Thomas Cole’s Last Mountain

The artist Thomas Cole died at home in the village of Catskill on February 11, 1848. He had just turned forty-seven years old. Even by 19th-century standards, this seems young. Consider, for example, Cole’s wife, Maria, who lived to be seventy-one; or his boon companion, the poet William Cullen Bryant, who survived to age eighty-three; or fellow Hudson River School painter Asher B. Durand, who made it all the way to ninety. Cole’s early demise is all the more notable given how much exercise the fellow enjoyed. His good friend and biographer, Louis Legrand Noble, recounts how Cole was in the habit of making strenuous excursions “through the cloves, and up to the peaks of the mountains, for the gathering of thoughts, and the kindling of his feelings, as

well as for making fresh studies.” The very last of Cole’s inveterate mountain jaunts took place over two days in October, 1847.

As recounted by Noble, who probably accompanied him on this final hike, Cole “went to the top of the huge precipice, on the side of South Peak, a point visible from his house at a distance of some twenty miles and commanding a wonderful prospect.” Indeed, many today would claim that the view from this peak is the finest in all the Catskills. When seen from a distance, South Peak is one of the most prominent features on the landscape. Anybody who has driven north along the NY State Thruway approaching Kingston is familiar with its outline. “Like a corner stone,” writes Cole’s student Charles Lanman, South Peak “stands at the junction of the northern and western ranges of the Catskills, and as its huge form looms up against the evening sky, it inspires one with awe, as if it were the ruler of the world.” On that October day, the mountain forest was aglow with the same autumn colors that characterize so many of Cole’s landscape paintings. The artist-mountaineer made a long and arduous bushwhack up through a steep and tangled ravine, arriving at last at the precipice. “From this dizzy crag,” writes the biographer, “Cole took a long and silent look up and down the beloved valley of the Hudson.” Then he made a short descent to a “small, glassy pool, bordered with moss, and roofed with the gay foliage of the month,” where he ate his lunch, “his final mountain repast.” Four months later the artist would be dead, having succumbed to a sudden attack of pleurisy.

Cole discovered South Peak’s superior alpine allure only late in life. Most of his backcountry explorations in the Catskills were conducted in the vicinity of the Pine Orchard, Kaaterskill Clove, and the prominences today known as High Peak and Roundtop. He had made one previous ascent of South Peak—just a year before—with a party of eleven others, including his wife. Cole devoted several pages in his journal to recording this trip, concluding with these words: “I shall never forget the quiet sorrow with which, in the course of the forenoon, we bade farewell to South Peak, and slowly took our way down the mountain. . . .” South Peak, though lately imbedded in the artist’s imagination, never did find its way onto one of his canvases.

To mark the 170th anniversary of Cole’s death, I made a winter ascent—along with some friends—of South Peak. They were unfamiliar with the name. The trailhead parking lot that morning was empty—surprising, given that this is one of the most frequently climbed peaks in the Catskills. Or maybe not so surprising on this particular day. The temperature was bitter, the parking lot glazed with thick ice. A foot of snow lay in the woods. Louring clouds threatened to add more. A few intrepid souls with snowshoes the day before had punched out a passable way to proceed up the old mountain road leading to South Peak’s summit, two and a half miles distant. Our progress was slow and grueling, the snow deepening with the gain of elevation. We trudged past the expansive ruins of a bygone mountain hotel. We gazed up at the blinking, buzzing confusion of a modish communications tower, comprehending none of the messages. We circumvented a formidable metal gate across the road and ignored a rusty “Stop” sign. At last we arrived at the top of South Peak, which since the early 1950s has been crowned with a sixty-foot lookout tower. On this day it was veiled in dense, frigid clouds. No view was to be had and it was too cold to stop and eat our lunch. We gave up on any idea of a mountain repast and instead made a hasty descent whence we came.

If you’ve stayed with me to this point and you’re at all familiar with the Catskill Mountains, you must be saying: “Wait a minute! I’ve never heard of any South Peak. This mountain you’re describing sounds a lot like Overlook!” And you would be right. As I noted in a previous column, names assigned to mountains—especially here in the Catskills—become shape-shifters over time. Up through the mid-19th century, “South Peak” was the most common—but certainly not the

only—appellation for this particular landform. Other names in use included “South Point,” “Woodstock Point,” and “Woodstock Mountain.” Likely as not, most of the inhabitants who lived in its shadow had no name for it other than “the mountain.” These days almost everybody calls it “Overlook Mountain.” That’s how it’s labeled on all the maps. That’s what the official sign at the trailhead says. And—who knows?—maybe the mountain itself prefers this cognomen.

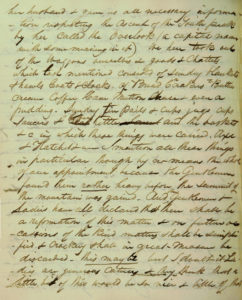

In any case, Thomas Cole seemed to have an intuition of where things were headed. On his first trip to South Peak in 1846, he and his party drew their wagons to a halt in front of a farm at the base of the mountain. In his journal, Cole writes: “W.W. Daniels & his sons & wife were making hay in the meadow below.” The artist waved to them. Mrs. Daniels took a break from the family labors and came over, barefooted, to greet the recreationists. In short order, she provided them with “all necessary information respecting the ascent of the South Peak, by her called the Overlook.” Cole liked the sound of it. He remarked: “Overlook” is “a capital name with some meaning in it.”

And there you have it: Overlook, South Peak, Woodstock Mountain, or your own. What more could be hoped for in the bestowing of any name, but that it might have some meaning in it?

©John P. O’Grady

(This piece originally appeared in the February 16, 2018 edition of The Mountain Eagle.)