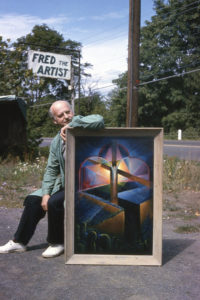

Fred the Artist

The artist Fred De Sawal had his studio in a ramshackle cottage along old Route 23 in Leeds, New York. It was located not far from the Jolly House resort, where some of his paintings would be kept on display. In this way a few sales were generated, but most of his works were sold directly out his studio. Passing motorists on their way to a good old-fashioned Catskill Mountain vacation would stop in, lured by the simple homemade sign he had placed near the road. In plain letters, it read “Fred the Artist.”

De Sawal’s imagination was engaged by a variety of subjects, ranging from traditional still lifes to Civil War battle scenes to surrealistic extravaganzas. But he is best remembered for his quiet, luminist landscapes that have an obliquitous, slightly uncanny, Catskill Mountains feel to them—as if Thomas Cole had been channeled through Kay Sage with a little John Kensett added for good measure. It is regrettable that his work is not better known, at least here in the region that inspired him.

Biographical information for De Sawal is hard to come by. He was born in London in 1912, of French-German descent. When he was in his teens, his family moved to the United States. He attended art school at Cooper Union in New York City, and afterwards continued his training in Germany and France. He returned to the States and settled in Brooklyn, working for a number of years at Homart Studios on Atlantic Avenue. Eventually, he moved to the Catskills and opened his own studio, where he worked for the rest of his relatively short life, dying in 1966 at the age of 53.

I visited Fred De Sawal’s studio when I was a small child. Those visits are among my earliest memories. I was taken there by my parents, who had seen some of his paintings at the Jolly House and were interested in acquiring one for themselves. The studio was surprisingly dim and redolent of linseed oil. Canvases—both framed and unframed—covered the walls. The artist himself seemed to me a very old man, though he was probably ten years younger than I am today. I remember my father being quite taken by one painting in particular, a winter scene with a cold blue pond in the foreground, then some woods that looked very much like our woods up in the mountains, and then—somewhat obscured by the bare limbs of the trees—a snowy mountain that looked very much like the mountain we could see from our land, where someday we would build a dream house. My father bought the painting, for how much I don’t know. This picture, said my father, will look perfect, someday, hanging above the fireplace in the dream house when we get it built. In the meantime, for many years, it hung in the living room of our ordinary house in an lackluster suburb in New Jersey. Growing up, I spent many an idle hour gazing into that enticing scene, tranquil as it was austere, dreaming of a Land in the Sky. I guess you could say that the painting served as an emergency exit for my imagination.

I visited Fred De Sawal’s studio when I was a small child. Those visits are among my earliest memories. I was taken there by my parents, who had seen some of his paintings at the Jolly House and were interested in acquiring one for themselves. The studio was surprisingly dim and redolent of linseed oil. Canvases—both framed and unframed—covered the walls. The artist himself seemed to me a very old man, though he was probably ten years younger than I am today. I remember my father being quite taken by one painting in particular, a winter scene with a cold blue pond in the foreground, then some woods that looked very much like our woods up in the mountains, and then—somewhat obscured by the bare limbs of the trees—a snowy mountain that looked very much like the mountain we could see from our land, where someday we would build a dream house. My father bought the painting, for how much I don’t know. This picture, said my father, will look perfect, someday, hanging above the fireplace in the dream house when we get it built. In the meantime, for many years, it hung in the living room of our ordinary house in an lackluster suburb in New Jersey. Growing up, I spent many an idle hour gazing into that enticing scene, tranquil as it was austere, dreaming of a Land in the Sky. I guess you could say that the painting served as an emergency exit for my imagination.

To provide escape for the weary soul is but one purpose of art, and perhaps—as some regularly argue—the least important one. Nevertheless, landscape paintings have been providing imaginative refuge to Americans for a very long time, at least since Thomas Cole sold his “Falls of Kaaterskill” to Colonel John Trumball—veteran of the Revolutionary War and artist himself—in 1826. Less than two decades later, a prominent member of the American Art-Union went so far as to proclaim the necessity of art for assuaging the “jealousies, and commercial anxieties, and competitions” of his fellow industrialists and entrepreneurs. “Our institutions keep us politically and socially in a state of perpetual excitement and competition. President-making, and money-getting, together, stir up all that is bitter, sectional, or personal in us. We want some interests that are larger than purse or party, on which men cannot take sides, or breed strifes, or become selfish. Such an interest is Art.” Of course the art world has never been without its own factions and “strifes,” but who among us today in 2018 is not in need of a little relief from “president-making” and “money-getting” not to mention “all that is bitter, sectional, or personal in us”? Why not seek, if only for a short spell, deliverance in a work of landscape art? Or better yet, by taking an excursion out into the realm that inspired that art.

To provide escape for the weary soul is but one purpose of art, and perhaps—as some regularly argue—the least important one. Nevertheless, landscape paintings have been providing imaginative refuge to Americans for a very long time, at least since Thomas Cole sold his “Falls of Kaaterskill” to Colonel John Trumball—veteran of the Revolutionary War and artist himself—in 1826. Less than two decades later, a prominent member of the American Art-Union went so far as to proclaim the necessity of art for assuaging the “jealousies, and commercial anxieties, and competitions” of his fellow industrialists and entrepreneurs. “Our institutions keep us politically and socially in a state of perpetual excitement and competition. President-making, and money-getting, together, stir up all that is bitter, sectional, or personal in us. We want some interests that are larger than purse or party, on which men cannot take sides, or breed strifes, or become selfish. Such an interest is Art.” Of course the art world has never been without its own factions and “strifes,” but who among us today in 2018 is not in need of a little relief from “president-making” and “money-getting” not to mention “all that is bitter, sectional, or personal in us”? Why not seek, if only for a short spell, deliverance in a work of landscape art? Or better yet, by taking an excursion out into the realm that inspired that art.

Today that winter scene by Fred De Sawal that so captured my father’s fancy hangs in the dream house that at last got built. My wife and I live in it today. I still gaze into the depths of that painting from time to time, but more often than not I simply look out the window and take in the scene it always reminded me of. Today the woods are thicker and much taller than they used to be. The mountain in the distance is no longer visible, thanks to the succession of forest trees. “Art improves nature,” they used to say. I don’t know about that, but a good landscape painting does open vistas not ordinarily perceived. However fleeting such vistas are, they may in the end prove superior to all our president-making and money-getting.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on July 27, 2018