Helderberg Castle

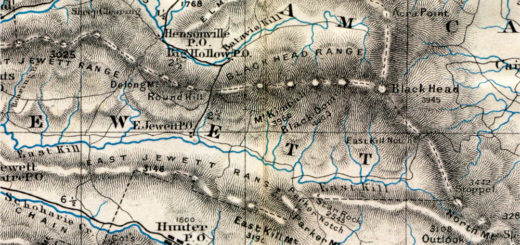

From a certain vantage point along the road coming out of New Salem in Albany County, you can catch a glimpse of them up there—the castle ruins. Perched on the rim of one of the higher cliffs of the Helderberg escarpment, they lie a couple miles south of Thacher State Park. The man who built this wildly weird and wayward structure is long dead. Whatever hold his name has on living memory fades with each passing year. Soon the only traces of Bouck White—self-styled “Hermit of the Helderbergs”—will be found in moldering newspaper clippings, seldom-consulted local history books, and sketchy postings on the internet.

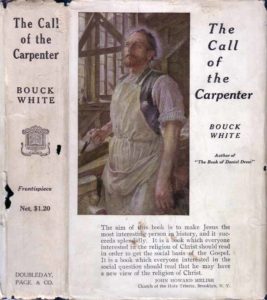

Charles Browning White was born in 1874 in the Schoharie County town of Middleburgh. Early on, friends and family started calling him by his mother’s maiden name, Bouck. He graduated from the local school and went to Harvard to study journalism. After a brief stint working for newspapers, he entered the seminary and became a minister. He did not give up on his writing. In 1903 he published his first book, Quo Vaditis? A Call to the Old Moralities. It reads as a sort of hectoring prose poem, abounding in passages such as: “America is sick with the sickness known as Too-much” and “America is a church of God, and the ballot-box a yearly sacrament.” Pithy bombast became his trademark style. The best known of his books—The Call of the Carpenter (1913)—portrays Jesus of Nazareth as a working-class rabble-rouser. In a sequel titled The Carpenter and the Rich Man, the author proclaims: “The cult of wealth is a plague so pestilent that the strictest quarantine must be established against it.” He relished quoting scripture to his own good ends. “Wealth is an impregnable castle, in the imagination of a rich man.”

the local school and went to Harvard to study journalism. After a brief stint working for newspapers, he entered the seminary and became a minister. He did not give up on his writing. In 1903 he published his first book, Quo Vaditis? A Call to the Old Moralities. It reads as a sort of hectoring prose poem, abounding in passages such as: “America is sick with the sickness known as Too-much” and “America is a church of God, and the ballot-box a yearly sacrament.” Pithy bombast became his trademark style. The best known of his books—The Call of the Carpenter (1913)—portrays Jesus of Nazareth as a working-class rabble-rouser. In a sequel titled The Carpenter and the Rich Man, the author proclaims: “The cult of wealth is a plague so pestilent that the strictest quarantine must be established against it.” He relished quoting scripture to his own good ends. “Wealth is an impregnable castle, in the imagination of a rich man.”

Over the years leading up to the Great War, White was an active member of the Socialist Party—until he was “read out” for his uncompromising religious views. He had the audacity to insist that the poor be allowed to worship side by side in the same churches as the rich. Harboring such radical views led to his being unfrocked, so he started his own church and called it the Church of the Social Revolution. He preached that Jesus was a doer, and so he became one himself. He spent six months in jail for disrupting services at the Manhattan church attended by John D. Rockefeller and his family. Another time he led a public burning of flags from nine different nations, including the United States. He claimed the action was not desecrating but symbolic: the resulting heap of ashes represented all nations having “become one.” The New York City police thought otherwise. They threw him into jail for thirty days, prompting Eugene Debs to call him “the only Christian minister in New York.”

By the close of the war, White had grown disillusioned with organized social activism. In 1921, he traveled to Paris and met a nineteen-year-old woman who agreed to marry him and join him on his “mountain estate” in the town of Marlborough on the Hudson. Within days of her arrival, she realized her mistake. As reported in the New York Times, White’s “estate” turned out to be little more than a “tumbled down farm house of diminutive dimensions; a tangled plot of thirty acres near jungle, rocks, and quietness; a flock of five white Leghorn hens, a discouraged pig, one cow and an elderly ‘flivver.’” All of this White now referred to as his “monastic retreat.” He commenced tutoring his young wife in proper political theory and introduced her to his radical associates. He told her that she must embrace his doctrines and serve as his “prophetess.” He expected her to survive on the same diet of fried eggs, milk, and rancid butter that sustained him. But all she wanted was a gentlemanly husband and a nice home. When she expressed her skepticism, he beat her and said she needed to become as obedient as his cow. When the townspeople got wind of this, a posse dropped by his house and proceeded to tar and feather him, and just for good measure they threw him into a lake. The incident made the front page of the Times. Soon enough the marriage was annulled and White fled town. The headline the next day read: “Bouck White Sells His Cow, Closes Home.”

By the close of the war, White had grown disillusioned with organized social activism. In 1921, he traveled to Paris and met a nineteen-year-old woman who agreed to marry him and join him on his “mountain estate” in the town of Marlborough on the Hudson. Within days of her arrival, she realized her mistake. As reported in the New York Times, White’s “estate” turned out to be little more than a “tumbled down farm house of diminutive dimensions; a tangled plot of thirty acres near jungle, rocks, and quietness; a flock of five white Leghorn hens, a discouraged pig, one cow and an elderly ‘flivver.’” All of this White now referred to as his “monastic retreat.” He commenced tutoring his young wife in proper political theory and introduced her to his radical associates. He told her that she must embrace his doctrines and serve as his “prophetess.” He expected her to survive on the same diet of fried eggs, milk, and rancid butter that sustained him. But all she wanted was a gentlemanly husband and a nice home. When she expressed her skepticism, he beat her and said she needed to become as obedient as his cow. When the townspeople got wind of this, a posse dropped by his house and proceeded to tar and feather him, and just for good measure they threw him into a lake. The incident made the front page of the Times. Soon enough the marriage was annulled and White fled town. The headline the next day read: “Bouck White Sells His Cow, Closes Home.”

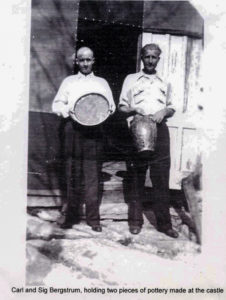

After his brief marital adventure, White laid low for a few years in New England, where he became a potter. As one reporter noted: “The unfrocked pastor has turned from the social revolution to the revolution of the potter’s wheel.” By the mid-twenties White had returned to Paris, where he stayed for several years, perfecting a method of pottery glazing that required no heat. He called his invention “Bouckware.”

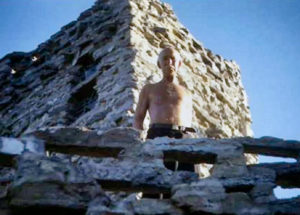

Along about 1933, White had returned to the States and acquired five acres of rocky land high in the Helderbergs. It was a place he remembered fondly from his youth. With the assistance of a pair of brothers from Sweden, he built a castle for himself, by hand, out of the native limestone bedrock. He lived in this structure—which he called “Federalburg”—for the duration of the Depression, making and selling his Bouckware pottery to tourists who came from miles around just to see this unusual American who formerly preached a gospel of voluntary poverty and now lived in a castle. Alas, this blissful existence came to an end in 1942, when the sixty-eight-year-old White suffered a debilitating stroke, curtailing any further pottering around in his castle. He was forced to sell the property and take up residence at the Home for Aged Men in suburban Menands.

pair of brothers from Sweden, he built a castle for himself, by hand, out of the native limestone bedrock. He lived in this structure—which he called “Federalburg”—for the duration of the Depression, making and selling his Bouckware pottery to tourists who came from miles around just to see this unusual American who formerly preached a gospel of voluntary poverty and now lived in a castle. Alas, this blissful existence came to an end in 1942, when the sixty-eight-year-old White suffered a debilitating stroke, curtailing any further pottering around in his castle. He was forced to sell the property and take up residence at the Home for Aged Men in suburban Menands.

As if the gods were conspiring against him, a fire broke out in December, 1944, engulfing the wooden portions of the castle, rendering it a ruin. Afterwards a reporter from the Associated Press visited White in what she described as his “skimpy room” in the home for the aged. She asked him how he felt about his dream going up in smoke. His wistful response: “My conflagration is hardly worth noting, in view of the world conflagration.’” Two and a half years later—on January 7, 1951—Bouck White passed away in his skimpy old man’s room in suburban Menands.

Over the years, the ruined castle and the various other buildings on the property were bought and sold several times, renovations made. As reported in the Altamont Enterprise on August 22, 1947: “Remaining in charge of the pottery shop during the successive changes of ownership is Sigurd Bergstrom, who went there to live with Mr. White in 1933, and to him White confided the secret of his “flexible glaze” pottery.” At some point, the business was finally shuttered, the secret never divulged, and the place became strictly a private residence. Owners came and went. One of them—as she was putting the property on the market—expressed regret for ever having acquired such a “money pit.”

Nevertheless, Helderberg Castle remains in private hands to this day. Curiosity-seekers are not welcome. Along the approach to the grounds, formidable albeit fading signage warns off visitors and serves as a reminder: It’s not just in imagination that a castle is impregnable.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on April 27, 2018