of all laws that govern mankind. They also saw the greatest law breaker of the world, for he broke all the ten commandments with one stroke.” That day we did not spot any remnants of this original railroad bridge.

At this point in our journey, we looked upstream spotted a more significant set of rapids. These would have required earnest effort to overcome, so we called it a day. We turned the canoe about and—aiming its bow in the direction of the brewery—retraced our course down Catskill Creek, returning unto the place from which we came, without further incident. And departed the scene in good health.

(Special thanks to Jonathan Palmer, Archivist & Deputy Greene County Historian, Vedder Research Library, Coxsackie NY.)

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 2, 2019