Cruger’s Folly

Proverbial wisdom has it that each of us is the architect of our own fortune. We build our houses and dwell therein, sleeping in the beds we have made for ourselves. Yet who among us is without an ample share of folly? Who isn’t jonesing for a conspicuous McMansion on a height?

“Folly” nowadays is properly understood as the pursuit of foolishness, but in former times the word was used to refer to any costly building or structure designed merely for decoration. For instance, the wealthy in 18th century France and England were fond of constructing “fake ruins” on their estates. A stroll through their elaborate gardens led one to phony Egyptian pyramids and phony Roman temples and phony Chinese pagodas. All this phoniness was intended to evoke in the visitor a sense of the “picturesque,” as if you were ambling around in a pretty painting. Think of such follies as precursors to today’s virtual reality arcades.

In any case, the aesthetic promise of this sort of landscape feature was not lost upon the artists and gentry in America. Writing in 1836, the painter Thomas Cole—after noting the dearth of  cultural attractions in his home region—observed: “The Rhine has its castled crags, its vine-clad hills, and ancient villages; the Hudson has its wooded mountains, its rugged precipices, its green undulating shores—a natural majesty, and an unbounded capacity for improvement by art. Its shores are not besprinkled with venerated ruins, or the palaces of princes; but there are flourishing towns, and neat villas, and the hand of taste has already been at work. Without any great stretch of the imagination we may anticipate the time when the ample waters shall reflect temple, and tower, and dome, in every variety of picturesqueness and magnificence.” Cole didn’t have long to wait for his desired “improvement by art.”

cultural attractions in his home region—observed: “The Rhine has its castled crags, its vine-clad hills, and ancient villages; the Hudson has its wooded mountains, its rugged precipices, its green undulating shores—a natural majesty, and an unbounded capacity for improvement by art. Its shores are not besprinkled with venerated ruins, or the palaces of princes; but there are flourishing towns, and neat villas, and the hand of taste has already been at work. Without any great stretch of the imagination we may anticipate the time when the ample waters shall reflect temple, and tower, and dome, in every variety of picturesqueness and magnificence.” Cole didn’t have long to wait for his desired “improvement by art.”

At that time, John Church Cruger was a young lawyer from a respected family with a long American lineage. According to an obituary writer for the New York Times, “His tastes soon led him to renounce the prospect of success at the bar and devote himself to the life of a country gentleman.” In 1835 he purchased an island in the Hudson River, renamed it after himself, and proceeded to build a mansion. In those days, no estate along the Hudson was considered complete unless it included a tastefully designed folly. Cruger was enchanted by Thomas Cole’s 1834 painting Moonlight and modelled his folly after it, fabricating a ruined church out of local fieldstone and situating it atop a rocky prominence on the southern end of his island. There it stood, dramatically visible to all passing trains and steamships.

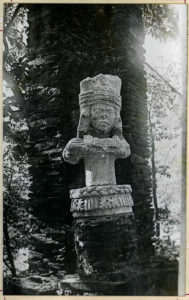

The pièce de résistance for Cruger’s Folly arrived in 1842—via steamship from Yucatán. On board was a large number of ancient Mayan stone carvings, gifted to him by his friend, the bestselling author-explorer John Lloyd Stephens. The carved stones were among hundreds of other exquisite artifacts “obtained” by Stephens and his colleague Frederick Catherwood (himself an artist and antiquarian) and intended to serve as the basis for a new American Museum of Antiquities. As one historian describes it: “The collection was painstakingly carried out of the jungle on the backs of natives. Particularly the valuable carved wood, vases, and idols had to be handled with great care.” These more delicate objects made it safely to New York and were installed in a panoramic exhibition—only to be destroyed shortly thereafter when the museum went up in flames. The only treasures from Central America that escaped destruction were the carved stones that Stephens had pried loose from the walls of the ancient city of Uxmal—they had been delayed in shipping and did not arrive until after the fire. Having nowhere to house them, Stephens gave his stones to Cruger for installation in his folly. There they “took up their ancient vigil” and served “as strange a use as any relics that were ever rescued from the jungle.” For his part, Cruger enjoyed taking guests—who included Washington Irving and Thomas Cole—on moonlit boat rides around the island in order to show off his installation piece to best advantage. Cruger’s Folly quickly became one of the most notable landmarks on the river.

The pièce de résistance for Cruger’s Folly arrived in 1842—via steamship from Yucatán. On board was a large number of ancient Mayan stone carvings, gifted to him by his friend, the bestselling author-explorer John Lloyd Stephens. The carved stones were among hundreds of other exquisite artifacts “obtained” by Stephens and his colleague Frederick Catherwood (himself an artist and antiquarian) and intended to serve as the basis for a new American Museum of Antiquities. As one historian describes it: “The collection was painstakingly carried out of the jungle on the backs of natives. Particularly the valuable carved wood, vases, and idols had to be handled with great care.” These more delicate objects made it safely to New York and were installed in a panoramic exhibition—only to be destroyed shortly thereafter when the museum went up in flames. The only treasures from Central America that escaped destruction were the carved stones that Stephens had pried loose from the walls of the ancient city of Uxmal—they had been delayed in shipping and did not arrive until after the fire. Having nowhere to house them, Stephens gave his stones to Cruger for installation in his folly. There they “took up their ancient vigil” and served “as strange a use as any relics that were ever rescued from the jungle.” For his part, Cruger enjoyed taking guests—who included Washington Irving and Thomas Cole—on moonlit boat rides around the island in order to show off his installation piece to best advantage. Cruger’s Folly quickly became one of the most notable landmarks on the river.

And so the Mayan carvings kept their “ancient vigil” in that phony ruin of a church—until 1919, when the American Museum of Natural History purchased the wayward antiquities from Cornelia Cruger, last surviving child of John Church Cruger. At that point, she was in her eighties and still living on the island, though in a reduced financial state. Her father’s now-ruinous mansion was falling down around her. She gladly accepted the accepted the 18,000 dollars offered for the Stephens Stones, which were promptly removed from the folly and shipped to New York. After Cornelia’s death in 1922, Cruger’s Island was bought by a man who made his wealth from bread and cake. Presumably he pursued his own follies, though no record of them is available. In 1960, the island came into the possession of a utility company that planned to build a large nuclear powerplant on the site. Before they could follow through with this folly, an accident at Three Mile Island took the wind out of their sails. Three years later, the State of New York acquired Cruger’s Island—along with the surrounding bays—and designated it as a wildlife management area. It remains so to this day.

Presumably he pursued his own follies, though no record of them is available. In 1960, the island came into the possession of a utility company that planned to build a large nuclear powerplant on the site. Before they could follow through with this folly, an accident at Three Mile Island took the wind out of their sails. Three years later, the State of New York acquired Cruger’s Island—along with the surrounding bays—and designated it as a wildlife management area. It remains so to this day.

Little trace of previous folly can be found on Cruger’s Island. Venture out there today and you will be halted in your tracks by formidable signage affixed to trees: “Restricted Area: All Trespass in this Area is Prohibited from January 1 through September 30.” Human beings are forbidden to enter this “Endangered Species Critical Area”—at least most of the time. Apparently that’s when eagles have their dalliances and raise their young. But who cares? There’s nothing to see here. The island is pockmarked with the holes of artifact looters and overrun with poison ivy and crawling with ticks. If it’s Mayan carvings you seek, then hop on a train and head down to the city, where they are still on display at the museum.

Here on the island it’s another story, one told by heaps of stone and a few scattered bricks—the only vestiges of Cruger’s Folly, a fake ruin whose fortune it was to become real.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on April 20, 2018