Kaaterskill Falls in Winter

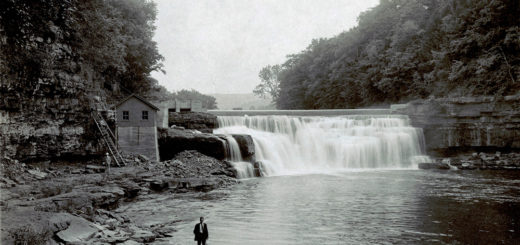

During the bitter winter of 1843, the artist Thomas Cole made an arduous day trip by sleigh from his home in the village of Catskill to the precipice of Kaaterskill Falls. He and his traveling companions were “in search of the wintry picturesque.” They certainly found it that day. A prolonged cold snap—much like the one the Mountaintop has experienced in recent weeks—had transformed the 170-foot upper cascade into “a gigantic tower of ice, reaching from the basin of the waterfall to the very summit of the crags.”

Hoping on this January day to enjoy a bit of the wintry picturesque myself, I head out by automobile—heat cranked up—from my home on Paradise Hill and arrive at Kaaterskill Falls twenty minutes later. As it turns out, this is the coldest day of the year thus far—several degrees below zero. I am the only one here.

In the 19th century, Kaaterskill Falls was one of the most popular tourist destinations in America. Descriptions of the site by literary travelers abound, but most of these encomiums were composed during the gentle days of summer, when ample accommodation and cooling refreshment were readily available at nearby hostelries. But once the cold weather set in, it was another story: winds began to howl, hotels and boarding houses were shuttered, snow piled up, and rare was the human visitor. Kaaterskill Falls became a forlorn and nearly inaccessible spot. No wonder so few descriptions of it in winter have come down to us from those times. Cole’s account is both realistic and precise—he even explains the physics of how the immense cone of ice forms around plummeting water: “the spray first congeals in a circle round the foot of the Fall, and as long as the frost continues, this circular wall keeps rising until it reaches the summit of the cataract.”

A more fanciful sketch of the Falls in winter is provided by Cole’s good friend William Cullen Bryant, the poet, who describes it as:

A palace of ice where his torrent falls,

With turret, and arch, and fretwork fair,

And pillars blue as the summer air.

In this poem titled “Catterskill Falls,” Bryant recounts a story—shared with him, he claims, by certain “gray-haired woodsmen”—of a young  hunter who finds his way in midwinter to the frozen cataract. Upon arriving at the base of the upper falls, he collapses into a cold-induced swoon, imagining “thin shadows” swimming “in the faint moonshine.” To his astonishment then, these unlikely forms take on the “ghastly likeness of men.” Much along the lines of Rip Van Winkle, the young man seems to have run into denizens of an otherworld. At the poem’s conclusion, he awakens to find himself tucked into a bearskin bed in a rustic cabin, under the care of hunters who had found him unconscious at the foot of the frozen Falls.

hunter who finds his way in midwinter to the frozen cataract. Upon arriving at the base of the upper falls, he collapses into a cold-induced swoon, imagining “thin shadows” swimming “in the faint moonshine.” To his astonishment then, these unlikely forms take on the “ghastly likeness of men.” Much along the lines of Rip Van Winkle, the young man seems to have run into denizens of an otherworld. At the poem’s conclusion, he awakens to find himself tucked into a bearskin bed in a rustic cabin, under the care of hunters who had found him unconscious at the foot of the frozen Falls.

Meanwhile back in the 21st century, I make my way from the trailhead parking lot down to the recently installed observation platform—seemingly a paddock with a view—designed to keep the public safe while they enjoy their recreational experience at Kaaterskill Falls. From here the view into the chasm below is much the same as Cole described long ago: there’s the immense cone of ice, the “festoons of glittering icicles”, the absence of moving water and gush of spray. “All is silent and motionless as death.” And it sure is cold—too cold to be standing around for very long enjoying a glimpse of the wintry picturesque. I stamp my cold feet and head down toward the lip of the Falls, which until not long ago was easily approachable. Nowadays the way is barred by a sturdy fence—yet another authorized enhancement to public safety. Secured to this barrier is a formidable piece of signage that reads: “DANGER! Numerous FATALITIES and serious injuries have occurred at Kaaterskill Falls. There is no safe way to reach the lower portion of the falls from here. Wet rocks are extremely slippery. It is unsafe to hike any further.” Icy rocks, presumably, are even more slippery. I have no intention of proceeding any further.

As I turn back from the precipice, I spot a man approaching along the snowy trail. We exchange the greetings normally expected of strangers who encounter each other in the subzero middle of nowhere. I ask what brings him out here on the coldest day of the year. He says he’s from the City and has come up for the weekend to go skiing, but it’s too cold for that. Nevertheless, he wants to spend a little time outdoors so he has come to Kaaterskill Falls, a place, he says, he learned about on Instagram.

I ask him what he does for a living. He’s a lawyer. He tells me his firm is currently representing a client who is suing a certain town in New England that has a waterfall “just like this one” because “people are always falling off it and there’s not a single sign warning them to stay away from the edge.” People, it seems, need to be warned of the potential perils—no matter how obvious—that await them in the great outdoors. I point to State of New York’s sign regarding the danger of Kaaterskill Falls. He nods solemnly and says: “Yeah, that’s right. You want to stay ahead of the pain.”

I couldn’t agree more. My hands and feet are numb. It’s time to head back to the car.

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the January 12, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)