Following Stones

A long walk out old Barnum Road in East Jewett takes you nowhere in particular. It begins as a trail where the maintained town road ends but soon fades into little more than a vague track. Nothing much to see out there anymore. In former times, though, a few widely spaced hill farms were making a go of it, but they have long since vanished. All that remains of human presence is a tumbling abandonment: empty foundations and long lines of dry laid stone wall marking the bounds of bygone pastures. These forsaken lines run for miles through darkening woods. Who knows where they lead?

* * *

In colonial times, a number of early English travelers in New England and eastern New York commented on the large, curious heaps of stone and brush they encountered during their travels. The earliest mention comes from the Hudson Valley. In 1686, an English Governor named Thomas Dongan granted a large patent of former Mohican lands to Robert Livingston. The document describes a boundary marker on the north line of the patent that was located at “a place called by the natives Wawanaquiasack, where the Heapes of Stones Lye being near the head of a Certaine kill or creek called Nanapenahekan . . .lying near unto the said hills of the said heaps of Stones upon which the Indians throw upon another as they Passe by from an Ancient Custom amongst them.” Similar accounts of stone tossing can be found throughout the annals of colonization.

* * *

Elmer Barnum Road is a town-maintained thoroughfare that starts in Maplecrest and dead ends in East Jewett. The road’s namesake was born in 1898 and raised in a house that still stands. He lived there for most of his life and never married. Although he had the power of speech, he chose not to use it, until his last years. He played the guitar and rode a motorcycle. Children enjoyed his company. He died in 1978 and is buried in Maplecrest Cemetery.

* * *

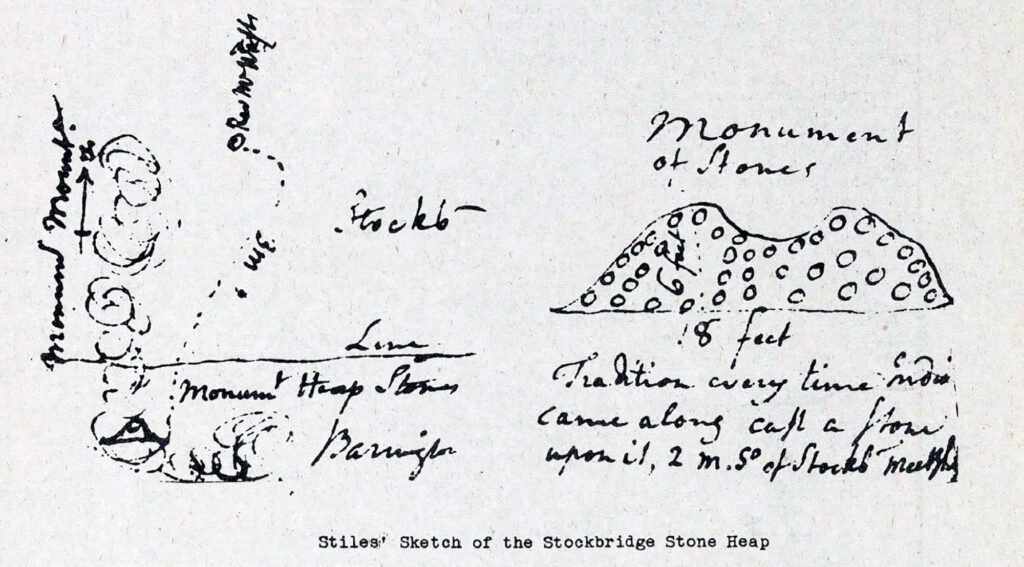

In 1734, the Rev. John Sergeant, traveling through the Berkshire hills with an Indian guide and interpreter by the name of Poo-poo-nuck, came upon an extensive pile of rocks just a couple miles south of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. As he described it in his journal: “There is a large heap of stones, I suppose ten cart loads, in the Way to Whan-tu-kook, which the Indians have thrown together, as they passed the place; for it used to be their custom, every time one passed by, to throw a stone to it.” When he asked around among the people living at the village why they followed this particular custom, they replied “what was the end of it, they cannot tell; only say their Fathers us’d to do so and they did because it was the custom of their fathers.” Only one of the people Sergeant asked—a Mohican guide named Ebenezer—dared an explanation, saying that “he supposed it was design’d to be an expression of their gratitude to the Supreme Being, that he had preserv’d them to see the place again.” Almost thirty years after John Sergeant’s account, the Rev. Ezra Stiles visited the same heap and drew a sketch labeled “Monument of Stones.” Stiles records the diameter of the pile as eighteen feet.

* * *

Elmer Barnum’s stone stands out prominently among the others in Maplecrest Cemetery for its color: a lichen-encrusted pink amid a throng of teetering grays. He is buried next to his parents, Martin Barnum and Carrie Jane Foster Barnum. Further off is the monument marking the grave of Elmer’s grandparents, Bethuel Barnum and Phoebe Julia Shoemaker Barnum. To follow this particular line of family stones any further, one must travel to the Little West Kill Cemetery, on the other side of the Mountaintop. There among several other Barnum stones is the one that marks the grave of Elmer’s great-grandmother, Sarah Jemima Steward Barnum. No sign of where her husband might lie. He outlived her by many years and went on to marry again.

* * *

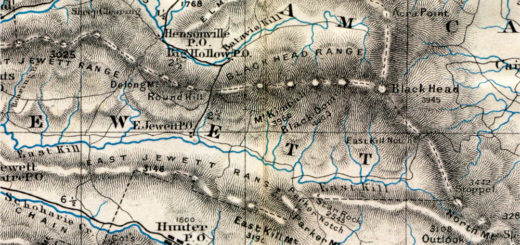

At the end of the 18th century, the Rev. Gideon Hawley noted—after many years of living among the Algonquin peoples—that he had “observed in every part of the country, and among every tribe of Indians” similar heaps of stones and sticks. And this custom of heap-making was by no means limited to the Algonquins. In 1753 young Rev. Hawley made a trip to the “Schoharry” country accompanied by a Mohawk guide. At one point along the way—in the vicinity of today’s town of Esperance—“We perseaved our Indian looking for a stone, which having found, he cast to a heap, which for ages has been accumulating by passengers like him, who was our guide.” When Hawley asked the man “why he observed the rite,” he received no reply. The Mohawk “did not like to talk on the subject.” In later years, after witnessing innumerable examples in other places of the same practice of heap-making, Hawley concluded: “This custom or rite is the acknowledgement of an invisible being. We may style him ‘the unknown God’, whom this people worship. This heap is his altar. The stone that is collected is the ablation [sic] of the traveller, which, if offered with a good min, may be as acceptable as a consecrated animal.” Then he adds: “perhaps these heaps of stone may be erected only to a local deity, which most probably is the case.”

* * *

An anonymous author of 1802 speculated that the Indian stone heaps “may be nothing more than an offering made to good luck, a mysterious agent, which is scarcely considered as a deity, which is spoken of without reverence, and adored without devotion.”

* * *

In the latter half of the 20th century, an archaeologist remarked: “The blanks which the white men drew in their attempts to solve the riddle of the stone heaps bothered them. It was so simple—no self denial, no mutilation, no real offering or gift, no wails of atonement—just the more or less surreptitious dropping of a stone or piece of brush in an out-of-the-way place! Many made their own interpretations when concrete answers were not forthcoming from the natives. Some saw in the practice a form of worship, others a hidden idolatry, or an attempt at propitiation by sorcery or magic.”

* * *

In the Book of Genesis it is written: “And Laban said to Jacob, Behold this heap of stones, and behold this pillar, which I have cast betwixt me and thee: This heap be witness, and this pillar be witness, that I will not pass over this heap to thee, and that thou shalt not pass over this heap and this pillar unto me, for harm.”

* * *

In his monumental Travels in New-England and New-York, the Rev. Timothy Dwight recounts revisiting the Stockbridge stone heap in 1811, after last having seen it many years earlier. “On our way to Stockbridge we went to the Indian monument, mentioned in a former part of these letters; and, to our great regret, found it broken up . . . . I ought, in my account of that, to have added, that this mode of erecting monuments was adopted only on peculiar occasions. The common manner of Indian burial had nothing in it of this nature. The remains of the dead, who died at home, were lodged in a common cemetery, belonging to the village, in which they had lived.” The Indian dead were interred with various items deemed to be useful “to their departed friends, in their journey towards that happy region in the South-West; where, according to their Mythology, all the brave and good will be finally gathered. It is remarkable, that they erected no monuments over them, nor commemorated them by any external objects whatever. Instead of this, they would never themselves name them, nor without resentment suffer them to be named by others.”

* * *

At the back of the Maplecrest Cemetery is an iron bench painted white. Behind it is a stone wall with a few toppled markers leaning against it. Beyond the wall flows the Batavia Kill, a stream the Mohawks called Chaw-tick-ag-nack.

* * *

In recent decades, the pastime of cairn-building or rock-stacking has exploded among outdoor recreationists. While most of these rock pilers do it “just for fun,” there are a few who perform it as a “spiritual practice.” No surprise then that this contemporary heaping of stones should be met with a backlash. These days there are plenty of cairn-haters out there, both on the ground and on the internet. They believe cairns are intrusive man-made objects that detract from one’s experience of nature. “Preserved lands” are regarded as sacred space. Indeed, wilderness is defined by Federal law as “land untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Cairn-haters decry what they perceive to be a pernicious influence. As explained on the internet: “Instead of having to utilize your skills and prowess as an outdoorsy person, cairns allow you to sheepishly follow those who have come before. No critical thinking, maps, compasses, or triangulation, just the mundane and thoughtless process of looking for piles of stones.” Leave no trace, the cairn-haters say. “The creation of cairns is the physical manifestations of our selfish desires to leave a mark on the environment!!! We go into nature to escape human impact, not to be constantly reminded of its presence.” You find this sentiment formalized in one of the rules of an influential hiking club: “No cutting, cairn building, blazing, trail building or otherwise marking paths.” A very different attitude, it would seem, from that of the native people who made the stone heaps.

* * *

By 1840, the stone heap near Stockbridge had been obliterated from the landscape entirely. The many tons of rock that had given it form had been incorporated into a farmer’s stone wall. A local historian notes: “A search was made for buried trinkets, but without any reward ….” This is in keeping with what happened at the countless other Indian stone heaps dismantled by relic hunters: No bones, no trinkets, no treasure was ever found.

* * *

As the years and decades roll on, the lines engraved on the stones in Maplecrest Cemetery become harder and harder to read. Legibility is as fleeting as the flowers and flags placed on the graves.

* * *

When we were kids, somebody told us a story of hidden treasure and we believed it. To the best of my recollection, the story went like this. A Prohibition-era gangster by the name of “Gentleman Jack” was friendly with some of the locals in Maplecrest. After a big heist, he needed a good place to stash the loot. Someplace nobody would think to look. A place just like what’s out there along old Barnum Road! Even by the Roaring Twenties it had already become a forgotten precinct. So Jack put all his money—we liked to say it was gold coins—into a big tin can and hid it among the stones of one of those walls out old Barnum Road. Not long after that, Jack was knocked off by rival gangsters and the location of his treasure died with him. We looked and we looked and we looked, but never found it. Still, the many happy days spent following those old walls and poking among the ruinous stones for a mobster’s loot remains a treasured memory.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on June 12, 2020