Of Men and Wolves

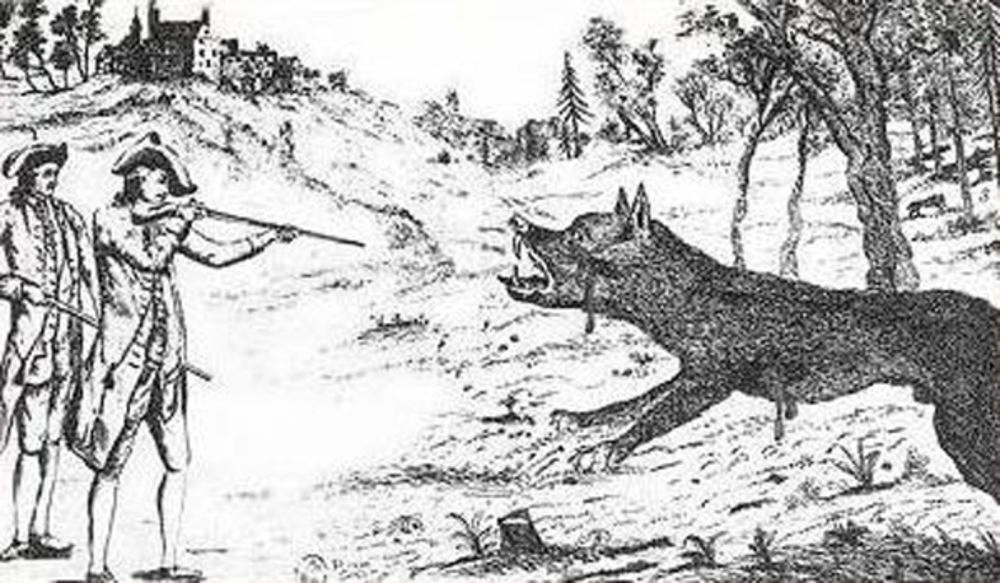

The year 1815 was a difficult one here on the Mountaintop, both for human beings and for wolves. At least that’s the sense one gets from reading Reverend Henry Prout’s Old Times in Windham. Back in those days, most of the territory around here was still thick with first growth forest. The Eastern Wolf—Canis lycaon—was plentiful, while pioneer farms were few and far between.

Prout reports that one night in May of that year, fifty-seven-year-old Elizur Wheeler heard a noise in the barnyard. He immediately dashed out to check on the livestock, only to come face to face with a sizable wolf. Without a moment’s hesitation, “Mr. Wheeler engaged the wolf in a hand to hand struggle until his daughter Lucy came with an axe and dispatched him.” Elizur Wheeler walked away from the encounter with a minor bite mark and a terrific story. This he shared “cheerfully” among his friends while showing off his wound. Not long after that, he began to display disturbing symptoms. Indeed, he seemed to be going mad. “In the course of no very long time,” reports the reverend, Elizur Wheeler was dead. The barely legible inscription on his stone in Ashland’s  Pleasant Valley Cemetery reads: “died of Hydrophobia.” The wolf that had bitten him was infected with rabies.

Pleasant Valley Cemetery reads: “died of Hydrophobia.” The wolf that had bitten him was infected with rabies.

Later that same year over in Big Hollow (now Maplecrest), Richard Peck—age sixty-two and veteran of the American Revolutionary War—heard a noise out in the barnyard. He called to his nineteen-year-old son, Peleg, to check it out. Peleg dashed into the yard and found a large wolf among the cows. “Bring me an axe!” the young man shouted to his father. Weapon then in hand, Peleg proceeded to “dispatch” the wolf. He suffered only a minor wound on his face. The immediate danger was past, but nine days later—while chatting with a neighbor, perhaps recounting his story of the wolf—Peleg began to suffer a strange sensation. He exclaimed: “I feel as though I could fight the whole world.” He swung around and “commenced kicking the barn violently.” The doctor was called but at that point nothing could be done. A few days later the young man died of rabies. According to Prout’s informant, as the remains were being transported over to Lexington Cemetery “the wolves set up a dismal howling on the mountain on the opposite side of the creek, and seemed to be moving in a parallel direction.”

The virus we now know as rabies is ancient in origin and has long been a scourge to human beings. The Greek physicians of Aristotle’s day called it hydrophobia—that is, “fear of water”—because a common symptom of it in humans is to be tormented simultaneously by fierce thirst and a terror of water. Mere mention of the word “water” is sufficient to induce violent spasms in  some victims. As the disease progresses, a person may experience delirium and wild hallucinations. Yet all mammals are susceptible to it, including wolves and domestic pets. Early on, it was recognized that transmission occurred through the bite of an infected animal. Once contracted, the disease almost always proves fatal.

some victims. As the disease progresses, a person may experience delirium and wild hallucinations. Yet all mammals are susceptible to it, including wolves and domestic pets. Early on, it was recognized that transmission occurred through the bite of an infected animal. Once contracted, the disease almost always proves fatal.

But things change. In the decades following the gruesome deaths of Elizur Wheeler and Peleg Peck, the forests across the region were cleared, settlements and pastures were established, and the wolf was systematically exterminated from the northeastern United States. The last one in New York State was shot and killed in the 1890s. Meanwhile over in France, Louis Pasteur and Émile Roux in 1885 developed a vaccination against rabies. Over the course of the next several decades this served to eliminate a mortal threat, at least for those of us living in the developed world. These days nobody on the Mountaintop worries about dying from hydrophobia.

In the end, so little stands between ourselves and oblivion. Beyond living memory there are only names and dates inscribed on erodible stones, brief reports in moldering newspapers, a paragraph or two in a forgotten book, or corrupting data upon a dissipating cloud. In Pleasant Valley Cemetery, for instance, fading tombstones, side by side, mark the graves of Elizur Wheeler and his daughter Lucy. Over the mountain in Lexington Cemetery, it’s the same story. Richard Peck, after his son’s death, lived another twenty-two years, arriving at the ripe old age of 87. His marker—along with those of his first and second wives—are still to be found among the other slanting and broken stones. Their graves, for the time being, are locatable. But what of Peleg Peck’s? No sign of him in that burying ground, though his remains are purportedly there. At one time, a monument may have marked his grave, but it’s now lost. Just like the wolf from these parts.

Nevertheless, something of those extirpated forest canines lives on—in the form of a hybridized species called “coyotes” or “coydogs.” And who knows, something too of Peleg Peck may endure, as when night falls and the coydogs set up their eerie serenading on the mountain, and the import of it—the ferocious emptiness—seems to follow in a direction parallel to the passage of time. Go out and listen for it. You won’t have long to wait.

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the February 2, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)