Casa Susanna

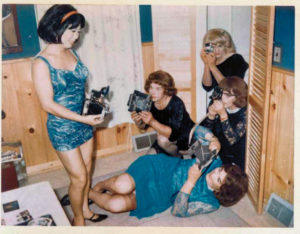

No historical marker stands in front of the ramshackle boardinghouse formerly known as Casa Susanna. Perhaps that’s for the best. After all, this is more a place of memory than a site of history. Whatever fame this venue has achieved in recent years is lodged for the most part in the imagination of those who have never set foot in the Catskill Mountains, who live elsewhere, far from the quiet road in the valley of the East Kill where Casa Susanna—now in moldering anonymity—still stands. Fifty years ago, Casa Susanna operated as a modest B&B, catering to an unusually glamorous clientele, as well as to the occasional plaided hunter who was happy to share the dinner table and a friendly game of Scrabble with his fellow guests. By all accounts, Casa Susanna was your typical getaway lodge, except for one little detail: the majority of the guests at this otherwise unexceptional hostelry were men who dressed in women’s clothing. The surviving photographs from the resort’s heyday suggest that lodgers at Casa Susanna enjoyed nothing so much as lounging around in their demure swing dresses, smoking cigarettes, sharing gossip, and trading make-up tips. It was only through happenstance that any of these photos did survive.

One day around the turn of the 21st century, a self-described “gentle punk rocker turned furniture dealer” by the name of Robert Swope was poking around in a Manhattan flea market. He came upon a large box brimming with miscellaneous photographs of strangers, “Instant Ancestors” as they are called in the antiques trade. He started rummaging through the box and soon exhumed a “small image of what was obviously a drag queen on an ugly sofa with plastic slipcovers happily knitting while dressed in conservative women’s daywear. I felt electrified.” He dug deeper into the box. Eventually he retrieved “about four hundred images: a hundred loose snapshots, both color and black-and-white, and three neatly preserved photo albums.” Swope knew he had found something special. For a pittance he purchased the entire lot. “What I discovered that day in New York was the personal photo collection, one might say ‘family albums,’ of Susanna, a professional female impersonator—as her business card glued to one of the album covers attested.” No other clue was found regarding the provenance of the remarkable cache of “photos documenting everyday women, going about their everyday lives—except that these women were men who probably lived as truck drivers, accountants, or bank presidents during the week.” In 2005, Swope and his partner, Michel Hurst, published 120 of the rescued photographs in a coffee table book under the title Casa Susanna. Apart from Swope’s brief introduction, the volume consists entirely of uncaptioned pictures of men dressed as women, images unfixed by any words of explanation. Thus they invite the reader to use imagination to fill in the gaps

Following the book’s publication, a fuller story of Casa Susanna began to emerge. Former guests have been coming forth with their accounts. Academic dissertations are being written on the subject. Casa Susanna is all over the internet. The history of the resort is becoming increasingly well-documented. For instance, we now know that Susanna—also known as Tito Valenti—and her wife, Marie, were the owners of the resort. They lived in the city but operated Casa Susanna on weekends and holidays. Tito was a professional journalist who worked for a Spanish-language radio station. Marie owned a wig shop patronized by the theater industry as well as the cross-dressing community. Most of the photographs rescued from the flea market were taken and developed by a videographer named Jack Malick, who, when going en femme, was known as Andrea Susan. Psychologists from the Kinsey Institute would occasionally drop in for a stay, just to check out what was going on. In his book A Year Among the Girls (1966), Darrell G. Raynor included a humorous account of a weekend spent there. Alas, all good things must come to a close. The resort never turned a profit. Toward the end of the sixties, Susanna decided she had had enough. She announced that she was going to live “full time as a woman.” Casa Susanna was shuttered, the property sold a couple years later, and Susanna herself disappeared into legend. No record of what became of her.

Following the book’s publication, a fuller story of Casa Susanna began to emerge. Former guests have been coming forth with their accounts. Academic dissertations are being written on the subject. Casa Susanna is all over the internet. The history of the resort is becoming increasingly well-documented. For instance, we now know that Susanna—also known as Tito Valenti—and her wife, Marie, were the owners of the resort. They lived in the city but operated Casa Susanna on weekends and holidays. Tito was a professional journalist who worked for a Spanish-language radio station. Marie owned a wig shop patronized by the theater industry as well as the cross-dressing community. Most of the photographs rescued from the flea market were taken and developed by a videographer named Jack Malick, who, when going en femme, was known as Andrea Susan. Psychologists from the Kinsey Institute would occasionally drop in for a stay, just to check out what was going on. In his book A Year Among the Girls (1966), Darrell G. Raynor included a humorous account of a weekend spent there. Alas, all good things must come to a close. The resort never turned a profit. Toward the end of the sixties, Susanna decided she had had enough. She announced that she was going to live “full time as a woman.” Casa Susanna was shuttered, the property sold a couple years later, and Susanna herself disappeared into legend. No record of what became of her.

What about the actual place on the ground that provided the setting, the backdrop, for so many of the now-famous pictures? Drive over there and you will immediately recognize the house from the photos made by the late Andrea Susan oh so many years ago: the same rambling Victorian boardinghouse, typical of so many others found on the Mountaintop. It’s still painted white, though in need of a fresh coat and a new roof. The bluestone walkway—visible in several of Andrea Susan’s photos—leading up to the front door and around the side of the house is obscured now by the accumulation of leaf litter and encroaching vegetation. The venerable maple that once bore a sign saying “Casa Susanna” is still there, but the sign itself is gone—the one that Susanna herself painted and nailed to the tree, because “This may be the only time I’ll ever get to see my name in big letters anywhere!” A few years ago, the property came on the market. The ad read: “You can own the actual Casa Susanna!”—but it failed to sell, even at a bargain price. Around that time, thieves got into the closed-up house and removed all the wiring and plumbing to sell for scrap. Large limbs stripped by wind from senescent spruces litter the yard. Like so many erstwhile family resorts, sleepaway camps, and Eisenhower-era theme parks around these mountains, Casa Susanna teeters on the edge of oblivion, slowly but surely collapsing into the old earth.

the photos made by the late Andrea Susan oh so many years ago: the same rambling Victorian boardinghouse, typical of so many others found on the Mountaintop. It’s still painted white, though in need of a fresh coat and a new roof. The bluestone walkway—visible in several of Andrea Susan’s photos—leading up to the front door and around the side of the house is obscured now by the accumulation of leaf litter and encroaching vegetation. The venerable maple that once bore a sign saying “Casa Susanna” is still there, but the sign itself is gone—the one that Susanna herself painted and nailed to the tree, because “This may be the only time I’ll ever get to see my name in big letters anywhere!” A few years ago, the property came on the market. The ad read: “You can own the actual Casa Susanna!”—but it failed to sell, even at a bargain price. Around that time, thieves got into the closed-up house and removed all the wiring and plumbing to sell for scrap. Large limbs stripped by wind from senescent spruces litter the yard. Like so many erstwhile family resorts, sleepaway camps, and Eisenhower-era theme parks around these mountains, Casa Susanna teeters on the edge of oblivion, slowly but surely collapsing into the old earth.

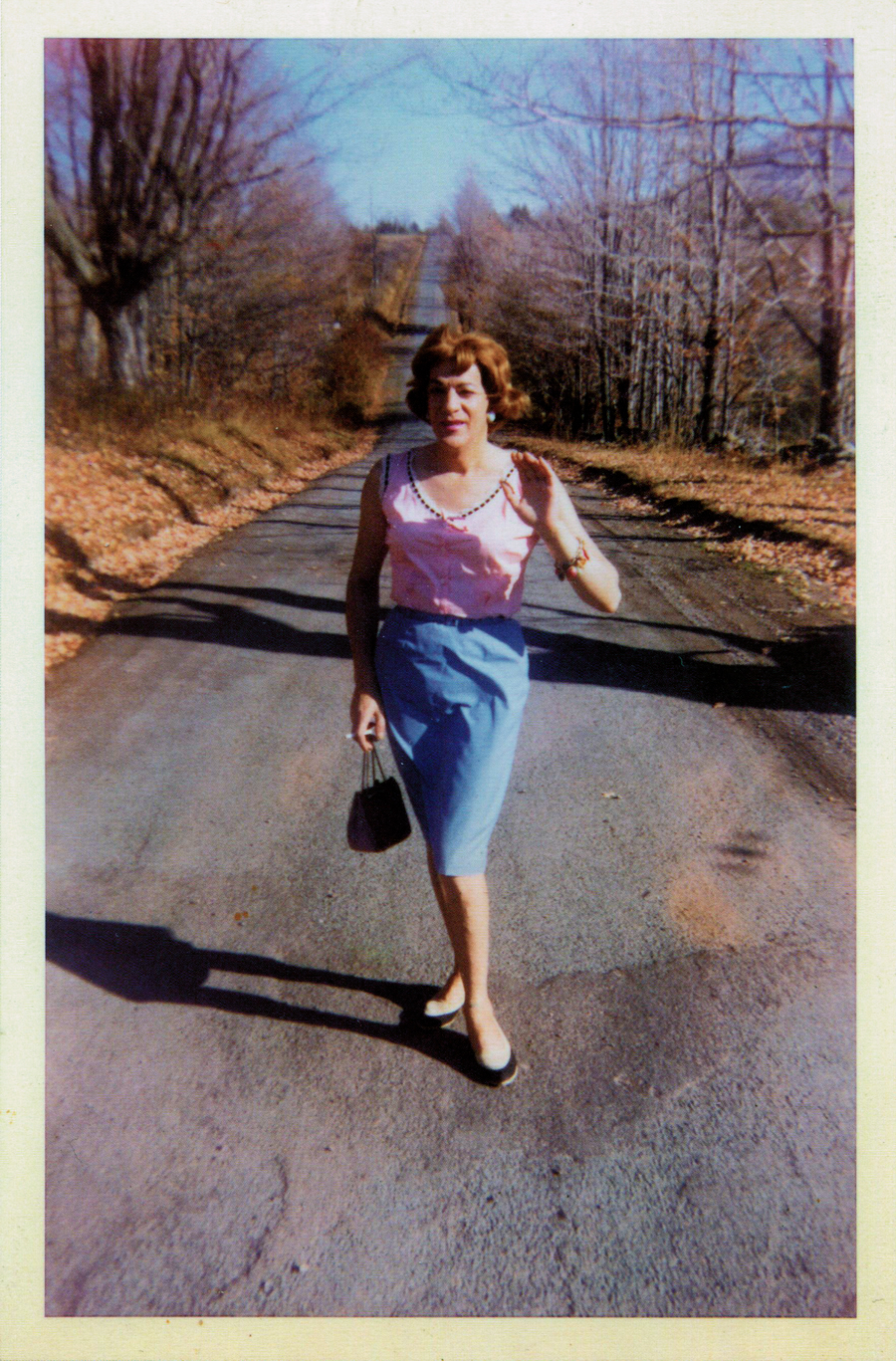

Most touching and indeed most haunting of all the Casa Susanna photos appears near the end of the book. It’s a color image taken on the road directly in front of Casa Susanna. No cars in sight. The trees seem recently shorn of their leaves. It’s probably near the end of October. Susanna is standing in the middle of the empty road. She is wearing a pale blue skirt, pink top, and comfortable shoes. A purse dangles from her right hand, cigarette between her fingers. She appears ready to depart somewhere. With her left hand she is waving directly to the camera. She is waving goodbye.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on May 18, 2018