Austin’s Glen

In one of his books on the subject of Catskill Mountain geology, the venerable George H. Chadwick paused to reflect on this place he considered his home territory: “To all of us collaborators the region, old and much visited as it is, has furnished surprises in the way of fresh discovery.” He wrote these words in 1944. They still ring true.

Consider the students of geology. Today they can be seen gathered along the side of the highway. Each of them is wearing a high-visibility safety vest. Each is holding a brand new clipboard. Each has a pen in hand. They are listening to their teacher as he tells them what is going on around here. It’s been going on for a very long time. The students’ attention is directed to what lies right in front of them.

Each has a pen in hand. They are listening to their teacher as he tells them what is going on around here. It’s been going on for a very long time. The students’ attention is directed to what lies right in front of them.

They are standing at the base of a hundred-foot escarpment. They see multiple contorted layers of limestone and shale, sandstone and chert. They are told that this is a complicated sedimentary lithology. It was exposed fifty years ago, the result of highway construction. The students are looking at the north side of a deep roadcut. They have been handed a diagram depicting the structural complexities of the exposure, each layer of rock designated with its appropriate geological denomination. As pointed out by the teacher, the strike line of the bedrock proceeds south, across the excavated interval with its four lanes of traffic, to the opposite side of the roadcut. Over there is another prominent escarpment. Even cursory inspection reveals that something is off here. The exposure on the south side presents a dramatic contrast in structural geometry compared to that on the north. The bedrock layers on the two sides of the roadcut do not match up. What could explain so profound a difference in chthonic architecture over so short a distance?

There’s no telling, at least not directly. Whatever material traces there were of those long-past geological events got obliterated during the construction project. On the other hand, no story at all would have been available today had the road cut not been made. The entire sequence of rock—stretching from the late Ordovician Period through the lower Middle Devonian—would have remained hidden in the bowels of the earth. Sure, that missing interval of layered bedrock—spanning roughly 50 million years—might have proven a geologist’s treasure trove. Yet all hope is not lost! Something can still be inferred from what abides. The exposures that stand tell a story—the story of the earth itself, at least so far as it’s expressed in this particular place along Route 23 in Leeds, New York. The telling of that story, however, is best left to the geology teacher.

It’s another story I want to tell here. It takes place not far from where the geology students are gathered, down along Catskill Creek in the steep-walled gorge known as Austin’s Glen. It concerns the family of the artist Ralph Albert Blakelock—sometimes referred to as the “Great Mad Genius.” Just how “mad” he actually was is a subject for debate, but certainly he had his problems. Enough of them that in 1899, at age 52, he was put away in psychiatric hospitals for the next seventeen years, leaving his wife, Cora, to fend for herself and their eight children. Unable to afford the city, she made her way to Leeds. “By the time Cora and her children moved into the area,” a biographer reports, “the town was a shadow of its former self.” The wealthy who used to frequent the town on their way to the Catskill Mountain House, “had long since fled to Saratoga and been supplanted by New York City’s lower middle class, who had started to arrive when the railroad was built.” Even so, Cora still found it difficult to pay the family bills.

It’s another story I want to tell here. It takes place not far from where the geology students are gathered, down along Catskill Creek in the steep-walled gorge known as Austin’s Glen. It concerns the family of the artist Ralph Albert Blakelock—sometimes referred to as the “Great Mad Genius.” Just how “mad” he actually was is a subject for debate, but certainly he had his problems. Enough of them that in 1899, at age 52, he was put away in psychiatric hospitals for the next seventeen years, leaving his wife, Cora, to fend for herself and their eight children. Unable to afford the city, she made her way to Leeds. “By the time Cora and her children moved into the area,” a biographer reports, “the town was a shadow of its former self.” The wealthy who used to frequent the town on their way to the Catskill Mountain House, “had long since fled to Saratoga and been supplanted by New York City’s lower middle class, who had started to arrive when the railroad was built.” Even so, Cora still found it difficult to pay the family bills.

She and her unmarried children wound up in Austin’s Glen, living in a dilapidated house in the shadow of an abandoned mill. Soon after that, Cora’s oldest son, Carl, his wife, and their children moved into a ramshackle house close by in the glen. Another of Blakelock’s biographers describes the setting: “Neither of the houses had running water, electricity, a telephone, or central heating. Drinking water had to be carried in pails from a spring under the cliff in back of the house, a spring that was often frozen in the winter. Also, the family collected rainwater from the roof in a barrel and melted snow on the stove for washing. They used railroad ties taken from an abandoned cog railroad for heating and cooking in the fireplace.”

The eldest of Carl’s children was a boy named Eden. He enjoyed exploring the woods and cliffs of his new neighborhood. He liked to play in the ruins of the mill. He spent a lot of time there. He was a good swimmer and saved many hapless bathers from drowning in the swift-flowing waters of the creek. As he grew older, he assisted in his father’s sign-painting business. He also inherited his grandfather’s artistic talents, which he discovered by accident one summer afternoon when—just for fun—he tried his hand at landscape painting. He had never known his grandfather, and the only examples he had seen of the famous painter’s work were one small painting and some sketches his grandmother kept in her house. “The young man does not paint from life,” a newspaper reporter wrote in 1931, “but portrays on canvas the images which come into his mind.” For a young man who had spent most of his life dwelling in the wild and nonconforming recesses of Austin’s Glen—and given his family background (his aunt Marian likewise was an extraordinary “instinctual” artist)—the manifestation of profound painterly talent is no surprise. Over the course of his long life, Eden Blakelock continued to paint landscapes just for fun—occasionally presenting his work in shows—but he did not pursue a career in art. Instead he became one of Catskill’s most prominent citizens, living into his early nineties. He is buried in the Jefferson Rural Cemetery in Catskill, on the heights just above Austin’s Glen.

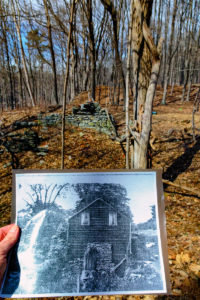

A few of us recently made a pilgrimage to Austin’s Glen to see if any remnants could be found of the Blakelock family’s time there. Although the glen is by no means remote—it is spanned by both Route 23 and the New York State Thruway—it feels remarkably far removed from the blooming, buzzing confusion of the second decade of the twenty-first century. Some of the oldest rocks in the region are found in this vicinity. Adjacent to the banks of Catskill Creek, the long-abandoned bed of the Catskill Mountain Railway is still traversable by foot, though with the passing of each storm such as Irene, more and more of it is washing away. Of the houses where the Blakelocks lived, only the foundation and fireplace stones remain. Sizable trees rise from the cellar holes. Metal sheathing from the roofs lies scattered about. No sign of the spring is to be found. The place today bears little resemblance to what is seen in the few old photos of it that survive.

After snapping some documentary pictures of the site, we investigated the remnants of the old mill and its dam. Same story: little left but foundation stones. It was a melancholy scene. But melancholy soon gave way to surprise, when we spotted a weathered inscription carved into a large boulder extending into the creek. It consisted of just two letters—“E.B.”—and a date, “1918.” Could it be that these were the initials of a fifteen year old boy named Eden Blakelock, a budding artist who, at this very spot, made his mark not in but on the world, a modest legacy written in stone? Of course, there’s no telling, at least not directly. Yet surely something might be inferred.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on March 30, 2018