A Tale of Two Lean-tos

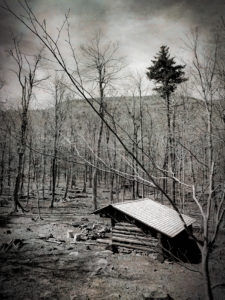

The old lean-to. For more than fifty years it stood, alongside the trail, near the headwaters of the Batavia Kill, providing shelter to innumerable backcountry travelers. In recent years it had been showing its age. Rotting floorboards, a leaking roof, and an irremediable odor of mustiness led one critic to comment: “A lean-to so embarrassing that even the local porcupines are ashamed to be seen here.” The authorities concluded it was time to do something about the situation. In spring of 2017, they sent a call out for volunteers: “Help build the new Batavia Kill lean-to!” And so, over the course of a week in June, a new structure was erected on a site 75 yards away from the old lean-to—in a relatively untrammeled, sylvan recess of mixed hardwoods and birdsong. There in the full flush of early summer, no one on the project noticed the signs indicating that the flat upon which they were building was, in fact, an ephemeral wetland. Although relatively dry at that moment, for a good month or so each spring the new lean-to would be abutting a murky swamp.

On the last day of April 2018, I hiked up the Batavia Kill Trail from the end of Big Hollow Road. I wondered how the new lean-to had fared over the course of its first winter. On the way I stopped by to inspect the site of the old lean-to. It was razed last October. “Out with the old, in with the new!” was the rallying cry used by the authorities to muster some unpaid help to aid in the tearing down. “Volunteers will dismantle the shelter, and properly dispose of the materials. Our work will allow soil and vegetation to recover, and will direct use toward the new site.” The project—referred to as “lean-to decommissioning”—took a couple days, which was a bit longer than it took authorities a half century ago to “decommission” the famed Catskill Mountain House and Laurel House, but still pretty quick for this kind of work. The old lean-to and its attendant outhouse were demolished, the stones of the fire ring scattered, and remnant scraps of wood burned. Lastly, formidable “No Camping” signage was installed on surrounding trees. Then a long winter set in. Only recently has it loosened its grip. Now on this first warm day of spring, the site presented a most dreary scene. Instead of the welcoming albeit frowzy shelter of old, I alighted upon a blackened, trampled, forlorn patch of ground that makes the potter’s field seem a merry place. Even the weeds were reluctant to take root here. Whatever recovery might take place was yet in the offing.

to inspect the site of the old lean-to. It was razed last October. “Out with the old, in with the new!” was the rallying cry used by the authorities to muster some unpaid help to aid in the tearing down. “Volunteers will dismantle the shelter, and properly dispose of the materials. Our work will allow soil and vegetation to recover, and will direct use toward the new site.” The project—referred to as “lean-to decommissioning”—took a couple days, which was a bit longer than it took authorities a half century ago to “decommission” the famed Catskill Mountain House and Laurel House, but still pretty quick for this kind of work. The old lean-to and its attendant outhouse were demolished, the stones of the fire ring scattered, and remnant scraps of wood burned. Lastly, formidable “No Camping” signage was installed on surrounding trees. Then a long winter set in. Only recently has it loosened its grip. Now on this first warm day of spring, the site presented a most dreary scene. Instead of the welcoming albeit frowzy shelter of old, I alighted upon a blackened, trampled, forlorn patch of ground that makes the potter’s field seem a merry place. Even the weeds were reluctant to take root here. Whatever recovery might take place was yet in the offing.

I proceeded up the trail to the turnoff for the new lean-to. The scene here was even more dismal than the one I had just vacated. Between where I stood and the new lean-to—visible through the bedraggled trees spared from the chainsaw—stretched an inky abyss of shallowness. Along the edge of this Lethean slackwater, the muddy ground was littered with plastic wrappers, sodden cardboard, unspeakably grimy undergarments, and a wad of soiled toilet paper. Close by the lean-to was a midden of tawny macaroni and cheese not yet discovered by a bear. I arrived at the shelter to find it unoccupied, or perhaps abandoned is a better word. The inside of the log structure had already acquired that distinctive funk that goes with all lean-tos—a regrettable amalgam of old woodsmoke and fermenting laundry.

I proceeded up the trail to the turnoff for the new lean-to. The scene here was even more dismal than the one I had just vacated. Between where I stood and the new lean-to—visible through the bedraggled trees spared from the chainsaw—stretched an inky abyss of shallowness. Along the edge of this Lethean slackwater, the muddy ground was littered with plastic wrappers, sodden cardboard, unspeakably grimy undergarments, and a wad of soiled toilet paper. Close by the lean-to was a midden of tawny macaroni and cheese not yet discovered by a bear. I arrived at the shelter to find it unoccupied, or perhaps abandoned is a better word. The inside of the log structure had already acquired that distinctive funk that goes with all lean-tos—a regrettable amalgam of old woodsmoke and fermenting laundry.

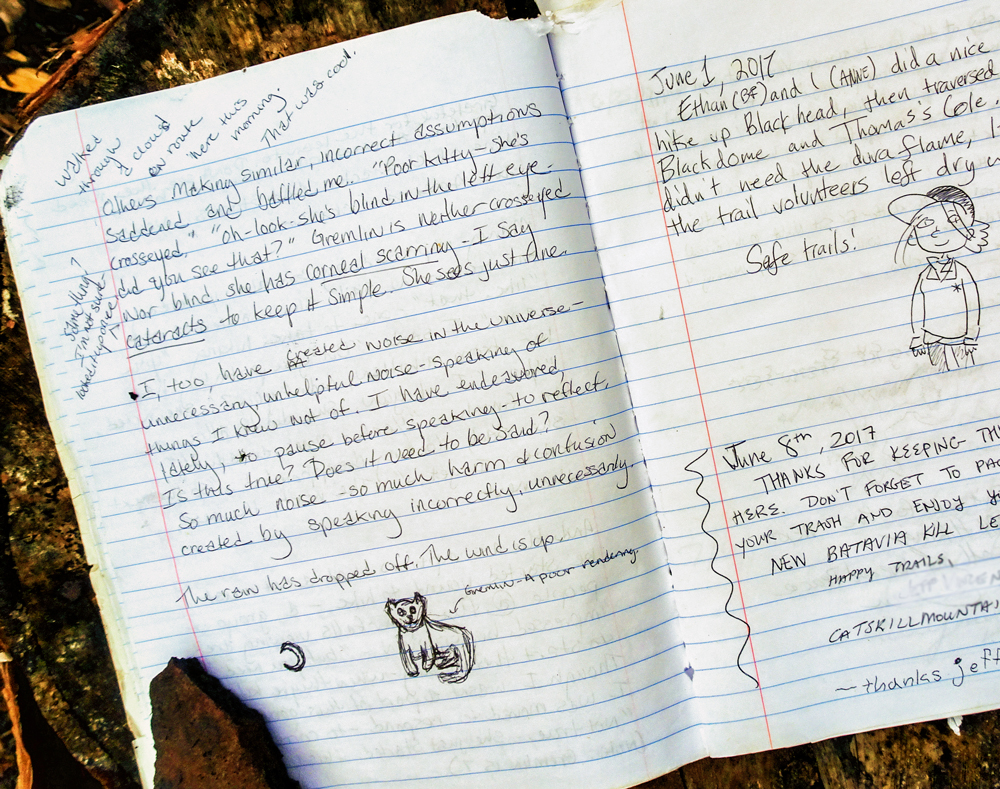

I took a quick look around in hope of finding something of interest. I was in luck. Tucked away on a high, dark shelf was a ragged notebook—the lean-to’s register. It had been transferred here from the old lean-to. Inscribed on its mouse-eaten pages were the usual mundane reports of trail conditions, mountain heroics, and praises to various divinities, but toward the end the volume I came upon a delightful, extended entry written by a young woman who hikes with her cat. She—or rather they—were among of the last visitors to the old lean-to before it was taken down. Alas, the author did not identify herself, but she does tell us the name of her feline companion: Gremlin.

The author offers a loving account of how she and Gremlin wound up at the old Batavia Kill lean-to on a soggy Monday morning in May. Two days earlier “they” had conceived and planned their hike in the Guilderland Starbucks. “Guilderland,” she writes, “what a name for a town.” They stopped first to see Kaaterskill Falls, crowded with visitors, then proceeded to the trailhead on Peck Road in Maplecrest. That night they got caught out in the rain while sleeping on a ledge at Acra Point. Now they were here at the old lean-to, drying out and waiting for a break in the weather. After recounting their adventures along the trail, the author pauses her story to observe: “Grateful for the lean-to. Don’t see the need for a new one. This one has tons of character and stories. New—an American obsession.”

earlier “they” had conceived and planned their hike in the Guilderland Starbucks. “Guilderland,” she writes, “what a name for a town.” They stopped first to see Kaaterskill Falls, crowded with visitors, then proceeded to the trailhead on Peck Road in Maplecrest. That night they got caught out in the rain while sleeping on a ledge at Acra Point. Now they were here at the old lean-to, drying out and waiting for a break in the weather. After recounting their adventures along the trail, the author pauses her story to observe: “Grateful for the lean-to. Don’t see the need for a new one. This one has tons of character and stories. New—an American obsession.”

The account returns to her experience the previous day at the crowded waterfall. “Many impressed by Gremlin yesterday; one woman said she wanted a cat ‘like that’—one to take hiking. ‘You can,’ I said. ‘But you probably had her from a kitten, didn’t you?’ she noted. ‘Yes,’ I began. She didn’t let me finish. ‘Yeah—mine’s an adult,’ she said, looking disappointed. ‘So the next kitten I get—.’ The next, the next, the next.” The author continues, telling how she overheard a group of people at the upper falls viewing platform talking between themselves about Gremlin. Someone said, “You need to start them young—when they’re kittens.” The author was moved to interject: “Not true. She just started this year,” adding: “Gremlin is 7.” She laments how people are always making “similar, incorrect assumptions” about Gremlin: “‘Poor kitty—she’s cross-eyed.’ ‘Oh look, she’s blind in the left eye.’ Gremlin is neither cross-eyed nor blind. She has corneal scarring—I say cataracts to keep it simple. She sees just fine.” The author confesses that all these ill-informed comments about Gremlin sadden and baffle her. On a wistful note she resumes: “I, too, have created noise in the universe—unnecessary, unhelpful noise—speaking of things I knew not of. I have endeavored lately to pause before speaking—to reflect. Is this true? Does it need to be said? So much noise—so much harm and confusion created by speaking incorrectly, unnecessarily.”

The young woman’s entry in the lean-to register then concludes: “The rain has dropped off. The wind is up.”

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on May 11, 2018