Hotel Kaaterskill

Hotel Kaaterskill was a house built of spite. Legend has it that in the summer of 1880, George F. Harding—a highly successful Philadelphia lawyer and habitué of the Catskill Mountain House—got into a row with the hostelry’s grouchy proprietor over broiled chicken. He requested some for his daughter, who was on a restricted diet due to her health. According to an account in the New York Times more than twenty years later, guests at the Mountain House in those days had to take what they were served for dinner—or go to bed hungry. The lawyer attempted to reason with his stiff-necked host: “Broiled chicken is the only thing the child can take.” “No!” was the reply. “There is no chicken on the bill of fare to-day.” “Can’t you send out and kill a chicken?” asked the reasonable lawyer. Again the reply: “No!” “Well, then,” said the now huffy Mr. Harding, “I will build a hotel where I can get chicken when I want it.” And so he did.

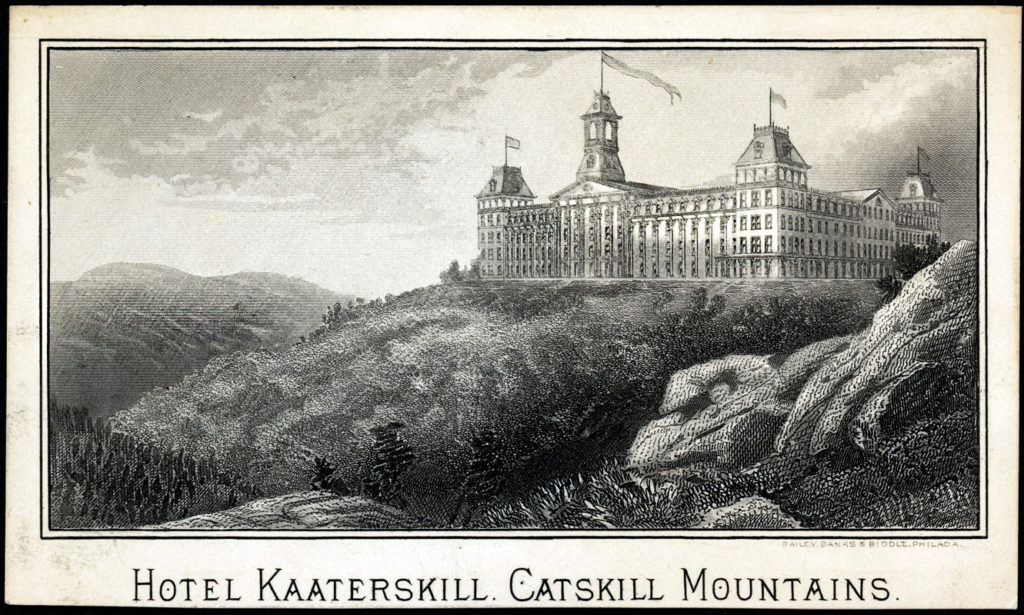

Mr. Harding marched over to Ira Scribner’s place nearby and bought all of Palenville Mountain from him for six thousand dollars. He then engaged the services of hundreds of local day laborers and carpenters to construct—in less than a year—what would become the world’s largest wood frame structure, along with a marvelously-engineered new road up the face of the mountain. The landscape artist Jervis McEntee happened by the site on June 1, 1881, just weeks before Hotel Kaaterskill’s scheduled opening. “It’s an immense affair,” he wrote in his diary, “but no where near finished.” Ah, but where there’s a well-funded will, there’s always a way. Contrary to all expectations—except those of Mr. Harding—the new hotel was completed on schedule. On June 26th, 1881, Hotel Kaaterskill opened its doors to a throng of well-paying guests. And from that day on, broiled chicken was available anytime to anyone who wanted it, not to mention a good, stiff drink at the hotel’s well-stocked bar.

Within just a few years, Hotel Kaaterskill—“the grandest and loftiest hotel in America”—became the premier mountain resort in the Catskills, literally and figuratively overshadowing its venerable neighbor, the Mountain House, which sat nearly three hundred feet lower in elevation. During the high season of summer, anybody who was anybody—presidents and former presidents, distinguished military men, discerning literary celebrities—could be found vacationing at Hotel Kaaterskill. Up to 1100 guests could be accommodated, along with a resident staff numbering in the hundreds. In July 1886, Mr. Harding celebrated his success by hosting an all-expense-paid “editorial excursion party” for journalists from the most prestigious newspapers. His hope was that they would sing the praises of his fabulous hotel. The writer from the New York Times was happy to oblige. He described the hotel as “a city in itself,” effusing over its many amenities, including the 648 “sleeping rooms,” each of which was “deliciously airy,” and the sizeable kitchen, “clean as snow,” with floors “kept as spotless as the most fastidious housewife could desire,” and the “dishwashing department” which was “like a factory unto itself,” where “half a dozen women stand on one side of a row of sinks and wash,” before they “pass the dishes across to the other side, where another corps wipes them,” after which the dishes are handed off “to another corps, which polishes them up, sorts them out, and passes them along to another lot of people, by whom they are placed in steam heated closets to be kept warm and ready for use.” The Times correspondent goes on to extoll “the separate room for the making of salads,” where there was “one man cleaning lobsters and another cleaning chickens, and two others making them into salads as fast they were ready,” nearby to which was “a large refrigerator room, where poultry is kept on ice.” And on the other side of the kitchen was “the meat room, where 14 days’ stock is always kept on hand . . . a great refrigerator room in which hang rows upon rows of shoulders, quarters, and ribs.” The meat room employed “two butchers, who cut up the meat and prepare it for the kitchen. As they finish up their work they place the steaks and chops and cuts in neat layers on strata of ice in big ice boxes. Fish is also prepared in this room, as well as clams.”

neighbor, the Mountain House, which sat nearly three hundred feet lower in elevation. During the high season of summer, anybody who was anybody—presidents and former presidents, distinguished military men, discerning literary celebrities—could be found vacationing at Hotel Kaaterskill. Up to 1100 guests could be accommodated, along with a resident staff numbering in the hundreds. In July 1886, Mr. Harding celebrated his success by hosting an all-expense-paid “editorial excursion party” for journalists from the most prestigious newspapers. His hope was that they would sing the praises of his fabulous hotel. The writer from the New York Times was happy to oblige. He described the hotel as “a city in itself,” effusing over its many amenities, including the 648 “sleeping rooms,” each of which was “deliciously airy,” and the sizeable kitchen, “clean as snow,” with floors “kept as spotless as the most fastidious housewife could desire,” and the “dishwashing department” which was “like a factory unto itself,” where “half a dozen women stand on one side of a row of sinks and wash,” before they “pass the dishes across to the other side, where another corps wipes them,” after which the dishes are handed off “to another corps, which polishes them up, sorts them out, and passes them along to another lot of people, by whom they are placed in steam heated closets to be kept warm and ready for use.” The Times correspondent goes on to extoll “the separate room for the making of salads,” where there was “one man cleaning lobsters and another cleaning chickens, and two others making them into salads as fast they were ready,” nearby to which was “a large refrigerator room, where poultry is kept on ice.” And on the other side of the kitchen was “the meat room, where 14 days’ stock is always kept on hand . . . a great refrigerator room in which hang rows upon rows of shoulders, quarters, and ribs.” The meat room employed “two butchers, who cut up the meat and prepare it for the kitchen. As they finish up their work they place the steaks and chops and cuts in neat layers on strata of ice in big ice boxes. Fish is also prepared in this room, as well as clams.”

With so many guests—plus the considerable resident staff needed to keep them happy—the hotel complex included “a very large laundry facility situated some distance away to the rear.” During his visit in June 1881, Jervis McEntee observed the laundry building—comparable in extent to a good-sized boardinghouse—under construction. It was going up on the very spot where he and his fellow landscape artists used to find inspiration for their paintings. “We returned by the Sunset Rock path to the Fairy Spring and so around by the path above Druid rocks until we struck the iron pipe by which water is to be forced to the hotel, which we followed down to the brook at the upper end of Scribner’s first field, where they are building a reservoir and a large laundry right in the track where Sanford, Whittredge and I used to go sketch along the stream.” A formerly picturesque scene had been rendered into a construction site.

Hotel Kaaterskill’s new steam-laundry soon became a veritable industrial operation, powered by an immense woodfired boiler that required a steady input of four-foot logs. A team of five men took care of that as well as all things mechanical in the plant. Meanwhile, the bulk of the laundry work itself was handled by a resident staff of twenty-five women. Although no firsthand account of the labor conditions in this particular steam-laundry is available, a good picture of what it might have been like is found in the journalist Rheta Childe Dorr’s autobiography, A Woman of Fifty. In 1907 she worked undercover for a brief stint at a steam-laundry in the city. As she describes it, the “women did no washing. Machinery, men-tended, did all that. Women did the jobs men scorned to do. Women handled soiled, sometimes disgustingly soiled clothes, marked them and sorted them in piles for the washing machines.” The boiled clothes, tablecloths, and bedsheets emerged from the vats of lye soap and were fed into mangles, then separated and sorted out for ironing. The environment inside the laundry building was deafening, dark, and hot. “Worst of all was the speed, on which the forewoman insisted, and the deadly monotony of the task. Bend, untwist, shake; bend, untwist, shake; bend, shake; bend, shake, hours unending. Flap, flap, flap—shuffle of feet on the water-soaked floor. A snatch of talk, a curse, a shriek of nervous laughter, muffled by the eternal flap, flap, flap.”

In August of 1904, the laundry plant at Hotel Kaaterskill caught fire from an overheated stove and burned to the ground. No lives were lost and a new building was quickly put up in its place, which continued to operate until September 8, 1924. That’s when Hotel Kaaterskill itself caught fire and burned to the ground, purportedly the result of soapmaking activities in the kitchen. That soap might well have been intended for use down at the steam laundry.

These days, the site once occupied by Hotel Kaaterskill has returned to forest and is managed as a state park. Bits of crockery, broken toilets, and twisted scraps of metal still litter the ground, but you have to poke around among high weeds to see them. A mile or so in the direction of Ira Scribner’s old boardinghouse—itself long since vanished from the landscape—stand the lonesome stone ruins of the steam laundry and the mucky remnants of the reservoir built to supply the water. This location too has been reclaimed by forest, though it’s unlikely to attract the eye of any landscape artist. The place seems suffused with a faint sadness.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on July 20, 2018