Apple Blossom Time

Now is when they come into their brief visibility, the fragrant ghosts of May. They hover along the periphery of mountain roads and in the thick of second-growth forests where once the orchards grew. Their names—all but forgotten today—sound like poems: Gloria Mundi, Seek-No-Further, June-Eating, Summer Queen, Esopus Spitzenburg, Ox Noble, Scrivener’s Red, Winesap, Graniwinkle, and Yellow Everlasting. These relic apple trees, their heyday long-past, now stand ragged and isolate throughout the Catskill Mountains. Nevertheless, they continue to put forth their blooms.

Malus pumila, the familiar apple tree: like so many of us, it is an Old World species. Historians reckon that Jamestown was where apples were first planted in America. That was in the year 1607 . Not long after that, orchards were established in the colonies at Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Meanwhile, the French were planting apples in Québec. The Eastern Woodland Indians knew a good thing when they saw it. Soon enough they were planting orchards of their own, far removed—at least at first—from the European settlers who provided them with seeds. In 1779, acting upon orders from George Washington, General John Sullivan led an expeditionary force of several thousand men across the Finger Lakes region to conduct a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois, who were allied with the British. When Sullivan’s expedition reached the Indian villages along Seneca Lake, they reported finding several well-established apple orchards—estimated to be nearly a hundred years old—which they promptly cut down and burned. A story used to be told out Oswego way of an orchard sold by Indians to white settlers around the year 1800. The trees were thirty or forty years old at the time and excellent producers. For a number of years after the transaction, the Indians returned in the autumn and gathered up the apples and carried them away. Each time this happened, the new owner would chastise them. The Indians always replied: “We sold the land but not the apples.”

. Not long after that, orchards were established in the colonies at Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Meanwhile, the French were planting apples in Québec. The Eastern Woodland Indians knew a good thing when they saw it. Soon enough they were planting orchards of their own, far removed—at least at first—from the European settlers who provided them with seeds. In 1779, acting upon orders from George Washington, General John Sullivan led an expeditionary force of several thousand men across the Finger Lakes region to conduct a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois, who were allied with the British. When Sullivan’s expedition reached the Indian villages along Seneca Lake, they reported finding several well-established apple orchards—estimated to be nearly a hundred years old—which they promptly cut down and burned. A story used to be told out Oswego way of an orchard sold by Indians to white settlers around the year 1800. The trees were thirty or forty years old at the time and excellent producers. For a number of years after the transaction, the Indians returned in the autumn and gathered up the apples and carried them away. Each time this happened, the new owner would chastise them. The Indians always replied: “We sold the land but not the apples.”

Over the course of the 19th century, apple cultivation was conducted in an increasingly scientific manner. This period is referred to as the golden age of American pomology. By the turn of the 20th century, Americans had produced nearly 14,000 distinct varieties of Malus pumila. Who knows but another 14,000 might have come into existence over the next century had not improvements in transportation and pressures of the marketplace put the brakes on all that. A quick look around the produce section in an American supermarket of the 21st century reveals a drastically diminished array of apple variety, a dozen or so if you’re lucky—Gala, Delicious, Fuji, Honeycrisp—and the same ones keep turning up wherever you go, from the Hannaford in Bangor to the Vons in San Diego. Many of these apples are imported from Chile and New Zealand. Observed one wry prophet in the 1904 U.S. Department of Agriculture Yearbook: “One of the weaknesses of consumers is an admiration for foods that are polished or have a gloss, and this nickel-plate fancy plays some queer pranks with foods.”

The internet informs us: “If you want apples, you have to shake the trees.” Sure, but first you have the plant the right trees. A few years ago, I started a small backyard apple orchard on our modest patch of ground in the Catskills Mountains, where a hundred years ago a small orchard used to thrive. A few of those venerable trees remain standing, but they have been neglected longer than I’ve been alive. Previously many more were scattered across the field, but over the course of my lifetime I have watched them fall, one by one, as the recovering forest edged in ever closer on them. In recent years I’ve been cutting back the trees, throwing more sunlight on the situation, which is how apples prefer it. The new orchard consists of six “heirloom” varieties—two each of King David, Campfield, and Harrison, all of which were purchased online from a nursery in Paso Robles, California, and shipped to the Land of Rip Van Winkle. Apparently there is some debate among professional apple growers as to what exactly the term “heirloom” means when applied to a cultivar, but for me an heirloom is simply an apple lineage with a story.

The internet informs us: “If you want apples, you have to shake the trees.” Sure, but first you have the plant the right trees. A few years ago, I started a small backyard apple orchard on our modest patch of ground in the Catskills Mountains, where a hundred years ago a small orchard used to thrive. A few of those venerable trees remain standing, but they have been neglected longer than I’ve been alive. Previously many more were scattered across the field, but over the course of my lifetime I have watched them fall, one by one, as the recovering forest edged in ever closer on them. In recent years I’ve been cutting back the trees, throwing more sunlight on the situation, which is how apples prefer it. The new orchard consists of six “heirloom” varieties—two each of King David, Campfield, and Harrison, all of which were purchased online from a nursery in Paso Robles, California, and shipped to the Land of Rip Van Winkle. Apparently there is some debate among professional apple growers as to what exactly the term “heirloom” means when applied to a cultivar, but for me an heirloom is simply an apple lineage with a story.

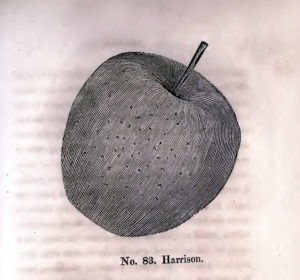

Consider the Harrison apple. As described in 1817 by the pioneer pomologist William Coxe, Esq.: “This is the most celebrated of the cider apples of Newark in New-Jersey: it is cultivated in high perfection, and to a great extent in that neighbourhood, particularly on the Orange mountain,” a place today more commonly known as the Watchung Mountains. Coxe informs us that the Harrison apple’s “shape is rather long, and pointed towards the crown—the stalk long; hence often called the long stem—the ends are deeply hollowed; the skin is yellow, with many black spots, which gives a roughness to the touch: the flesh is rich, yellow, firm and tough; the taste pleasant and sprightly, but rather dry—it produces a high coloured, rich, and sweet cider of great strength, commanding a high price in New York.” A prime beverage was made from the juice of Harrison apples by mixing it with a little Campfield. They called it “Newark Champagne.” It was all the rage for the first half of the nineteenth century, but later its popularity suffered a steep decline and urbanization claimed a large chunk of the former orchards. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Harrison apple was no longer being cultivated by commercial growers. In mid-century it was presumed extinct.

Newark in New-Jersey: it is cultivated in high perfection, and to a great extent in that neighbourhood, particularly on the Orange mountain,” a place today more commonly known as the Watchung Mountains. Coxe informs us that the Harrison apple’s “shape is rather long, and pointed towards the crown—the stalk long; hence often called the long stem—the ends are deeply hollowed; the skin is yellow, with many black spots, which gives a roughness to the touch: the flesh is rich, yellow, firm and tough; the taste pleasant and sprightly, but rather dry—it produces a high coloured, rich, and sweet cider of great strength, commanding a high price in New York.” A prime beverage was made from the juice of Harrison apples by mixing it with a little Campfield. They called it “Newark Champagne.” It was all the rage for the first half of the nineteenth century, but later its popularity suffered a steep decline and urbanization claimed a large chunk of the former orchards. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Harrison apple was no longer being cultivated by commercial growers. In mid-century it was presumed extinct.

But then in the Bicentennial year, along came a fruit collector from Vermont named Paul Gidez, who discovered a single, large Harrison apple tree on the grounds of an old cider mill in Livingston, New Jersey. Lucky for him he took several cuttings from that tree because shortly after his visit it was cut down to make room for a garden. Some years after that, the property was sold to a developer, who put up a bunch of condos. He also promised to install a plaque that would note the history of the cider mill, but in the end this will do little to distinguish the site from anyplace else in New Jersey. These days, whatever spirits return to the original haunts of the Harrison apple are likely not very fragrant. But thanks to the efforts of Mr. Gidez and others, the Harrison apple survives, here and there, including those recently planted in a tiny orchard somewhere in the Catskill Mountains.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on May 25, 2018