Artist Graveyards

Not long ago, I made a trip down the mountain and across the river to Columbia County to visit historic Hudson City Cemetery. I was looking for the grave of Sanford Robinson Gifford, who died in 1880 at the age of fifty-seven. Gifford is one of the few artists associated with the Hudson River School who was actually from the region. His good friend and fellow artist Jervis McEntee was also from around here, having been born and raised in Rondout. McEntee was a pall-bearer at Gifford’s funeral and helped place him in the grave. The plot is located on the steep, morning-side slope of Academy Hill, which these days is crowned by a humdrum development of condominiums—locally referred to as “Vinyl Village”—and a sizable water treatment plant. After Gifford’s funeral, which took place on the last day of August, the mourners adjourned to the family’s home, where dinner was served. At 6 p.m., McEntee took his leave. As he made his way south toward Kingston, the loss of his dear friend—combined with that of McEntee’s wife two years earlier—weighed heavily upon him. “As I came home in the twilight,” he writes in his diary, “I looked at the beautiful mountains where we had been so much together and which glorify so many of his canvases and felt how henceforth they would be sacred ground to me in memory of him and dear Gertrude.”

As for the sacred ground of Hudson City Cemetery, its origins lay in the Rural Cemetery Movement of the mid-19th century. By 1820, the most populous cities in the United States were facing a  “burial crisis.” In the rapidly growing urban centers of the still-new republic, citizens couldn’t care less about the dead. As noted by one observer in 1831: “The burying-place continues to be the most neglected spot in all the region, distinguished from other fields only by its leaning stones and the meanness of its enclosure, without a tree or shrub to take from it the air of utter desolation.” The crowded burial grounds had become noisome boneyards of disregard, not to mention public health hazards. The typical funeral took place—as reported by a Scottish traveler in 1828—at a “soppy churchyard, where the mourners sink ankle deep in a rank and offensive mould, mixed with broken bones and fragments of coffins.”

“burial crisis.” In the rapidly growing urban centers of the still-new republic, citizens couldn’t care less about the dead. As noted by one observer in 1831: “The burying-place continues to be the most neglected spot in all the region, distinguished from other fields only by its leaning stones and the meanness of its enclosure, without a tree or shrub to take from it the air of utter desolation.” The crowded burial grounds had become noisome boneyards of disregard, not to mention public health hazards. The typical funeral took place—as reported by a Scottish traveler in 1828—at a “soppy churchyard, where the mourners sink ankle deep in a rank and offensive mould, mixed with broken bones and fragments of coffins.”

Reformers in Boston sought to address this unwholesome situation by designing an extensive, park-like burying ground to be constructed on the outskirts of the city. They designated this kind of development as a “rural cemetery.” There visitors could enjoy passage along smoothly graded roadways through an undulating landscape of shade trees, birdsong, and picturesque ponds, all the while gazing upon tasteful funerary monuments inscribed with consoling words. With any luck, visitors would depart from this newfangled necropolis a little less disconsolate than when they entered. This first rural cemetery was dedicated in 1831 and was called Mount Auburn. Over the next few decades, many other cities—large and small, all across America—followed suit, establishing their own rural cemeteries, including the City of Hudson.

In addition to providing pleasant surroundings for proper repose of the dead, the new rural cemeteries instilled in the living a sense of having roots in a particular place, of possessing a “perpetual home” for the memory of the dearly departed. In 1855, a proponent of rural cemeteries effused: “The spot where their fathers and their friends are buried, if it possess those charms which impress the heart and gratify the taste, will never be forgotten, and the land which contains it, though it have no other attraction, will yet be dear to the living for this.”

But of course, fashions change: as in apparel, so in burial grounds. By the end of the 19th century, rural cemeteries had faded in popularity, superseded by so-called lawn cemeteries and the convenience of cremation. Add to this the vicissitudes of the economy and the extinction of family lines, and it’s no wonder so many rural cemeteries fell into neglect and disrepair. Hudson City Cemetery did not escape these ravages of time. In 2011, an assessment of the gravestones there revealed many were badly damaged and either partially or wholly unreadable. In the Gifford family plot, all but two of the twenty-two monuments were tipped over. One of them—that belonging to Gifford’s father—was cracked and needed repair. Through the efforts of gallery owner Peter Jung and others, money was secured to bring in a stone mason to repair, clean, and re-set the stones. When I visited the Gifford family plot on a warm July afternoon, it did indeed “possess those charms which impress the heart and gratify the taste.” As for the rest of Hudson City Cemetery, some might say that it needs a good bit of TLC, but I find myself in agreement with Peter Jung, who describes the place as being “in a wonderful state of disrepair” with “a mood and a vibe that would be lost if everything was perfect.”

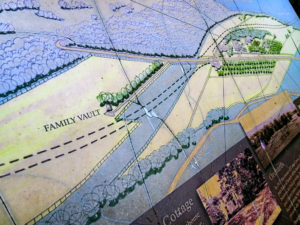

As I was driving home from my visit to the cemetery, I stopped to fill up at a convenience store just on the other side of the Rip Van Winkle Bridge in Catskill, close by to Cedar Lawn, home of the artist Thomas Cole. Today his house is a National Historic Site. You can almost see it as you’re pumping gas. I say “his” house but really it belonged to the family of his wife, Maria Bartow, whose grandfather—Dr. Thomas Thomson—established there a modest “gentleman’s farm,” which at its greatest extent included 155 acres along the crest of the hill, where the views were “lovely with rounded hills, little bits of the village peeping out here and there from behind clustering foliage, and scattered groups of old apple trees.” In 1818, the Thomson family acquired a 35-acre parcel just to the northwest of the house, where in 1821 they built a family burial vault. Cole himself was so enchanted by this secluded site with its extraordinary view of the Catskill escarpment that he wrote a poem:

To be sepulchered here—to rest upon

The spot of earth that living I have lov’d

Where yon far mountains steep; would constant look

Upon the grave of one who lov’d to gaze on them.

Thomas Cole got his wish. When he died in 1848, his remains were interred in the sanctified peace and quiet of the Thomson family vault.

His final rest, sad to say, was not so final. Ten years after his death, the family sold off some land, perhaps in order to make ends meet. The sale included the parcel upon which the Thomson vault stood. Cole’s remains—along with those of the other family members in the tomb—were removed and re-interred down the street at the Catskill Village Cemetery. There they have rested ever since. Those “yon far mountains” still look upon that very “spot of earth” where, for a short while, the painter Thomas Cole was “sepulchered.” Today the restive living gaze back on the fabled range, as they fill their insatiate vehicles with gas.

©John P. O’Grady

Originally appeared in The Mountain Eagle on August 3, 2018