Kindred Spirits

The painting is called Kindred Spirits. It was created by Asher B. Durand in 1849 to memorialize his close friend and fellow landscape artist Thomas Cole, who died unexpectedly the previous year. The two men enjoyed their outings together in the untrammeled mountains of upstate New York. There they would climb and sketch and paint under the open sky. Durand referred to these creative excursions as “hard-work-play.” In later years, he penned a series of letters offering advice to young artists. He writes: “Let me earnestly recommend to you one studio which you may freely enter and receive in liberal measure the most sure and safe instruction ever meted to any pupil, provide you possess a common share of that truthful perception, which God gives to every true and faithful artist—the Studio of Nature.” When it comes to learning the ropes of landscape painting, a good hike beats any art school. Better yet, make it a hike with a chum, one who shares the love of hard-work-play, a kindred spirit.

Durand’s picture—by far his most famous—was commissioned by a wealthy businessman and patron of the arts named Jonathan Sturges. It was intended as a gift for the poet William Cullen Bryant, another good friend of Cole. Both poet and painter are depicted on Durand’s canvas, the two of them standing on a precipitous ledge in the midst of a wild gorge that seems an idealized version of Kaaterskill Clove. In the foreground are the shattered remains of a blasted tree, suggesting a barrier or threshold beyond which things start to get interesting. Look out! From the opposing cliff a bird of prey swoops down, while another—perhaps an eagle—soars conspicuously in the distance. Below the precipice are the swift waters of a mountain creek, clotted with giant boulders. Just upstream a moderate cascade plunges through a cleft in the bedrock. Further up the ravine is another falls, significantly more lofty. Beyond that, mountains rise upon blue mountains. Then the sky. Other than poet and painter—both well-dressed—and their names carved into a nearby tree—not to mention the signature “A.B. Durand 1849” carved into the base of the ledge upon which they stand—no sign of human presence is evident in this painting. You could say that Kindred Spirits is giving us a glimpse into the Studio of Nature itself, or the lambent headwaters of the Lethe.

Who knows but that, in their own fashion, the legalistic authors of Article XIV of the New York State Constitution had Kindred Spirits in mind when they wrote: “The lands of the state, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands.” Perhaps too the current governor was thinking of Durand’s painting when he touted his “Adventure New York” initiative in 2017, which provided 50 million dollars “to connect more New York families and visitors with the great outdoors.” More than a million of those dollars were “invested” in the Department of Environmental Conservation’s management unit known as the “Kaaterskill Falls Riparian Area.” A good chunk of that money went toward the installation of 500 feet of split rail fencing, which—according to a recent press release—“serves as both a physical and visual barrier to alert the public to the potential dangers of proceeding further.” Those dangers are indeed formidable, especially for those eager to make their own pictures out there along the ne plus ultra of one of the highest waterfalls in the northeast. According to a recent article in the NY Times, there have been eight fatal accidents at Kaaterskill Falls since 1992, the last four of which involved people “either taking or posing for pictures.” Entry into the Studio of Nature at times comes at a steep price.

or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands.” Perhaps too the current governor was thinking of Durand’s painting when he touted his “Adventure New York” initiative in 2017, which provided 50 million dollars “to connect more New York families and visitors with the great outdoors.” More than a million of those dollars were “invested” in the Department of Environmental Conservation’s management unit known as the “Kaaterskill Falls Riparian Area.” A good chunk of that money went toward the installation of 500 feet of split rail fencing, which—according to a recent press release—“serves as both a physical and visual barrier to alert the public to the potential dangers of proceeding further.” Those dangers are indeed formidable, especially for those eager to make their own pictures out there along the ne plus ultra of one of the highest waterfalls in the northeast. According to a recent article in the NY Times, there have been eight fatal accidents at Kaaterskill Falls since 1992, the last four of which involved people “either taking or posing for pictures.” Entry into the Studio of Nature at times comes at a steep price.

Durand painted Kindred Spirits to memorialize a friend, yet it also stands as a monument to friendship itself. At least it seems that way to me. And the older I get, the more so it seems. In 1979 I was a college student studying forestry in Maine. That summer I was hired by the Mohonk Preserve (in those days called the Mohonk Trust) to serve as a “wilderness ranger.” I lived in a drafty shack by myself, a mile or more from any human neighbor, on the shore of a diminutive body of water called Duck Pond. My duties included managing a small walk-in campground and conducting an ecological research project. A “gas shortage” that summer meant I pretty much had the place to myself. So I spent a lot of time reading books and hanging around with the “rock rangers” up at the Trapps. The rock rangers were a scruffy corps of supremely talented rock climbers—artists in their own right—who were employed by the Trust to sell passes and to patrol the cliffs of what is probably the most congested climbing area in North America. In those days, the rock rangers lived in their own shacks at a place called the Uberfall.

The rock ranger in charge was a jovial fellow in his late twenties by the name of Chuck Liff. Chuck had a big beard, a big laugh, and an even bigger heart. He was a kind of big brother to me that summer, and he taught me how to rock climb. No matter how despondent I sometimes became over events great or small that were looming in those times—whether it be the sorrows of a wobbly romance, the drifting plumes from Three Mile Island, or the prospect of Skylab crashing down from the heavens upon us—Chuck was an unfailing spring of good cheer. He always welcomed me and the other rangers into his camp. Many an evening we would sit around the fire at the base of those shadowy cliffs and devour big pans of his “Core Meltdown Cornbread.” Chuck would regale us with stories of the mountains, or tell long jokes, or read lively passages from the writings of Edward Abbey to stir our enthusiasm for being in the world. Those were good days. Looking back now, I can say they had a profoundly greater effect on the course of my life than the four years of forestry education I endured in Maine. I never saw Chuck again after that summer, but I thought of him often, and fondly.

A few years ago, thanks to the internet, I was able to track Chuck down. I discovered that after completing his graduate work in Systems Ecology, he went on to a career with the Environmental Protection Agency and then the US Forest Service. I found a Forest Service webpage that invited me to “Contact Chuck Liff.” The instructions said: “Please enter your contact information and comment below. Please note—if you incorrectly enter your email address, Chuck Liff will not be able to contact you.” I did not provide my contact information. Once again thanks to the internet, I already knew that Chuck had passed away, at age sixty, just a month prior. Pancreatic cancer.

Not long after that, I found myself in New Paltz for the first time in years. I stopped in at the venerable climbing store, Rock and Snow. Inside the front door of the shop was an alcove that housed a small museum of climbing gear from days gone by. Displayed in glass cases were old ropes, vintage hardware, timeworn climbing shoes, and moldering guidebooks to the “Gunks.” As I was looking over all that old gear now entombed behind museum glass, a grief that had been dogging me for more than a month—stemming from Chuck’s death, from missed opportunities, from the mere and savage passage of time—became more acute. I might as well have been standing in a funeral parlor.

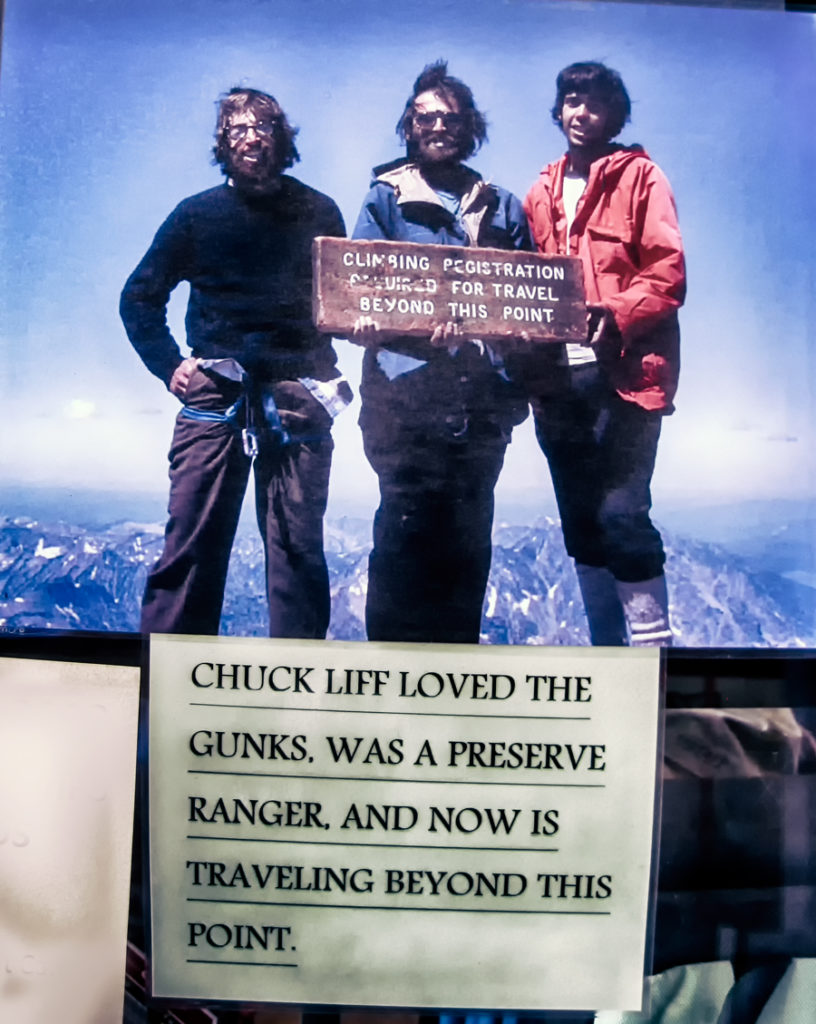

But then I turned from the glass sarcophagus and saw on the wall an 8×10 photo somebody had tacked up. It was a picture of Chuck—at the age I remember him being—along with a couple of his climbing buddies. They are standing, three kindred spirits, beaming atop a soaring peak somewhere in the American west, a great blue sky swooping down around them, range upon range of blue mountains cascading out into lambent distances. The three friends are holding a weather-beaten Park Service sign that reads: “Climbing Registration Required For Travel Beyond This Point.” They had hauled it with them up to the summit. No doubt the whole thing was a prank devised by Chuck himself. Below this glorious photo was a caption that read: “Chuck Liff Loved the Gunks, Was a Preserve Ranger, And Now Is Traveling Beyond This Point.” These days when I look into Durand’s painting—past the shattered tree, the roaring waterfalls, and the savage walls of the ravine—I can almost see Chuck standing there, on the summit of that last blue mountain, where it touches the sky.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 31, 2018