Kate Hill

The “Great Wall of Manitou”—otherwise known as the Catskill Escarpment—extends for more than twenty miles, roughly paralleling the course of the Hudson River. Nearly fifty years ago, historian Alf Evers noted that the “great wall is almost entirely without human habitation.” It remains so to this day. Where exactly this mountain wall commences and terminates remains a source of lively debate. I like to think it begins at Overlook Mountain above the town of Woodstock and ends at Kate Hill near the hamlet of East Windham. Along the escarpment just north of Palenville is the famed “Pine Orchard”—once upon a time the site of the Catskill Mountain House. Elsewhere along the great wall are three of the higher mountains in the Catskills: Kaaterskill High Peak, Blackhead Mountain, and Windham High Peak. State-sanctioned trails lead to the summits of all but two: Plattekill Mountain and Kate Hill. The former—at an elevation of 3,100 feet—is the 79th highest peak in the Catskills. Thus it attracts the attention of those whose mission it is to ascend the hundred highest summits in the range, and receive a trophy of sorts. At the more modest elevation of 2,392 feet and lacking an inspirational “Five State View,” Kate Hill is ignored by nearly everyone except the occasional hunter. Passing motorists along Route 23 take no notice of it. Many who live in its demure shadow don’t even know its name.

When James Fenimore Cooper’s character Natty Bumppo was asked what all was to be seen from the acclaimed ledge at the Pine Orchard, he replied: “Creation! All creation!” When John Burroughs climbed Slide Mountain—highest of all the Catskill Mountains—in 1885, he found the summit cleared of its trees: “The low, stunted growth of spruce and fir which clothes the top of Slide has been cut away over a small space on the highest point, laying open the view on nearly all sides. Here we sat down and enjoyed our triumph. We saw the world as the hawk or the balloonist sees it when he is three thousand feet in the air. How soft and flowing all the outlines of the hills and mountains beneath us looked!” A poet recently exclaimed of a lookout point on Kaaterskill High Peak: “From here one admires how the Hudson Valley throws itself together!” Such elevated grandeur. By comparison, Kate Hill would seem a nowhere: no breathtaking view, no great height, no glorious history or poetry attached to it. But in early June, the summit of this unassuming crest does present a lush, grassy woodland of hophornbeam, soft maple, and paper birch. Here and there is an overturned rock, the work of a hungry bear looking for grubs. Heaps of scat are abundant in the thick grass. Ovenbird, wood thrush, and red-eyed vireo fill the forest canopy with song as the muffled roar of motors drifts upslope from Route 23. The blue sky is filtered through chlorophyllic haze, the green is diaphanous and all-enclosing.

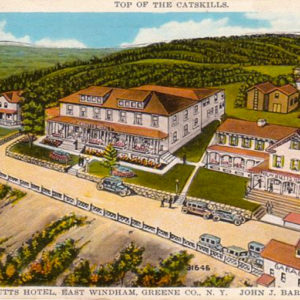

Although Kate Hill itself has never enjoyed the attention of poets, painters, or hikers, the hamlet of East Windham—which lies at its very foot—was for many years a popular tourist resort. The hamlet—or what remains of it—lies close to the notch along Route 23. Writing in 1884, the Durham town historian—J.G. Borthwick—noted that “the keeping of summer boarders is becoming a business of increasing importance in this town.” He neglects to mention another business of increasing importance: liquor. In those days of uncompromising temperance sentiment, East Windham was the only place around to get any booze. In his brief summary of the boardinghouses in East Windham, Borthwick gives a shout out to the Grand View Mountain House (which would burn down three years later), the Butts House, and the Summit House. Of the latter, he reports “it was built in 1848 by Barney Butts, who was the most famous hunter in this section of the mountains.

He possessed remarkable courage and powers of endurance, and it was his special delight to hunt bears, and his guests were often gratified not only in hearing him rehearse the many intensely interesting incidents of bear hunting, but they were permitted to form a personal acquaintance with bruin himself, tamed and subdued by Mr. Butts’ skill.” A couple years earlier, one of Mr. Butts’s “subdued” bears went AWOL, prompting its keeper to issue this notice in the local paper: “Lost from the Summit House, East Windham, a black bear belonging to Barney Butts. He had four legs and three feet, was in good condition though not particularly handsome. Five dollars reward will be paid to any person who will return him safe and sound, no questions asked—of the bear.”

Questions of other another sort could be asked—at least in later years—of the renowned Mrs. Taylor. Larry Tompkins—in his book Out Windham Way—recounts the June 1930 arrival in East Windham of the Taylors, “a well known family of gypsies, who have been coming to this section, off and on for twenty-seven years.” Mrs. Taylor was known as “one of the best fortune tellers in the state, but is no longer able to give Readings, much to the regret of all who have formerly experienced her unusual powers, owing to the present laws of the state which prohibit practice of the ancient art for money.” The future, at least according to the Laws of New York, is required to be free and open to all citizens.

The carefree summer days of boardinghouse vacations in East Windham continued on through the twentieth century, though the number of guests began to dwindle—as they did everywhere else in the region—following the Second World War. The death knell came in September, 1964, when a large fire—aided by high winds—consumed several buildings including two boardinghouses that were still in operation. In the words of Windham Town Historian Patricia Morrow: “All these places are gone now, either having been destroyed by fire or succumbed to the elements and years of neglect.”

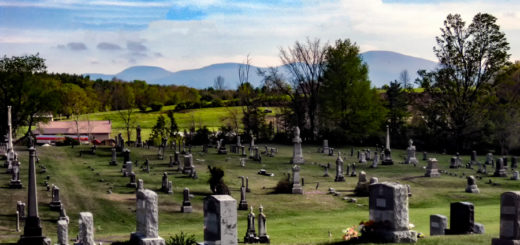

The glory days of the East Windham boardinghouses are long past. Trees have since grown in, covering the old hotel foundations. Traffic speeds by on Route 23, commuters and shoppers hurtling down the mountain toward new-fangled destinies. A large portion of Kate Hill has been acquired by the City of New York to protect its water supply. In coming decades, the shade on its slopes will only grow thicker. In its lush forsakenness, it has already become the haunt of free-roaming bears. Yet some things do not change. In the State of New York, fortune-telling remains a Class B misdemeanor.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on June 15, 2018