Names on the Mountains

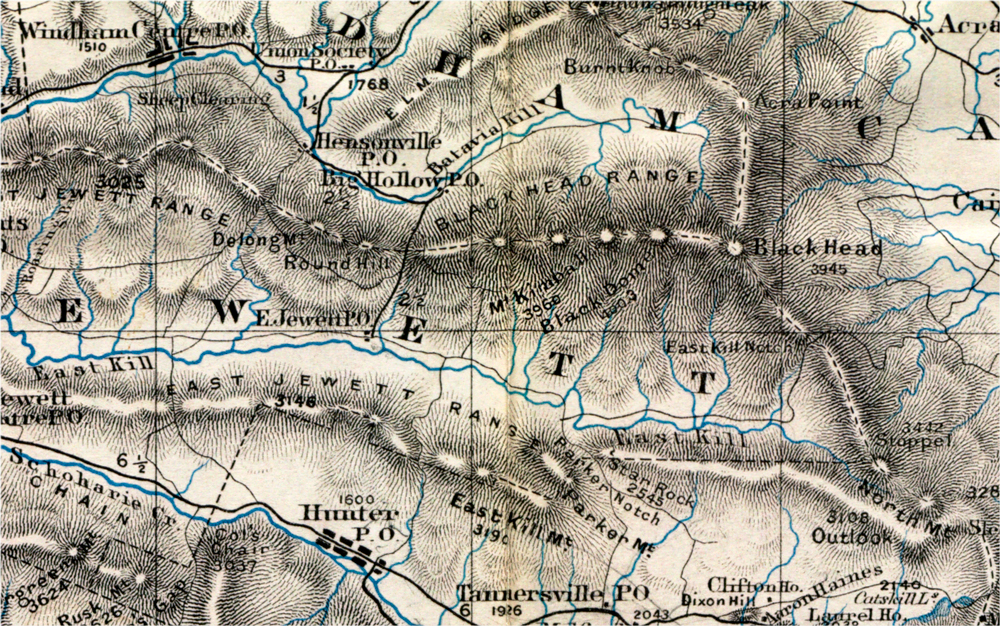

The map, they say, is not the territory, but a map does come in handy when trying to find your way around the territory. The region of the highest peaks in the Catskills—including all of the Mountaintop—had to wait much longer for a proper geographic reckoning than most places in the contiguous United States. The first scientifically accurate map of the area did not appear until 1879—and it was all due to the efforts of Arnold Henry Guyot, professor of Physical Geography and Geology at Princeton University.

From 1862 to 1879, Guyot spent his summers—day after day, week after week—bushwhacking his way to the summits of most of the mountains in the Catskills. He and a cadre of assistants hauled barometers, theodolites, and sextants up the steep slopes in order to gather the necessary data to make the map. Guyot liked to refer to these labors as his “vacation work.” His friend James Dwight Dana later recalled: “In several cases, his only chance for making his triangulation was by climbing to the tops of the highest trees, and then there was difficulty in identifying the distant, featureless, forest-buried summits.” Among Guyot’s more significant accomplishments was the discovery of the true highest peak in the Catskills. Up until that time, it was widely believed that Kaaterskill High Peak was the culminating point of the range, but Guyot proved that Slide Mountain down in Ulster County was, in fact, the highest. Not only that, but he determined that twenty other Catskill summits were also loftier than the now-diminished High Peak.

In addition to the arduous physical labor of getting to the tops of so many unfrequented mountains, Guyot was faced with challenges of nomenclature. “Most of the peaks measured,” he writes in 1880, “were, as usual in American wilderness, without names. I had to find some fitting appellations.” On top of that, some peaks possessed names that Guyot simply didn’t approve of: “Those in use, such as Roundtop and High Peak, North and South Mountains, are so often repeated in all parts of the Catskills that to prevent confusion it was sometimes necessary to change or to qualify them.” In this regard, the Princeton professor took more than a few liberties.

A comparison of the names used by Guyot on his 1879 map with those in common use today for the same peaks reveals a number of surprising differences. For example, the mountain now  known as Huntersfield is identified by Guyot as “Ashland Pinnacle,” and the mountain today called Ashland Pinnacle is left nameless. The modest prominence above Hensonville now called Round Hill is, according to Guyot, “DeLong Mountain.” Twin Mountain over in Platte Clove he calls “Schoharie Peaks.” And perhaps most significantly, the mountain known as Thomas Cole—fourth highest in all of the Catskills—was rechristened by Guyot as “Mount Kimball.” Now where did that name come from? Apparently it was a gesture on his part to honor a favorite field assistant: “Most of the aneroid observations,” he explains, “I owe to H. Kimball, the most indefatigable and skillful mountain climber of the Catskills.” It would seem that the license to name features on the landscape is a perk that comes with making one’s own maps, but this is no guarantee that any of those names will stick.

known as Huntersfield is identified by Guyot as “Ashland Pinnacle,” and the mountain today called Ashland Pinnacle is left nameless. The modest prominence above Hensonville now called Round Hill is, according to Guyot, “DeLong Mountain.” Twin Mountain over in Platte Clove he calls “Schoharie Peaks.” And perhaps most significantly, the mountain known as Thomas Cole—fourth highest in all of the Catskills—was rechristened by Guyot as “Mount Kimball.” Now where did that name come from? Apparently it was a gesture on his part to honor a favorite field assistant: “Most of the aneroid observations,” he explains, “I owe to H. Kimball, the most indefatigable and skillful mountain climber of the Catskills.” It would seem that the license to name features on the landscape is a perk that comes with making one’s own maps, but this is no guarantee that any of those names will stick.

All this cartographic comparison leads to the famous question posed by Shakespeare’s Juliet: “What’s in a name?” Over time, names on the land do change, but not overnight, nor in the course a single human lifetime. Who alive today calls the Hudson the “North River?” Hardly anyone, I would guess, but in Guyot’s day it was still commonplace to refer to the river by the name bestowed on it in 17th century: North River. Psychologists have long recognized that a new or different name for something alters the way we experience it, how we feel about it. Proverbial wisdom too recognizes the powerful influence of names. The ancient Romans had an expression, “a name is knowing”, which is perhaps more accurately translated as “a name is a spirit.” The old names—and the failed names, such as Mount Kimball or the Schoharie Peaks—suggest a kind of shadow-life on the landscape that, if attended to, can deepen our understanding of this place we now call the Mountaintop. It also reminds us that someday, maybe not in our lifetimes or those of our children or grandchildren, but someday, this place too will have another name—and along with it, a shadow-life deeper still.

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the January 12, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)