Boot Jack Rock

A rock is just a rock until its secret is known—or as they used to say in olden times, until its guardian spirit is teased out. The ancient Romans had a term for it—genius loci—and this presiding spirit of place could manifest in any of innumerable natural forms, both organic and inorganic. One never knew when—or under what aspect—the spirit might come into view. It could be in the guise of a mountain, a flower, a river, a snake, a waterfall, a tree, or a even rock. Each human being, too, was thought to have an attendant “genius” or spirit, a belief that has survived to the present day under the name of “guardian angel.” For the Romans, to recognize the genius loci was to acknowledge the sacredness of a place. Sometimes they built shrines and temples to mark where the human and divine most readily mingled, those luminous grottoes where nymphs and satyrs and the occasional Olympian deity might cavort with the merely human. Over the course of their history, Americans generally have had little truck with pagan shenanigans, but some people still use the term genius loci, though in the diminished sense of referring to a location’s distinctive atmosphere. Gone is any suggestion of the otherworldly. Yet surely those who dwell here in the Land of Rip Van Winkle—and daily imbibe its “old air”—know that there is more to the genius loci of these mountain haunts than simply a fleeting mood of the ambient air.

Consider the craggy environs just south of the erstwhile Catskill Mountain House. There, if you follow one or another of the long-established trails leading up South Mountain, you pass a variety of geological installations that, back in the heyday of 19th century summer resorts, were known as “Sphinx,” “Druid Rocks,” and “Fairy Spring.” Names such as these were intended to put the casual Victorian hiker on alert for wayward sprites and goblins, much as today’s trailhead signage warns of ticks. Yet not everyone was willing to play along with this kind of vacation make-believe. As one jaded observer in 1877 put it: “The greatest object of interest to the ordinary summer tourist is some rock, mound, or tree bearing a fancied resemblance to something which it could not by any possibility be. . . . This strange preference bears some analogy to the zest which many persons have for puns, of which even the most trivial and disputable sort they hold in greater esteem than the finest philosophy, heartiest humor, profoundest research, and loftiest poesy. These chance physical resemblances are the unintentional puns of nature; they find profound admirers in all famous resorts.” To judge from the rhapsodic guidebooks of those bygone days, hardly an outcrop of sandstone or crack in the conglomerate wasn’t dubbed with a breezy epithet.

Consider the craggy environs just south of the erstwhile Catskill Mountain House. There, if you follow one or another of the long-established trails leading up South Mountain, you pass a variety of geological installations that, back in the heyday of 19th century summer resorts, were known as “Sphinx,” “Druid Rocks,” and “Fairy Spring.” Names such as these were intended to put the casual Victorian hiker on alert for wayward sprites and goblins, much as today’s trailhead signage warns of ticks. Yet not everyone was willing to play along with this kind of vacation make-believe. As one jaded observer in 1877 put it: “The greatest object of interest to the ordinary summer tourist is some rock, mound, or tree bearing a fancied resemblance to something which it could not by any possibility be. . . . This strange preference bears some analogy to the zest which many persons have for puns, of which even the most trivial and disputable sort they hold in greater esteem than the finest philosophy, heartiest humor, profoundest research, and loftiest poesy. These chance physical resemblances are the unintentional puns of nature; they find profound admirers in all famous resorts.” To judge from the rhapsodic guidebooks of those bygone days, hardly an outcrop of sandstone or crack in the conglomerate wasn’t dubbed with a breezy epithet.

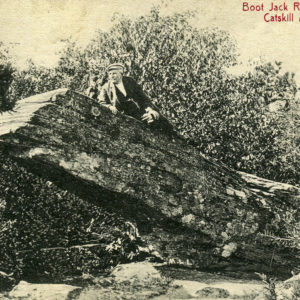

Remarkable then to realize that one of the more eye-catching of the lithic curiosities on South Mountain is never mentioned in the vast annals of 19th century Catskills boosterism. Were it not for an early 20th century postcard published by one C.O. Bickelmann of Tannersville, this particular rock—a striking glacial erratic inclined at an angle as if pointing at some prodigy on the now-occluded ceiling of heaven—might well have remained nameless, if not limned. Depicted on the postcard is the prodigious slab of sandstone in all its glory. Lounging vigorously across its upper surface is a middle-age man who bears an uncanny resemblance to Captain Kangaroo. He seems to be taking in a view. The surrounding forest is young and scruffy. The scene is sun-drenched, in stark contrast to the shade-bound depths of mature forest that harbors the site today. Emblazoned in Devonian red across the upper right corner of the old postcard are the words: “Boot Jack Rock, South Mt., Catskill Mts., N.Y.” A name, they say, is knowing, though comparatively few in our fashionable times will know what a boot jack is.

They also say that a picture is worth a thousand words—especially if it comes from the hand of a preeminent artist. Thomas Cole (1802-1848) made his first visit to the precincts of South Mountain during the fall of 1825. He returned there regularly for the rest of his life, exploring every nook and cranny of this most famous stretch of the Catskill escarpment. At some point in the 1830s, Cole sketched a particular no-name rock that, seventy years later, would be displayed on a picture postcard and labeled Boot Jack. A certain agitation—or is it urgency?—characterizes the lines in Cole’s sketch, as if the artist had to work quickly to capture a protean something that did not wish to be captured. The rock itself is immediately recognizable as the one in the Bickelmann postcard, but the artist’s sketch includes a more disquieting element. In the foreground is the whispery outline of a human-shaped figure, a phantom presence barely discernible, as if it were some weird shadow cast by the boulder, or a faint essence having just emerged from it.

Another artist who spent time sketching around South Mountain was Cole’s illustrious student, Frederic Church (1826-1900). Cole introduced him to the rock. The young man immediately got the picture of what was going on here. A few years later, in 1847, he incorporated the rock’s singular profile into one of his more “imaginative” early works, a large painting titled Christian on the Borders of the Valley of the Shadow of Death, Pilgrim’s Progress. It hangs today on a wall in the studio at Olana, the artist’s home in Hudson, now a state historic site. The subject of Church’s painting is drawn from an episode in Pilgrim’s Progress, John Bunyan’s bestselling allegorical tale, first published in 1678 but still quite popular in Church’s day, especially in his native New England. Church portrays the story’s main character, a fellow named Christian, who at this point in his adventure is dressed in battle armor and looking back over a dark and wild terrain of horrors he has just traversed. In the middle distance, an ominous mushroom cloud can be seen spewing heavenward from a blazing volcanic cauldron. As described by Bunyan: “Now, morning being come, he looked back; not out of desire to return, but to see by the light of the day, what hazards he had gone through in the dark. . . . Also now he saw the hobgoblins, and satyrs, and dragons of the pit; but all afar off, for after break of day they came not nigh. Yet they were discovered to him according to that which is written, ‘He discovers deep things out of darkness and brings out to light the shadow of death’.” Church’s rendition of the scene is framed by a blasted tree on the left and an imposing cliff on the right. Toward the lower right corner of the picture, at the base of the cliff amid a jumble of other boulders, is the unmistakable form of the same rock sketched by Cole in the previous decade. Church, like his mentor before him, has teased out an inherent presence in this place ordinarily overlooked, or perhaps conveniently forgotten.

To return then to Bickelmann’s postcard. At first glance, nothing in this old photo of a nameless rock adorned with a silly name seems unsettling. But after one spends a little while with the images by Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, other possibilities begin to emerge. Look more closely at that fellow draped across the top of the rock. Look how he is looking at something just out of the frame. Who or what does he see? Near or far? Who or what sees him? And what of us, we who gaze upon this image, or any image: Who or what do we see? Near or far? Who or what sees us? The nameless, too, is knowing.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on July 12, 2019