Frederic Church’s Olana; or, Home Is Where the Art Is

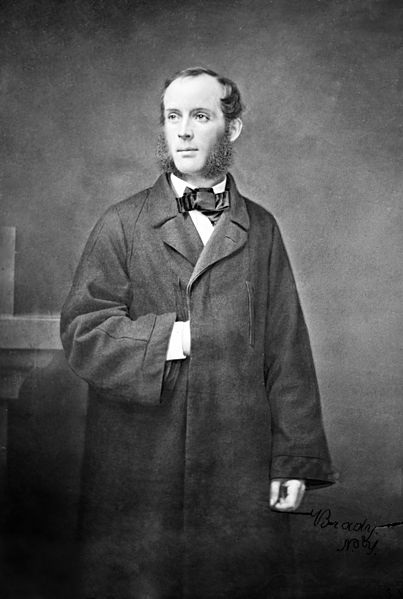

Frederic Edwin Church was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1826. At a young age, he expressed passionate interest in becoming a landscape artist. His father, Joseph—a silversmith by training and later a founder and director of the Aetna Insurance Company—was not keen on the idea. Yet young Frederic persisted and his father relented. Arrangements were made for young Frederic to study with the best teacher money could buy. In early June of 1844, the eighteen-year-old Church made his way to Catskill, New York to pursue a two year course of study with the most famous artist in America. His name was Thomas Cole.

Prior to setting out for the Hudson Valley, Church had written a letter to his new mentor in which he vowed “to exert myself in your art to the extent of my ability,” adding that “my highest ambition lies in excelling in the art; I pursue it not as a source of gain or merely as an amusement, I trust I have higher aims than those.” Words any teacher would be grateful to hear—but also words that Church lived up to. The eager student got right to work, sketching a variety of subjects across his teacher’s home turf, including scenes around the Catskill Mountain House high up on the eastern escarpment of the range. Cole quickly recognized that his protégé was in fact a budding artistic genius. The teacher-student relationship gave way to an artistic friendship. At the end of his two-year stint with Cole, Church moved to New York City and launched his own career. By age thirty-three, he had become the most famous artist in America. As well as the most successful. His canvases, some of them colossal in size, commanded colossal sums. Take, for example, his “Heart of the Andes.” In 1859 it sold for $10,000, the highest price ever paid for a painting by a living American artist. Joseph Church’s early misgivings about his son’s choice of career had proven ill-founded. Frederic was indeed his father’s son.

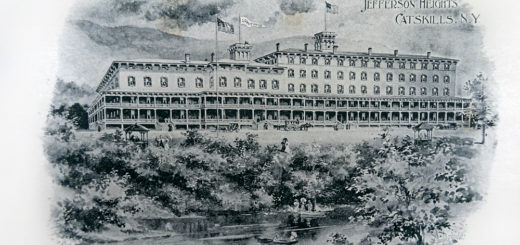

Using some of the wealth earned from his work, Church in 1860 bought 120 acres of farmland along the base of a hill on the opposite side of the river from Catskill. It was a place he knew well—Cole used to take him there on sketching expeditions. A few months after buying the land, Church married Isabel Carnes and erected a modest house in which to raise a family. They called the place “Cosy Cottage.” Over the next several years, Church bought up other parcels around the hill until he owned it to the very top. On that spot he built a substantial house, which locals still refer to as “the Castle.” He designed it himself and described it as “Persian in style adapted to the climate and requirements of modern life.” But just to make sure it wouldn’t one day come tumbling down on him and his family, he brought in the prominent architect Calvert Vaux as a consultant. Vaux, as it happens, was married to Mary McEntee, sister of the artist Jervis McEntee. Among his many accomplishments, Vaux co-designed Central Park with Church’s cousin Frederick Law Olmsted. By the latter part of 1872, work on the main house at Olana had progressed sufficiently so that the family could move in to the second story. It took another four years to finish the extensive interior woodwork and painted decoration that—to this day—adorns the first floor.

When Church started construction on his grand house on the hill, his productivity as a painter had fallen off considerably due to rheumatoid arthritis. To compensate, he redirected his creative energy into architectural pursuits—designing both the house and the 250 acre landscape surrounding it. As he described the situation in 1877: the “interior decorations and fittings are all in harmony with the exterior architecture. It stands at an elevation of 600 feet [actually just under 500 feet] above the Hudson River and commands beautiful views of sky, mountains, rolling and savannah country, villages, forest and clearings. The noble River expands to a width of over two miles forming a lakelike sheet of water which is always dotted with steamers and other craft.” To his good friend, the renowned sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer, Church wrote: “About an hour this side of Albany is the Center of the world—I own it.” It was probably intended as tongue-in-cheek understatement. And it should be acknowledged that, since 1966, the people of the State of New York own it.

By the late 1880s, Church’s rheumatoid arthritis had become crippling, but his passion to design and create remained robust. In the summer of 1888, he set to work on a major addition to the main house at Olana: a commodious studio wing along with a spacious connecting corridor and downstairs guest bedroom. “I would be desperately lonely,” he wrote to his friend Charles Dudley Warner, “if I were not building a studio in the rear of my House. I can fancy the thought now passing your mind—‘Building a Studio at his age and with his infirmities!’ Well, we will call it a Mausoleum. It is a suitable shell for all the Pharaohs. It is very interesting work anyhow and our Verandah makes a capital stage for overlooking the work as it progresses.” Church did indeed spend lots of time on that verandah, not only overlooking the work but directing it. This time he did not engage a consulting architect. As he explained to Palmer: “I am of course very busy superintending the New Studio. It takes a great deal of time and no little study to keep so many men at work advantageously— As I have no regularly drawn plans I have to explain every detail. It is not a little difficult I find to keep the work going economically when none of the men really know what is coming next.” To another he made the wistful remark: “I wonder whether I shall work as hard in the new studio as I do in erecting it.”

Though it took two years, the new studio was finished by the end of summer 1890. In December of that year, Church wrote to Jervis McEntee: “My new studio is in working order and last week I applied the first dab of color. It was on one of my old pictures which I recently bought at the Sale of Dr. Otis’ collection . . . . I was glad to get the picture because it is a view from my Place.” This inaugural picture Church set to work on in his brand spanking new studio was titled “Catskill Mountains from the Home of the Artist.” He felt it needed a little touching up. Originally he had painted it to order in 1871 for his friend Fessenden Nott Otis, a notable New York City physician and patron of the arts. The two men seem to have been close. Records indicate that Otis served as the Church family physician when they were in the city. He and Church were among the founders of the Metropolitan Museum. Otis also had strong ties to the region. His wife was from Catskill and he spent considerable time there during the latter decades of his life. When he died on May 24, 1900—just six weeks after Church himself passed—his remains were brought to the village and he was buried in the Thomson Street Cemetery, not far from the grave of Thomas Cole. That Church went out of his way to reacquire this particular work—almost twenty years after painting it—suggests an abiding affinity for what it represents.

“Catskill Mountains from the Home of the Artist” was executed while the main house was being built. It displays a glorious autumn view, generally looking westward from the top of Church’s hill across the Hudson River toward the mountains. A half-halo of golden light from the setting sun suffuses the left side of the picture, where on the actual landscape Thomas Cole’s house and studio would have stood. But here in the radiant middle ground of the painting, instead of a mimetic representation we perceive something like the lambent memory of Cole himself and the influence he still wields over landscape art in America.

When Church brought this picture back home, a dozen or so painted views of Olana—most of them done by his own hand—already hung on the walls of the house. “Catskill Mountains from the Home of the Artist” would now be the largest of them all. Add to that several sizable, strategically-placed windows in the house that face out upon and frame the very scenes that inspired these paintings—and something like a mise en abyme of décor opens up. Visitors to the house—both then and now—are drawn into a visual call-and-response, an ingenious orchestration between interiors and exteriors, between dabs of paint on canvas and the actual shimmering mountains and waters visible through the enormous panes of glass, between the luminous figures of the artist’s imagination and the effulgent figures of one’s own. All of this composed by an artist who—in the thrall of debilitating illness—fashioned for himself a magnificent studio in which he would create few additional works in the decade remaining to him. Yes, call it a “mausoleum” as its designer suggested, but recognize too that it’s a rousing mausoleum—with innumerable views opening out upon the “Center of the world.” And we own it.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on May 3, 2019