Art Trail

Here in the Land of Rip Van Winkle, an art trail begins or ends at everybody’s front door. Innumerable are such trails, and infinite the vistas. After all, to live in this place is to dwell in a Hudson River School painting. Or so they say. Of course, there’s an official Hudson River School Art Trail blazed across the landscape. It’s a collaborative project of the Thomas Cole National Historic Site and other organizations, intended to bring visitors to the very places that inspired all those artists back in the day. The trail was opened in 2005 and today has 20 authorized stops, all of which are posted with edifying interpretive signage and supplemented by an online guide accessible anywhere via mobile device. “Wear comfortable shoes,” is the advice, “open your eyes and prepare to be inspired.”

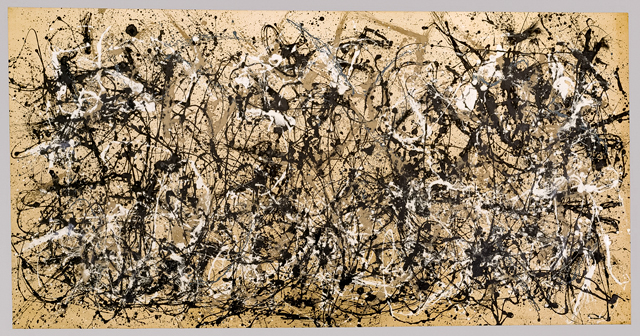

In the Catskill Mountains, no month is more inspiring than October. Some days are like a Thomas Cole picture, others more like a Jackson Pollock “action painting.” One time—it was a few years back—I enjoyed a Frederic Church kind of day. I had an appointment at Olana, that great big house on the hill across the river from the village of Catskill. I had been invited there to talk with some high school students about the “sublime” and the importance of this idea to mid-nineteenth century American artists. The art trail that leads from my house to Olana is paved, so I was able to drive there. This gave me opportunity to compose a few thoughts along the way on the sublime.

Nowadays we tend to use that word interchangeably with “beautiful” or “awesome.” But in the heyday of the Hudson River School, the term sublime had a very specific meaning. Thomas Cole and Frederic Church—as well as the collectors who bought their paintings—understood the sublime to be that feeling experienced in the face of natural phenomena that astonish, overwhelm, or terrify us: thundering waterfalls, erupting volcanoes, hurricanes, forest fires, earthquakes, and tempestuous seas. All such phenomena become “delightful,” according to the philosopher Edmund Burke, “when we have an idea of pain and danger, without being actually in such circumstances.” In the current lingo, one might say that the sublime is imminent peril well curated. Cole, Church, and other artists among the Hudson River School sought to evoke this experience in the viewers of their paintings. Some might consider this to be the landscape equivalent of secondary smoke. And indeed, this is about as close to nature as many connoisseurs of the sublime care—or dare—to get. But it should be kept in mind that if a sublime situation is overly curated—that is, made so safe as to eliminate any sense of danger—the whole business is reduced to something “picturesque.” The recently installed fencing and observation platform at Kaaterskill Falls is a case in point: no more harrowing selfies on the lip of the falls. Henceforth we will all take the same pretty picture from the safety of a well-built paddock with a sanctioned view.

Nowadays we tend to use that word interchangeably with “beautiful” or “awesome.” But in the heyday of the Hudson River School, the term sublime had a very specific meaning. Thomas Cole and Frederic Church—as well as the collectors who bought their paintings—understood the sublime to be that feeling experienced in the face of natural phenomena that astonish, overwhelm, or terrify us: thundering waterfalls, erupting volcanoes, hurricanes, forest fires, earthquakes, and tempestuous seas. All such phenomena become “delightful,” according to the philosopher Edmund Burke, “when we have an idea of pain and danger, without being actually in such circumstances.” In the current lingo, one might say that the sublime is imminent peril well curated. Cole, Church, and other artists among the Hudson River School sought to evoke this experience in the viewers of their paintings. Some might consider this to be the landscape equivalent of secondary smoke. And indeed, this is about as close to nature as many connoisseurs of the sublime care—or dare—to get. But it should be kept in mind that if a sublime situation is overly curated—that is, made so safe as to eliminate any sense of danger—the whole business is reduced to something “picturesque.” The recently installed fencing and observation platform at Kaaterskill Falls is a case in point: no more harrowing selfies on the lip of the falls. Henceforth we will all take the same pretty picture from the safety of a well-built paddock with a sanctioned view.

Back to that October morning. I was about halfway to Olana when I came upon one of those dreaded Day-Glo highway signs warning of upcoming hazard. In this case it was “Reduce Speed, Work Zone Ahead, Fines Doubled.” Traffic on the art trail came nearly to a standstill, even though time continued to pass at a sluggish rate. After what seemed an eternity, I drew near a place where men and women were laboring away, repaving a forlorn stretch of the art trail. A little late in the season for this kind of work, it seemed to me. The morning was blustery and cold. Thick and noisome vapors were rising from freshly laid tar, enveloping the workers and their equipment—not to mention all innocent passersby—in an appalling mephitis. The morning light now extinguished, this dreary scene brought to mind a crepuscular line of verse: “Darkening the day-time torch-like with the smoking blueness of Pluto’s gloom.” The next couple miles of the art trail were far removed from any pretty Hudson River School picture. Instead, it was more like a dreadful creep through a failed installation piece, an abominable aesthetic hybrid between a night ride down the Jersey Turnpike and a Robert Smithson glue pour. Close by the fuming art trail was a fetid-looking lake encircled by dead trees. A deer carcass lay in the breakdown lane. An old man was pedaling a wobbly bicycle against the traffic, careening among the slow-moving vehicles. Next up, a billboard became visible through the pall of baleful emanations—an ad for something called WatchTVEverywhere.com. Under these conditions, it was the only feature in the landscape that made any sense. I wanted to stop and take a moody photograph, but this was no place for art. I had to keep my eye on the road.

Back to that October morning. I was about halfway to Olana when I came upon one of those dreaded Day-Glo highway signs warning of upcoming hazard. In this case it was “Reduce Speed, Work Zone Ahead, Fines Doubled.” Traffic on the art trail came nearly to a standstill, even though time continued to pass at a sluggish rate. After what seemed an eternity, I drew near a place where men and women were laboring away, repaving a forlorn stretch of the art trail. A little late in the season for this kind of work, it seemed to me. The morning was blustery and cold. Thick and noisome vapors were rising from freshly laid tar, enveloping the workers and their equipment—not to mention all innocent passersby—in an appalling mephitis. The morning light now extinguished, this dreary scene brought to mind a crepuscular line of verse: “Darkening the day-time torch-like with the smoking blueness of Pluto’s gloom.” The next couple miles of the art trail were far removed from any pretty Hudson River School picture. Instead, it was more like a dreadful creep through a failed installation piece, an abominable aesthetic hybrid between a night ride down the Jersey Turnpike and a Robert Smithson glue pour. Close by the fuming art trail was a fetid-looking lake encircled by dead trees. A deer carcass lay in the breakdown lane. An old man was pedaling a wobbly bicycle against the traffic, careening among the slow-moving vehicles. Next up, a billboard became visible through the pall of baleful emanations—an ad for something called WatchTVEverywhere.com. Under these conditions, it was the only feature in the landscape that made any sense. I wanted to stop and take a moody photograph, but this was no place for art. I had to keep my eye on the road.

Ultimately, the gloom gave way and I made it through. It was like driving out of Plato’s Cave. The early morning sun was shining. Traffic again began to flow. I was back inside a Hudson River School painting! Soon enough, Olana came into view on the far side of the Hudson River, perched gloriously atop its long hill, saturated in smoldering claret light. After that toxic interlude along the art trail, my lungs were aching, but that too would pass. I was ready to talk about the sublime.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on October 26, 2018